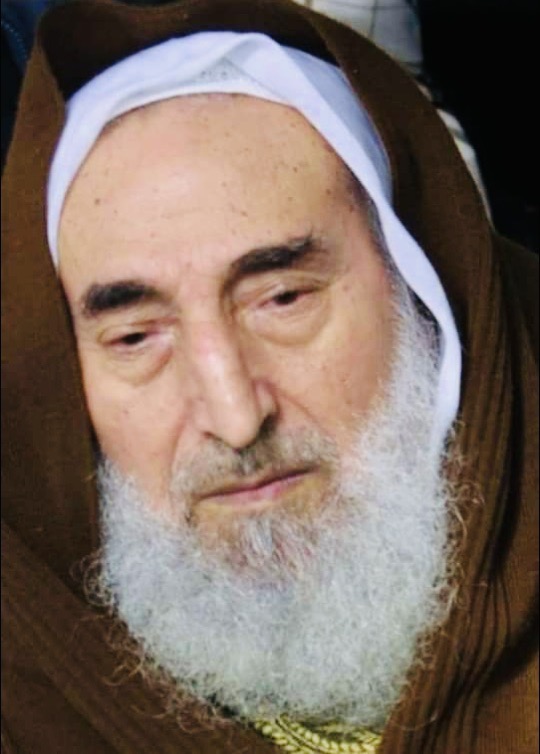

Hamas, the Islamic movement that has been embroiled in fierce combat with Israel in the Gaza Strip since the slaughter of 1,200 Israelis and foreigners on October 7, was founded by Sheikh Ahmad Yassin 36 years ago this month during the opening days of the first Palestinian uprising.

Its status as an important component of the Palestinian struggle against Israel is ably chronicled by Tareq Baconi in Hamas Contained: The Rise and Pacification of Palestinian Resistance (Stanford University Press). Although this book was published in 2018 and has been somewhat overtaken by recent events, it is well worth reading even today because it is thorough and comprehensive in scale and scope.

Baconi, the president of the Al-Shabaka Palestinian Policy Network and the book review editor of the Journal of Palestine Studies, has a firm grasp of his subject and conveys its complexity in lucid prose.

Being a Palestinian Arab himself, he writes from a Palestinian perspective. Yet he takes a relatively balanced approach, criticizing Hamas here and there. And he is eerily prescient, saying that “another conflagration” between Hamas and Israel is imminent, and predicting that “the manner in which the next war unfolds will be event-specific.”

Little did he know just how right he would be.

Five years after the publication of Hamas Contained, a plethora of kibbutzim and army bases in southern Israel were ruthlessly attacked by scores of Hamas terrorist bands intent on wreaking death and destruction on a nation that, inexcusably and tragically, had let down its guard in a colossal intelligence and military failure.

Describing Hamas as “the movement currently most representative of the notion of armed resistance against Israel,” he also compares it to “a religious and armed anti-colonial resistance movement.” At another point, he quotes Hamas political leader Ismail Haniyeh as saying, “We are a people who value death, just as our enemies value life.”

Interestingly enough, Baconi is “unwavering” in his condemnation of targeting civilians on either side of the Israeli/Palestinian divide. Yet he rejects the common assumption that Hamas is a terrorist group, and concurs with the view that “Palestinian resistance fighters” are engaged in “a justified war” against Israel, which, he admits, is “a superb foe.”

He agrees that Gaza, comprising merely 1.3 percent of the lands of historic Palestine, has been a thorn in Israel’s side since its creation as a Jewish state 75 years ago. To many Israelis, Gaza is little more than a terrorist haven, an “enemy-ridden enclave” weighed down by poverty and misery. Since 1948, Israel has waged a succession of battles and wars in Gaza and occupied and reoccupied it.

And now, as these words are written, Israel is engaged in an existential war with Hamas and its sister organizations that may well transform the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East.

Originally known as The Islamic Faction and the Path of Islam, Hamas was established by Yassin and his colleagues as the first intifada broke out in December 1987. A teacher and an imam from southern Palestine, he joined the Muslim Brotherhood in the 1950s. Yassin was an admirer of its Egyptian founder, Hassan el-Banna, and of Izz al–Din al-Qassam, a fiery preacher and Palestinian nationalist who was killed by British colonial police in 1936 and after whom Hamas’ armed wing is named.

In 1976, Yassin successfully applied to the Israeli occupation authorities for a licence to establish the Islamic Association, which would provide social, religious, educational and medical services to its constituents. As Baconi points out, Israel green lighted the project to weaken secular Palestinian groups such as the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Yassin’s focus on Islamization at the expense of resistance to Israel’s occupation created “significant resentment” in Palestinian circles. Consequently, a splinter group, Islamic Jihad, defected in 1981 to confront Israel. In the meantime, however, Yassin and his associates were secretly stockpiling weapons in anticipation of a rebellion.

Officially launched in January 1988 as the Islamic Resistance Movement, Hamas issued its first charter several months later in which it called for the formation of an Islamic state in all of historic Palestine. Baconi concedes that Hamas’ covenant was replete with antisemitic references. As it was unveiled, the PLO, its competitor, transitioned into a diplomatic track focused on achieving Palestinian statehood in 22 percent of Palestine.

Since then, as Baconi says, Hamas has abided by three fixed principles: a refusal to relinquish Palestinian land and a twin commitment to resistance and the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes in what is now Israel.

During the first Palestinian uprising, Hamas carried out terrorist attacks, leading Israel to brand it as a terrorist organization and to arrest Yasssin, who was given a lifetime sentence, plus 15 years, in jail. In the wake of his imprisonment, Hamas developed its military capabilities through the establishment of the Izz-al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, which are now battling Israeli forces in Gaza. Iran, of course, played a pivotal role in this development.

Hamas turned to suicide bombings as a tactic after an American Jewish settler, Baruch Goldstein, killed 29 Palestinian worshippers in a mosque in Hebron in 1994. Its first such bombing, in Afula, killed seven Israelis. Hamas’ suicide vests were created by Yahyah Ayyash, whom Israel would subsequently assassinate. Due to these attacks, Hamas became “the central instigator of armed operations against Israel.” Hamas, too, was a fierce opponent of the 1993 Oslo peace process.

Hamas justified “martyrdom” operations on the false presumption that the entire Israeli population was “militarized.” It erroneously believed that it would ultimately achieve deterrence and compel Israel to withdraw from the occupied areas. In fact, Israel doubled down on its determination to crush Palestinian resistance. Furthermore, Hamas’ suicide bombing campaign turned Israelis further to the right and prompted them to elect Benjamin Netanyahu of the right-wing Likud Party as prime minister in 1996.

At the same time, Gaza became “the model space for the Palestinian struggle” against Israel. Baconi contends that Israel’s guerrilla war with Hezbollah in southern Lebanon emboldened Hamas to conclude that armed resistance was the only way to “liberate Palestine.” Its hardline policy forced Yasser Arafat, the president of the Palestinian Authority, to crack down on Hamas, at least sporadically, and compelled Israel to assassinate Hamas’ leadership from Yassin on down.

Hamas supposedly accepted the notion of Palestinian statehood within the boundaries of Gaza and the West Bank, but this was nothing more than a case of smoke and mirrors. Hamas did not relinquish its goal of “liberating” Palestine. Nor was Hamas prepared to recognize Israel, reject violence or accept agreements between Israel and the Palestnian Authority. No wonder Israel ignored Hamas’ bogus shift toward peace.

With the eruption of the second Palestinian rebellion in 2000, Hamas developed a rocket capability, firing its first such projectiles on April 1, 2001. Hamas also built an elaborate network of tunnels from the Sinai Peninsula to smuggle basic supplies, weapons and munitions into Gaza. By 2008, more than 500 tunnels snaked beneath the Rafah border crossing, bringing in a monthly revenue of about $36 million to Hamas.

Baconi argues that the second intifada, plus Israel’s unilateral pullout from Gaza in 2005, burnished Hamas’ political credentials. Certainly, its victory over Fatah in the 2006 legislative election in Gaza was a turning point, though the idea of armed struggle did not figure prominently in its electoral platform. He believes that Hamas won a plurality of seats in the legislative council due to corruption in Fatah ranks, resentment at failed peace talks with Israel, and Hamas’ reliability in providing welfare services to an impoverished population.

With its coup in 2007, Hamas gained full control over Gaza, crushing all opposition to its dictatorial rule and creating what Baconi describes as a “totalitarian order.”

Israel and Egypt proceeded to impose a land, sea and air blockade of Gaza, quashing freedom of movement in and out of Gaza and cutting Gaza off from the West Bank.

Within a month of Hamas’ takeover, new tensions swelled as Hamas and Islamic Jihad launched rockets at Israeli towns and cities, Israel responded with air raids and ground incursions, and the Israeli government labelled Gaza as a “hostile territory.”

Shortly afterward, the wars of 2008, 2012 and 2014 broke out and ended with fleeting ceasefires that eventually collapsed. Baconi lists the wars in detail, correctly pointing out that Israel failed to deter Hamas or Islamic Jihad when it “mowed the lawn” in each war.

During this turbulent period, Israel acquiesced to Hamas’ rule in its attempt to contain Hamas and stabilize Gaza. For its part, Hamas opportunistically accepted “the need to pacify the resistance front in the short term” in order to survive. “This allowed Hamas to sustain its resistance legacy even when, in practice, it did police armed struggle,” he writes.

Baconi acknowledges that, while many Palestinians reject Hamas’ rhetoric, ideological intransigence and action on the ground, they laud Hamas for conveying the fundamentals of Palestinian demands and identity from 1948 onwards. “Hamas believes that the only language of dialogue with Israel is one of violence between occupier and occupied,” he goes on to say.

As of 2017, Hamas was contained in Gaza against its will, but it continued to build and strengthen its military arsenal while it awaited an opportune moment to strike Israel. That moment, of course, occurred on October 7.

Peering into the future, Baconi ponders the possibility of an Israeli invasion of Gaza to depose Hamas. “Defeating Hamas militarily would, obviously, be one way of ridding Israel of its Hamas problem. But that would simply transport Hamas’ ideological drivers to another vehicle that would remain rooted in the key tenants of the Palestinian struggle.”

Israel should bear this in mind as it armed forces push deeper into Gaza in a concerted campaign to eradicate Hamas as its governing authority.