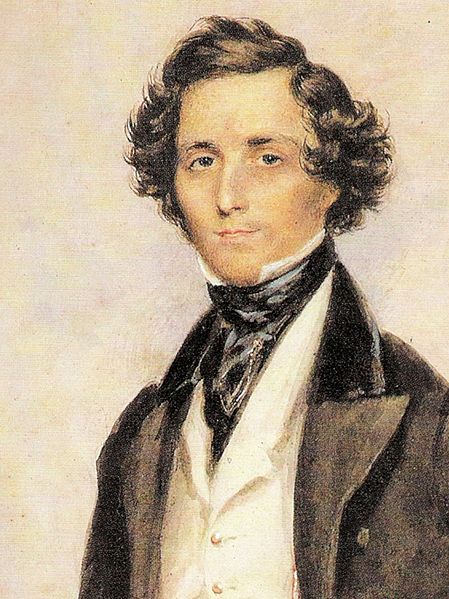

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847) carved out a niche for himself not only as a composer but also as a conductor and pianist, a feat few of his contemporaries would match.

A child protege, he made his debut as a pianist in 1818 and composed his first symphony for full orchestra when he was 15. In 1829, he arranged and conducted a performance of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion, thereby playing an integral role in reviving his music.

One of the finest composers of the Romantic era, Mendelssohn was incredibly prolific and versatile. He wrote more than 700 compositions — symphonies, concertos, piano and violin pieces, chamber music, oratorios and songs.

In short, he ranks as one of the most accomplished musicians ever produced by Germany.

Born in Hamburg, he died in the eastern city of Leipzig, where a museum, the only one of its kind, commemorates his extraordinary life. It marks its 20th anniversary this year.

Close to the Gewandhaus concert hall, of which he was music director, Mendelssohn Haus is located inside a 19th century building which served as his last residence. He and his family lived there from 1845 until his death at the age of 38. He was buried in the Trinity Cemetery in Berlin.

As I wandered through the building — which was constructed in 1843, refurbished in the 1870s and transformed into a museum in 1997 — the precious objects associated with Mendelssohn came into view: Furniture, including an upholstered sofa and matching five chairs. A grand piano he practised on. Original sheets of music. A lock of his hair under glass.

In addition to these items, I saw workmanlike oil portraits of Mendelssohn and watercolors of idyllic Swiss scenery he painted himself.

The son of a Jewish banker and the grandson of the Enlightenment philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, he lived in this house with his French wife, Cecile Jeanrenaud, and their four children, Karl, Marie, Paul and Felix. After Mendelssohn’s death, his family left and the building was converted into a paint factory. In 1867, a sheet music publisher rented the first floor. A decade later, a merchant bought the building.

From the 1920s onward, it was filled with commercial offices, boarding rooms and a photography lab. In 1991, a year after East and West Germany were reunified, Kurt Masur, the 11th music director of the Gewandhaus, founded an association to perpetuate Mendelssohn’s legacy. By then, his stock had been in decline for decades, undermined by changing musical tastes and antisemitism.

Though born Jewish, Mendelssohn and his three siblings were baptized as Christians in 1816, following their father’s decision to renounce Judaism and change the family’s surname to Bartholdy. Like Heinrich Heine, the great German-Jewish poet, Mendelssohn’s father believed that Christianity would be his and his children’s “admission ticket” to acceptance as Germans.

Although Mendelssohn achieved fame during his lifetime, having composed such timeless pieces as the Italian Symphony, the Wedding March, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Songs Without Words, his acceptability as a German was archly questioned by some Germans.

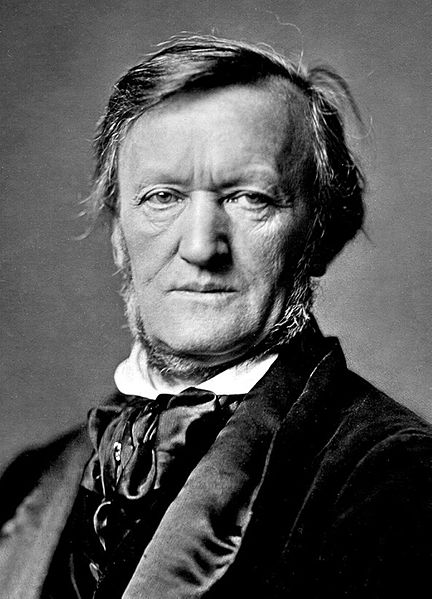

Mendelssohn’s jealous rival, Richard Wagner, wrote a scurrilous pamphlet, Jewishness in Music, in which he accused Jews of being a foreign and harmful element in German culture. Foreshadowing Nazi propaganda, Wagner claimed that Jewish composers could only produce shallow works because they had no real organic connection to Germany.

By no coincidence, Adolf Hitler was an admirer of Wagner. During the Nazi period, Mendelssohn’s compositions were accordingly banished from the public domain and his statue in front of the Gewandhaus was demolished, prompting the resignation of Leipzig’s mayor.

As Nazi antisemitism intensified, several of Mendelssohn’s descendants, all Christians, were forced to leave the country. Still others, like the Prussian aristocrat Jurgen von Schwerin, whose grandfather was a Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, were untouched. Today, the descendants of Felix and his brother, Paul, live in Berlin under different names.

Jurgen Ernst, the director of Mendelssohn Haus, said that antisemitism was only one factor in the decline of Mendelssohn’s reputation. “At the end of the 19th century, Romanticism went out of style,” he explained. “Schumann was affected by this development, too. Yet Mendelssohn was not forgotten, especially in Britain.”

The Mendelssohn renaissance was promoted by Masur, who believed he had been unjustly relegated to the margins. In short order, he created the Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy Foundation to save his last residence from further decay and to raise funds for a thorough renovation. Ernst, an engineer and stage craftsman who had been employed by the Leipzig Opera, was hired as a fundraiser. He convinced private donors, as well as municipal and state governments, to contribute to the project.

Mendelssohn Haus, with its modest gardens shaded by chestnut trees, was officially inaugurated in 1997, on the 150th anniversary of Mendelssohn’s death. Since then, tens of thousands of tourists have visited to learn more about this musical genius.