My father, David Kirshner, does not appreciate publicity, though he is increasingly fond of talking about his past as a soldier in the Polish army and a Holocaust survivor who endured the rigors of the Lodz ghetto and the horror of Auschwitz extermination camp.

I realize that this short essay may upset or anger him. But just this once, I`ll ignore his aversion to seeing his name in print. David, you see, turned 100 on April 10, and I thought that this special milestone would be worthy of at least a little notice.

David, or Duvid, as he was known in Yiddish, was born in 1914, nearly four months before World War I erupted and four years before Poland achieved its independence after centuries of Russian, Austrian and Prussian domination. He was born in Lodz, a city in central Poland whose textile mills were an integral component of the Polish economy.

His parents were from the working-class and enjoyed few of the amenities of modernity. They lived simply, like the vast majority of Jews in Poland, and conveniences we take for granted in Canada, like running hot water, a shiny new car, a vacation on a palm-fringed tropical island and bananas and oranges even in the dead of winter, were way beyond their means or vision.

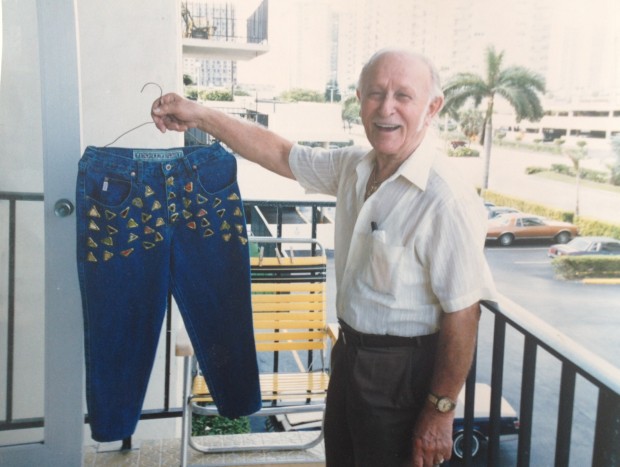

David never aspîred to study at university. Even if he had been driven by that ambition, he would have discovered that precious few Jewish students could gain admission to universities in Poland. David came of age in an era when open antisemitism was a fact of life in Poland, as it was elsewhere in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. So like many Polish Jews, he went into the crafts. He became a tailor, mastering his trade as Europe lurched closer to another continent-wide war.

Before Poland was engulfed in conflict, David was conscripted into the Polish army. He was posted to Poznan, a lovely town in western Poland that had once been part of Germany. When hostilities broke out on Sept. 1, 1939, David was called up to defend his country. He was wounded and captured on the battlefield and treated for his wounds in Germany. He was sent back to Lodz in 1940, when Poland was already occupied by two great antagonistic powers, Germany and Russia (known then as the Soviet Union).

For the next four years, David was a fireman in the Lodz ghetto, whose workshops turned out goods for Germany. Thousands of Jews died of starvation and disease, and many more thousands were deported to Nazi death camps, during that nightmarish interregnum.

I`ll probably never know with any degree of certainty why David survived while others perished. But I guess he survived because the ghetto needed fireman and because, in the final analysis, he was a consummate survivor whose sense of self-preservation enabled him to surmount every conceivable challenge and threat.

David was concerned not only with himself. His younger sister, Helen, told me a chilling story to illustrate his loyalty to family. The Germans were rounding up yet more Jews, and David, having gotten wind of this looming raid, saved his two sisters and parents by concealing them in a basement. To this day, Helen says she owes her life to him.

The Lodz ghetto was liquidated in August 1944, the last ghetto in Nazi-occupied Europe to be dismantled. David and his wife-to-be, Genya, were transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. My mother lost a son, a brother I never knew, in Auschwitz. But somehow or other, they survived. In the last weeks and months of the war, they were sent to different camps, and there, too, they managed to overcome the odds stacked against them.

My parents, who had known each other prior to the war, rekindled their friendship in a displaced persons camp in southern Germany, a district controlled by the American army. I was born near that camp, in a clinic in Bad Reichenhall, a spa in the foothills of the Bavarian Alps. David and Genya could have gone to Palestine, like scores of Holocaust survivors, but ended up in Canada due to a shortage of garment workers in the Canadian clothing industry, centred in Montreal.

After a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean, we landed in Halifax. From there, a train took us to Montreal. My father, a skilled craftsman, had no trouble finding a job. Stein & Gerson, a ladies’ wear manufacturer in downtown Montreal, hired him shortly after our arrival in the winter of 1948. This is where he worked for the next 20 years. We lived in a succession of flats around St. Lawrence Blvd, near majestic Mt. Royal.

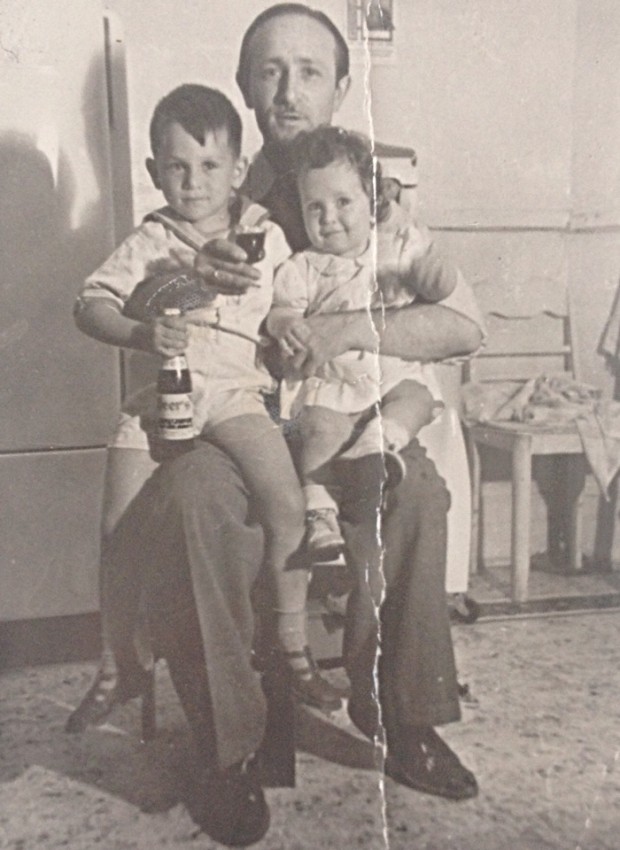

My sister, Marilyn, was born in 1949. My youngest sister, Shirley, was born five years later, after my parents had bought their first home, a duplex, on Dunford Place, close to Decarie Blvd. In 1957, they moved upward, purchasing a new duplex on Bedford Road. The builder, Lou Zablow, was a Polish survivor himself.

My father was a hard worker and toiled five and a half days a week. My mother was a classic home maker, taking care of everything else. Before leaving for work each morning, he’d make his own sandwiches, larding the bread with thick layers of butter. He was and still is a fussy eater. He likes bread, soups of all kind, herring, pickles, pickled brine, potatoes, onions, cheese and noodles, but little else. He definitely does not care for chicken or beef, which was always a source of disappointment to my mother.

In the early years, we spent summers in rented cottages in the Laurentian mountains, north of Montreal. On Friday evening, after the sun had set, he would typically arrive by train and trudge up a hill to meet us. Those were the days.

My father bought his first car in 1958, a year before my bar mitzvah. It was a used Chevrolet or Oldsmobile with oversize fins. He was proud when I learned how to drive and earned my driver’s licence. In admiring tones, he called me a “driver engineer.” My father never really acquired fluency in English. He spoke a broken, accented English, like all the “greeners” from the old country.

He lost his coveted job in 1968, when Stein & Gerson declared bankruptcy. By then, we were living in a beautiful duplex on Lockwood Ave., in the predominantly Jewish suburb of Cote St. Luc, where many Holocaust survivors, like our neighbors, the Srebrniks, lived. He got by with freelance jobs. My mother supplemented our income by working in a bakery owned by Mr. Eisenberg, a Holocaust survivor.

They purchased Friendly Tailors & Valet Service, a dry cleaner on St. Mark Street, shortly afterwards. My father and mother worked together at making it a success, and they fared reasonably well. Late in 1969, my father was shot resisting a holdup. He almost died. I found out about it six months later. I was in Britain, completing an MA, when the disaster struck. My mother didn’t want to interrupt my studies, so she remained silent.

When I returned from London in the summer of 1970, my father seemed like a completely different man. He was quiet and withdrawn, no longer outgoing and gregarious.

It took him several years to recover, but his purchase of a red, late-model Chevrolet in September of that year raised his spirits. He adored this car and washed and polished it to a high sheen every week, and his dedication to it prompted neighbours to call him Sterling Moskowitz. My father also sought relief from this tragedy in Sunny Isles, Florida, where he and my mother spent many winters in their condo.

I did not see enough of my parents from 1971 until 1981, when desire brought me to Israel, where I married Etti, and necessity took me to Toronto, where we started a new life. Since Marilyn and I lived in Toronto, my parents decided to join us, leaving Shirley and her husband in Montreal, at least for a while. In Toronto, my father worked for a rental tuxedo company, but finally he retired for good.

In retirement, he battled adversity. Cancer. The removal of a kidney. A hip replacement. A pacemaker implant. Yet as before, he persevered and turned survival into a virtue and an example to be emulated.

Despite these setbacks, he never lost his zest for living — taking great pleasure in attending war veterans’ meetings, participating in their marches, showing off his array of medals, boisterously holding forth as he recalled his days as a soldier and his brushes with death during the Holocaust, enjoying the company of his children and his grandchildren, downing my mother’s hearty soups, stopping strangers in the Promenade Mall for animated bits and pieces of conversation and taking summer holidays in the Catskills.

My father has reached the ripe old age of 100, and he’s still going strong, despite his frailty of body. Genya, his wife of nearly 70 years, is near his side and keeps him company, as does the rest of the family and his caregivers.

He needs a walker to keep him steady on his feet, but his mind is clear and sharp, and he loves telling stories.

He lives life to the fullest, like a much younger person, and revels in it.

Happy birthday, tato, man of the century.