The first genocide of the 20th century occurred not in Europe but in South West Africa (now Namibia), a colony that Germany had annexed in the early 1880s. Now, a debate has emerged regarding the genocide and its meaning within German 20th-century history, particularly the extent to which it can be seen as a precursor to Nazi crimes.

Most people know that Belgium, France, Britainand Portugal controlled massive empires in Africa from the late 19th century until the 1960s. Less well known is the fact that Germany, though a latecomer to colonialism, also managed to acquire a number of African possessions, but lost them all after its defeat in World War I.

Its colonies included what are now Burundi, Cameroun, Namibia, Rwanda, Tanganyika and Togo.

Germany came late to the scramble for colonial territory. But many Germans viewed colonial acquisitions as a true indication of having achieved nationhood, and demanded their so-called “place in the sun.” So Germany joined other European powers in the so-called “scramble for Africa,” and in fact hosted the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, which carved up the continent.

Rebellions in the newly-acquired German colonies when they took place were brutally crushed.

The uprising in South West Africa by the Herero people, known as the Maji-Maji rebellion, in retaliation against land seizures by German colonists, began in 1904. The Nama people joined the uprising in 1905.

As a result, between 1904 and 1908, as many as 80 percent of the Herero, believed to number around 100,000 a century ago, perished, either killed by German soldiers or left to die of thirst and starvation in the desert. Some 20,000 members of the Nama tribe were also murdered.

Lothar von Trotha, the German commander in Namibia, in an infamous “extermination order,” declared that “every Herero, with or without rifles, with or without cattle, will be shot.” Dozens were beheaded after their deaths, their skulls sent to researchers in Germany for discredited “scientific” experiments that purported to prove the racial superiority of white Europeans.

By 1908, as David Olusoga and Casper Erichsen write in The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism, only 16,000 Hereros and 10,000 Namas were left alive. “Our understanding of what Nazism was and where its underlying ideas and philosophies came from,” they contend, “is perhaps incomplete unless we explore what happened in Africa under Kaiser Wilhelm II.”

Germany has rightly concentrated its critical energies on the Holocaust, according to German historian Jurgen Zimmerer. “But that has also meant that there has been much less awareness of the crimes of colonialism.”

Zimmerer, a professor of history at the University of Hamburg, in his book From Windhoek to Asuschwitz: On the Relationship Between Colonialism and the Holocaust, examines the relationship between colonialism and the Holocaust. He situates Nazi crimes firmly within the global history of mass violence.

The German colonial wars against the Herero and Nama represent, he argues, a “decisive link to the crimes of the Nazis” and were an “important source of ideas” for Germany’s war of annihilation in Eastern Europe after 1939.

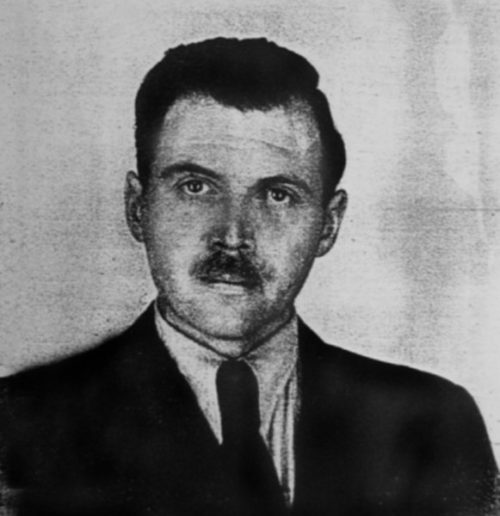

One scientist who studied race in South West Africa was Josef Mengele, the doctor who conducted experiments on Jews in Auschwitz. Heinrich Goering, the father of Hermann Goering, Adolf Hitler’s commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe, was the colony’s first governor.

The most influential interpretation of the connections between the era of imperialism and Nazism was actually offered decades ago in Hannah Arendt’s masterpiece, The Origins of Totalitarianism, published in 1951.

According to Arendt, European imperialism served as a laboratory of racial doctrines and anonymous bureaucratic policies that were based on “decrees” rather than the rule of law.

This past August, skulls and other remains of massacred people used in colonial-era experiments were handed over by Germany to Namibia at a church ceremony in Berlin.

Michelle Muentefering, a minister of state for international cultural policies in the German foreign ministry, asked “for forgiveness from the bottom of my heart” to Namibia’s culture minister, Katrina Hanse-Himarwa.

Negotiations are now focusing on how Germany will compensate and apologize to Namibia.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island