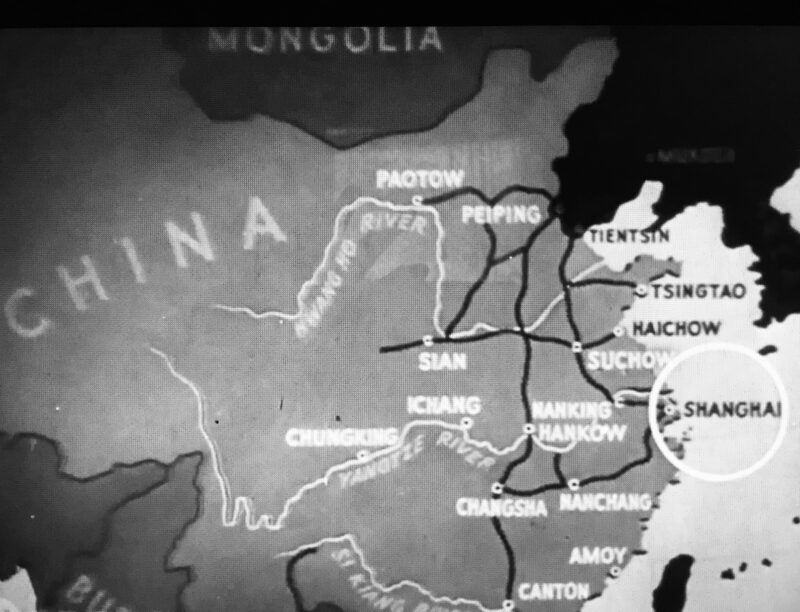

To the European Jewish refugees who found a temporary haven in Shanghai during the late 1930s and early 1940s, China’s biggest port was as faraway as any metropolis in the Far East could be. Vibrant, chaotic, dirty and cosmopolitan, Shanghai was a destination of last resort for upwards of 20,000 German, Austrian, Czech and Polish Jews fleeing antisemitic oppression.

But never in their wildest dreams could they have imagined that this throbbing city would be there for them in their greatest hour of need, as one of the refugees observes in Violet Du Feng’s absorbing documentary, Harbor From The Holocaust, which will be broadcast by the PBS network on Tuesday, September 8 from 10 p.m. to 11 p.m. (check local listings).

Jews seeking safety from fascist persecution, particularly after Kristallnacht in Germany in 1938, were faced with the bitter realization that their chances of obtaining foreign visas were slim due to antisemitism and xenophobia. Democracies like the United States, Canada and Britain would only accept a limited number of Jewish refugees. Nor were Latin American nations keen to welcome them. Cuba, for example, turned away a boatful of German Jews on the St. Louis, forcing the downcast passengers to return to Europe.

Shanghai, however, was different.

It was the only place where Jews were allowed in without restrictions. This was the case because it was not ruled by one central authority. Shanghai had been partitioned into extraterritorial enclaves by several countries during the late 19th century. And in 1937, it was captured by Japan, an imperial power whose tentacles would soon envelop Asia.

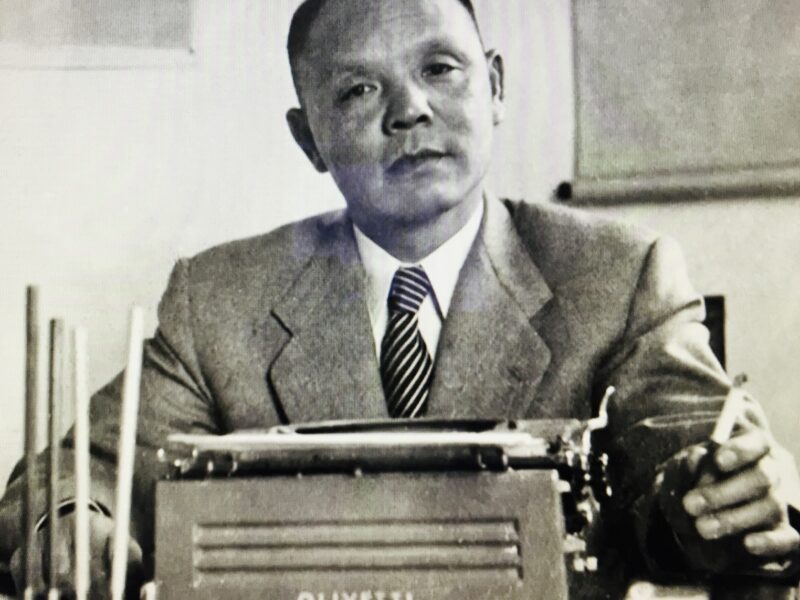

Consequently, refugees could enter Shanghai without formalities. But at least several hundred Jews arrived with Chinese visas issued by China’s consul-general in Vienna, Ho Feng Shan, who sympathized with their plight after witnessing the Nazi persecution of Austrian Jews.

Shan’s daughter, Manli Ho, an American citizen, and several of the refugees interviewed in this nearly one-hour film, recall his humanitarian work. In the main, the refugees talk about their experiences in Shanghai, where the contrast between the rich and the poor was extremely striking and disheartening.

When they arrived, Shanghai was already home to an established Jewish community of Baghdadi (Middle Eastern) and Russian Jews. Victor Sassoon and Horace Kadoorie, two of the Baghdadi elders, were helpful in providing the newcomers with services ranging from housing and food to education and protection.

The refugees also pay tribute to Laura Margolis, an official from the American Joint Distribution Committee who established soup kitchens in Shanghai.

Not surprisingly, they experienced downward mobility in Shanghai. Middle-class families accustomed to the finer things in life were thrown into poverty, having been compelled to leave their assets and possessions behind when they left their homes.

Michael Blumenthal, a German Jew who would serve in President Jimmy Carter’s cabinet, remembers the bedbugs, mosquitos and rats in the fleabag hotel he and his parents shared at the outset.

But there was a silver lining, the refugees agree. Chinese people accepted them and showed compassion.

Although Japan was politically aligned with Nazi Germany, Japanese administrators in Shanghai treated them fairly decently. Indeed, they rejected a proposal by a Nazi emissary, Joseph Meininger, to place the refugees abroad leaky vessels in the hope they would drown.

But after Japan’s attack on the U.S. naval fleet at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japan herded foreigners into internment camps. And in February of 1943, the refugees were forced live in Hongkou, a destitute and congested neighborhood.

While a lot of them compared themselves to shipwrecked castaways who had been washed ashore on a distant island, they made themselves at home by opening European-style restaurants and cafes and establishing German-language newspapers and theatres.

Their children learned English at a school expressly built by Kadoorie. Their fluency in English would be very useful later on in their lives in North America and elsewhere.

On July 17, 1945, a U.S. bombing raid aimed at a Japanese radio station in Hongku accidentally killed some refugees. Less than a month later, the war in the Pacific ended, prompting the refugees to leave Shanghai.

As a footnote in World War II, the Shanghai interregnum was surely one of the most exotic, judging by Harbor From The Holocaust.