Nearly 60 years after his suicide, the American novelist, short story writer and journalist Ernest Hemingway is still a formidable, even legendary, figure. Hemingway, a three-part PBS biopic by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, explores his life and legacy through forceful words and evocative photographs and newsreels.

This absorbing documentary, narrated by the actor Peter Coyote, is enhanced by commentary from literary critics and writers. Mary Dearborn, the author of the latest Hemingway biography, offers insights as well, as does one of his three sons, Patrick.

Portrayed as the most celebrated American writer since Mark Twain, he is seen as a path-breaking novelist who changed the English language with his terse, declarative and deceptively simple style.

By the age of 30, he was the most famous writer in the United States, having published two critically acclaimed collections of short stories, In Our Time and Men Without Women, and two blockbuster novels, The Sun Also Rises and A Farewell To Arms.

Oozing masculinity, he revelled in the great outdoors, loving deep-sea fishing in Cuba and big-game hunting in Africa. Drawn to Spain, he was an admirer of bullfighting and a supporter of the loyalist cause during the Spanish Civil War.

Fuelled by copious amounts of alcohol, he was a lover of women, having been married no less than four times. A complicated man, he was congenial and generous, yet cruel and vengeful, and prone to depression and paranoia.

Born in 1899 in Oak Park, a sylvan suburb of Chicago, he was the second of six children. His father, a doctor, instilled in him a primal feeling for nature. As he grew older, his admiration for him dimmed. Hemingway’s relationship with his mother was contentious, possibly because they were both opinionated and judgmental.

Tremendously disciplined, he started writing in his junior high school year. Thanks to an uncle, he landed a reporting job on The Kansas City Star, whose style manual stressed the importance of simplicity. He covered crime and labor disputes.

In 1918, during the dying months of World War I, he joined the Red Cross as an ambulance driver on the Italian front, where he was wounded. Convalescing in a field hospital, he fell in love with an American nurse. Returning home in 1919, he wrote war stories, all of which were rejected. The Toronto Daily Star, however, accepted some of his freelance pieces.

Hemingway’s first wife, Elizabeth Hadley Richardson, not only gave him the self-confidence to pursue his passion for writing, but bought him his first typewriter, an elegant-looking Corona. Hemingway’s mentor, the novelist Sherwood Anderson, was impressed by his “extraordinary talent” and convinced him to live in Paris, where he would spend several formative years. It was there that he met, among others, the poet Ezra Pound and the American poet, novelist and art collector Gertrude Stein.

From his base in Paris, Hemingway travelled around Europe, contributing features and news stories to The Toronto Daily Star and its sister publication, The Star Weekly. In 1923, he was hired by the Star as a staff reporter, but disliking his editor and his assignments, he soon quit. By 1924, he was back in Paris, focusing on creative writing. One of his short stories, Up in Michigan, was praised by the critic Edmund Wilson.

Within a period of two months in Spain, he composed his first novel, The Sun Also Rises. One of its characters, Robert Cohn, was modelled after his Jewish friend Harold Loeb. Convinced he had a brilliant future, F. Scott Fitzgerald, the up-and-coming novelist, recommended Hemingway to his editor, Maxwell Perkins. Hemingway’s next collection of short stories, Men Without Women, garnered mixed reviews, but one of its pieces, Hills Like White Elephants, was regarded as masterful.

Now remarried to Pauline Pfeiffer, who selflessly devoted herself to him, Hemingway wrote his second novel, A Farewell To Arms, which was based on his wartime experiences. A dogged craftsman, he supposedly wrote 47 versions of the last few paragraphs.

Continually restless, he hewed to certain routines. Ensconced in his new home in Key West, Florida, he would begin writing at first light and would not stop until about noon. A constant traveller and adventurer, he went fishing in Cuba, touring in Spain and hunting in Africa.

It took him five years to finish his next novel, Death in the Afternoon, and while he thought it was his best work, some critics disagreed. It was followed by Green Hills of Africa, published in 1935. During this period, he wrote one of his finest short stories, The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

Left-wing critics, though, panned him as a dilettante. Taking their critique to heart, he dashed off To Have and Have Not, his prototype of a proletariat novel. Critics disliked it and so did he.

Hemingway appreciated the dangers posed by the rise of fascism in Europe, but was essentially an isolationist opposed to U.S. involvement in European affairs. With the eruption of the civil war in Spain, he modified his view.

Having signed a contract with the North American Newspaper Alliance to file stories from Spain, Hemingway covered the conflict there. By now, he had split from Pfeiffer and was having an affair with the half-Jewish reporter Martha Gellhorn, whom he would marry and with whom he would have a tempestuous relationship.

His newest novel, For Whom the Bell Tolls, which was set in Spain, was praised by The New York Times as his finest one yet. A roaring commercial success, it sold five million copies in six months. He wrote it in Finca Vigia, a restored hilltop villa near Havana that he and Gellhorn had purchased.

During the early part of World War II, Hemingway lived much of the time in Cuba, writing and fishing and entertaining an assortment of visitors. In May 1944, Collier’s magazine sent him to Europe to report on the impending allied invasion of Europe. He was based in London, where he would meet his fourth wife, the foreign correspondent Mary Welsh.

He went back to Cuba in the spring of 1945, depressed by the sights he had witnessed during the war. He drowned his sorrow in the balm of alcohol.To add to his depressive mood, his writing was not going well. His new novel, Across the River and Into the Trees, was the object of barbs from critics. Suffering from delusional spells, he confessed he was fed up with living and he contemplated suicide.

Inspired by his infatuation with a young Italian woman he had met recently, Hemingway produced one of his most accomplished novels, The Old Man and the Sea, which impressed the majority of reviewers and was bought by five million readers.

In 1954, Hemingway and his wife survived two planes crashes in Africa on successive days. Newspapers reported his death in front page headlines he must have read with bemusement.

In the wake of these near-death experiences, he grew increasingly abusive and short-tempered. “He just lost all restraint,” says his son Patrick, with whom he severed relations. “We never saw each other again.” Sadly, Hemingway was also estranged from his youngest son, Gregory, a cross dresser who had gotten into trouble with the police.

As his physical and mental health declined, Hemingway’s career reached a crescendo of acclaim with his selection as the winner of the Nobel Prize for literature.

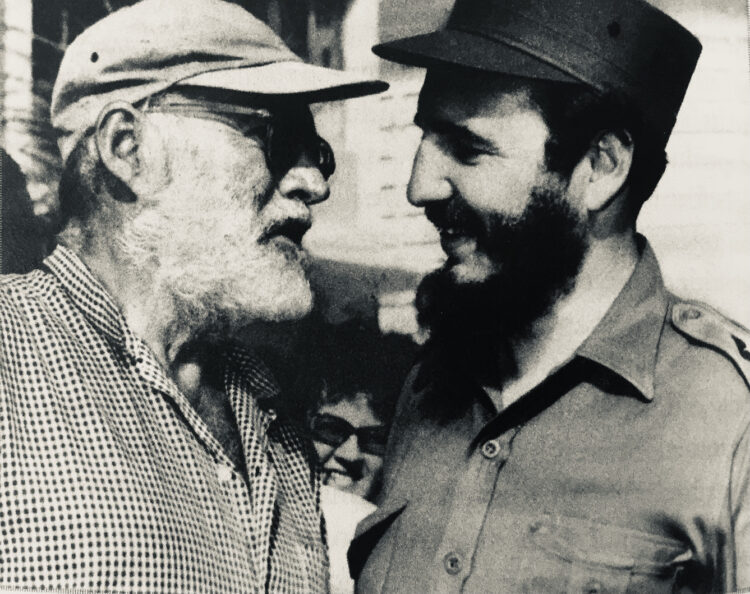

Hemingway sympathized with the 1959 Cuban revolution. In 1960, he was photographed in the company of Cuba’s leader, Fidel Castro. When the United States broke diplomatic ties with Cuba shortly afterwards, Hemingway was unable to return to his beloved villa, causing him further distress.

Diagnosed with psychotic depression, he submitted to electric shock treatment, which deprived him of his short-term memory. Fearing he could no longer write, he sank deeper into the slough of despair. On July 2, 1961, at his new home in Ketchum, Idaho, he fatally shot himself in the head with a rifle, leaving this vale of tears in exactly the same manner as his father. He was three weeks shy of his 62nd birthday.

He left behind unpublished manuscripts, which were published posthumously. Islands in the Stream, a novel, was the object of faint praise. A Moveable Feast, an atmospheric memoir of his Paris interregnum, was widely perceived as his final masterpiece.

Hemingway had lived life to the fullest.