Germany tried but failed to conquer the British mainland during World War II, but German forces nevertheless occupied a small bit of Britain, the Channel Islands. Lying closer to France than Britain, these predominately rural islands, near the coast of Normandy, were captured by the Germans on June 30, 1940 and held until May 9, 1945.

Madeline Bunting, in the newest paperback edition of The Model Occupation: The Channel Islands Under German Rule 1940-1945 (Vintage), skilfully recounts this intriguing footnote of World War II.

Adolf Hitler hoped that Germany’s presence in the Channel Islands would be a model of Anglo-German cooperation, a testing ground for the eventual German occupation of Britain. As Bunting says, the islanders would learn that there was no such thing as a model occupation under the Nazis. Nonetheless, they more or less accommodated themselves to it, fraternizing and collaborating with the Germans until the very end and thereby blemishing Britain’s record of standing up to Nazism.

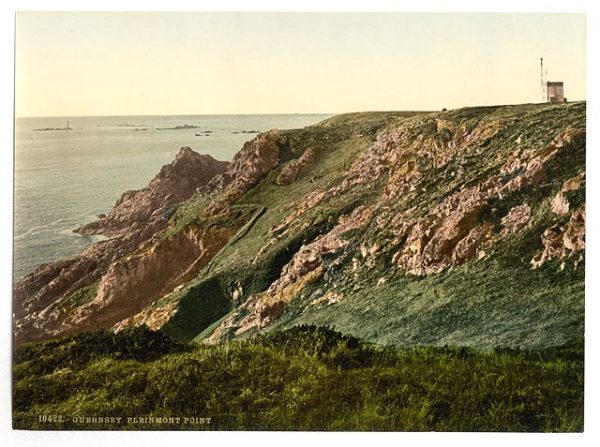

Washed by clear turquoise seas, the pastoral Channel Islands, notably Jersey, Guernsey, Sark and Alderney, were famous for their semi-tropical climate, beautiful beaches, stunning cliffs and early crops of tomatoes, potatoes, flowers and grapes. Seventy miles from Britain, the islands, 76 square miles in size, were a family holiday destination for many Britons before the outbreak of the war in 1939.

Deemed a non-strategic asset by the British government, they were demilitarized and stripped of their military garrison following Germany’s invasion of France. Confident that Hitler had no interest in capturing the islands, Britain neglected to inform Germany of its decision. Nonetheless, thousands of islanders left, leaving the islands with a population of approximately 60,000.

On a sleepy Sunday morning, the Germans landed in Guernsey. On the days to follow, they wrested control of the remaining islands. Ambrose Sherwill, the islands’ chief administrator, complied with all German orders. “The Germans were delighted, the invasion had gone off without a hitch,” writes Bunting, the first edition of whose book was published in 1995. “Contrary to German expectations, the invaders had been greeted with polite deference by the conquered subjects of a proud nation.”

To the Germans, this was to be a model occupation. “The cordial relations between the German commander and the island authorities were to be matched by the polite helpfulness of the islanders and the law-abiding soldiers. It quickly became apparent that there was no need for the troops to carry a pistol or wear a steel helmet.”

After the fierce fighting in Poland, Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, the islands seemed like a holiday camp to the German occupiers. “They were enchanted by the islands’ little coves, the steep cliffs covered with wildflowers and the bright blue sea.” Initially, the usually reserved islanders kept their distance of the Germans, but ultimately, they established “correct relations” and formed contacts, friendships and romantic liaisons with them. In some cases, these relationships caused rifts in families.

Senior German officers, many of whom spoke excellent English, made a point of being polite and respectful to members of the island government. The “iron hand in a velvet glove” policy, which had been recommended by a German historian who visited the islands in 1941, was officially adopted by Germany.

Shocked by the occupation, Britain launched a series of ineffective pinprick raids to recapture the islands. These attacks emboldened the Germans to beef up their garrison. By mid-1942, 37,000 German troops were stationed on the islands, many billeted with local families, the majority of which were employed by the Germans.

As time went on, the Germans tightened their grip on the islands. German language lessons were made compulsory for school children over the age of 10 in 1942. In the same year, males between 16 to 70 who had not been born on the islands or had permanent residency permits were deported.

The long arm of Nazi antisemitism reached the islands in the autumn of 1940, when upwards of 20 Jews, including a handful of Jewish refugees, lived there. Notices were published instructing all those with Jewish grandparents who “belonged to the Jewish religion” to present themselves for registration at the islands’ Aliens Office. Twelve people showed up.

About six months later, the identity cards of Jews were stamped with a capital J in red. In further anti-Jewish measures, Jewish businesses were confiscated without compensation and Jews were forbidden from holding jobs, owning radios or entering shops or public buildings. In three instances, Jews were deported to Nazi extermination camps in Poland.

Island officials complied with German orders, none considering “the welfare of a handful of Jews sufficiently important to jeopardize good relations with the Germans,” says Bunting. “A mixture of ignorance, indifference and antisemitism all contributed to these British officials playing their tiny part in the tragedy of the Holocaust.” In her view, the “Jewish issue” was the most clear-cut example of where island cooperation with the Germans “tipped into outright collaboration.”

As Bunting correctly observes, the mistreatment of Jews on the islands challenged the facile assumption that British civil servants and police would not have cooperated with the Germans in sending Jews to the gas chambers had they invaded Britain.

In 1943, a group of 800 French Jews, all married to Christians, was brought to the islands. “Instead of being sent to the gas chambers, they were detailed to work as slave laborers,” she says. “They counted themselves the lucky ones. A few food parcels managed to get through to them from their families, and few of them died.”

From 1941 to 1944, about 16,000 foreign workers were sent to the islands to build fortifications and roads. Many of them were treated harshly. “The presence of thousands of emaciated foreign workers was painful evidence of Nazi brutality,” writes Bunting. “It drove home the islanders’ awareness of their own vulnerability and the fact that their well-being depended on the fragile goodwill of the Germans.”

Certainly, Hitler had no interest in alienating the locals, contending that the islands were a “laboratory” for Anglo-German relations. He hoped that the islands would be a German colony after the war and assumed they could be a valuable submarine base for the German navy.

After the war, the British government launched an investigation to ascertain whether islanders had collaborated with the Germans. No cases were ever brought to trial, nor were any Germans tried for their wartime activities. Instead, one island official was knighted and still others were the recipients of honors. “This was an outcome unique among the countries which had been occupied,” says Bunting.

In short, Britain’s attitude toward the islanders was “forgive and forget.”

Collaborators were left to be punished by social ostracism. Those who could not bear the strain left, resettling in Britain or immigrating to New Zealand and South Africa.