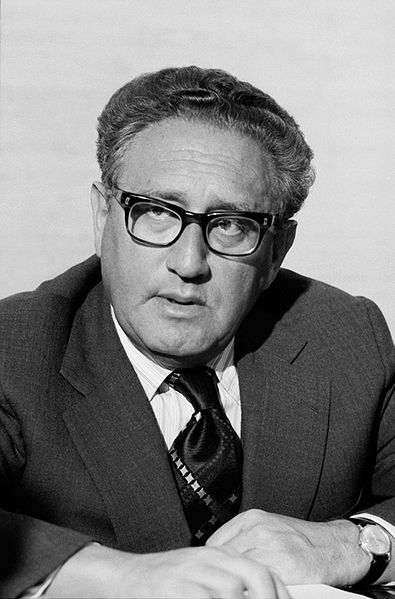

Henry Kissinger had a finger in virtually every pie when he was U.S. secretary of state, managing the foreign affairs file of the world’s preeminent superpower.

“There cannot be a crisis next week,” he once joked in a sardonic moment of levity. “My schedule is already full.”

Kissinger was indeed a busy bee.

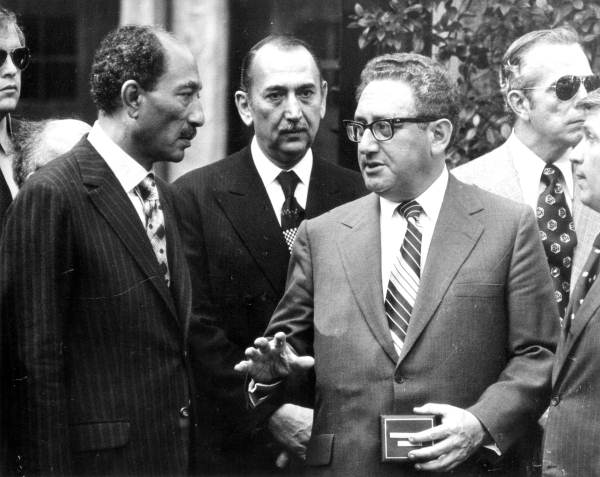

He negotiated the end of the Yom Kippur War, his shuttle diplomacy paving the way for the Camp David accords and Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt. He prepared the ground for the renewal of diplomatic relations between the United States and China, a turning point in the annals of the Cold War. He ratified the Helsinki Final Act, which theoretically forced the Soviet Union, among other countries, to respect human rights and fundamental freedoms.

And the list goes on.

The first Jewish American and the first foreign-born citizen to be appointed secretary of state, Kissinger loomed large. As an indication of his impact on world events, he appeared on the cover of Time magazine no fewer than 15 times while in office from 1973 to 1977.

Yet Kissinger, a master of realpolitik, was reviled in some circles as a diplomat who placed more importance on stability than morality. Some critics even claimed that he was the inspiration of Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove. Niall Ferguson, his biographer, thinks otherwise. “Far from being a Machiavellian realist, Kissinger was in fact from the outset of his career an idealist,” he writes in Kissinger (Penguin Press), the first of two volumes exploring his life.

Describing him as a “Kantian idealist,” Ferguson — a professor of history at Harvard University — claims that Kissinger sought to identify the United States with, rather than against, the post-colonial revolutions following World War II. But Kissinger understood there was a clear conflict between two moral imperatives in foreign policy — the obligation to defend freedom and the necessity for coexisting with adversaries.

In this weighty volume –which ends on the eve of his appointment in 1969 as Richard Nixon’s national security advisor — Ferguson takes a reader on an extended journey from Furth, his hometown in Germany, to the United States, where Kissinger and his family landed as refugees fleeing antisemitic oppression.

Ferguson, previously a lecturer at Oxford University, met Kissinger in London at a party hosted by Canadian newspaper publisher Conrad Black. Kissinger asked Ferguson whether he’d be interested in writing his biography. Initially, he declined the offer. But after learning he would have access to 20 boxes of Kissinger’s private correspondence, he perked up and changed his mind.

Ferguson points out he had full editorial control over the final manuscript. Judging by its cool and balanced tone, one can safely accept this claim at face value. Kissinger is a substantive work of scholarship, covering his youth in Furth, his flight from Nazi Germany, his service in the U.S. army, his student days at Harvard and his ascension as a public intellectual and national security consultant.

Born in 1923, he was the scion of middle class Orthodox Jews. Louis, his father, was a teacher. Paula, his mother, was descended from a line of farmers and cattle dealers. Furth’s Jewish community, the third largest in Bavaria after Munich and Nuremberg, was economically integrated but socially and culturally distinct.

The Nazi takeover of Germany had an almost immediate impact on Kissinger’s father. Within four months of Adolf Hitler’s accession as chancellor in 1933, he was “permanently retired” from his post, leaving the Kissingers in limbo. Since Louis Kissinger was an anti-Zionist, he did not consider Palestine as a refuge. The United States beckoned, and in 1938, the Kissinger clan set sail for New York City.

They did not leave Furth a moment too soon. During Kristallnacht, several months later, the main synagogue was burned down, while the Jewish cemetery and Jewish hospital were vandalized. From November 1941 onwards, nearly every single Jew still remaining in Furth was deported to killing grounds in Latvia and Poland.

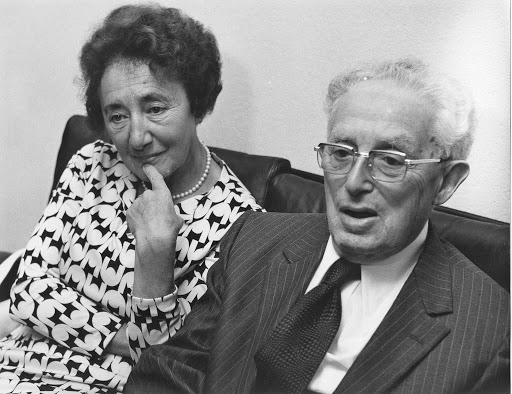

Kissinger denies that Nazi brutality affected his psyche or outlook. Although he has acknowledged he was often chased through the streets of Furth and beaten up by Nazi thugs, he maintains these disruptive incidents left no indelible impression, which is hard to believe. In short, as he said in 2004, his German boyhood meant little to him. Kissinger, however, returned to Furth in 1975 to receive a medal of honorary citizenship. He was accompanied by his parents, who had ambivalent feelings about Germany.

In a colorful turn of phrase, Ferguson writes that the Kissingers arrived in America the year Errol Flynn starred in The Adventures of Robin Hood and Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn co-starred in Bringing up Baby. They rented a flat in Washington Heights, a neighborhood known as the Fourth Reich. Almost one quarter of the nearly 100,000 German Jews who settled in the United States from 1933 onward lived there.

As Ferguson notes, Kissinger adapted quickly to America, but Kissinger senior was plagued by ill health and depression. His mother, meanwhile, became the family’s breadwinner.

Drafted into the army in 1943, Kissinger was posted to a counter-intelligence unit, playing a role in breaking up a Gestapo sleeper cell. He was also present at the momentous Battle of the Bulge, Germany’s last-gasp offensive in 1944 to turn the tide of the war in its favor.

While stationed in Germany, he met Fritz Kraemer, the greatest single influence on him. A German Jewish convert to Christianity who had immigrated to the United States after Hitler’s rise to power, Kraemer was a lawyer and an “orthodox Prussian conservative” whose views shaped Kissinger’s politics.

According to Ferguson, Kissinger came face to face with the Holocaust after visiting the Ahlem concentration camp, eight kilometers west of Hanover. It was one of the most horrifying experiences he would ever have. On a visit to Furth, he discovered that only 37 Jews had survived the Nazi deportations.

After the war, he entered Harvard on a scholarship. Majoring in political science, he was studious, hitting the books from morning till night. In his spare time, he founded Confluence, a journal devoted to contemporary political problems. Among its contributors were the American and French philosophers Hannah Arendt and Raymond Aron.

Kissinger’s doctoral dissertation, deemed the best of 1954, was published in book form. A World Restored: Metternich, Castlereagh and the Problems of Peace, 1812-1822, laid out the principles of balance-of-power diplomacy, which would characterize his own policies.

Much to his disappointment, Harvard declined to hire him as a junior professor. But within a few years, he would be something of a celebrity, an expert on nuclear strategy and a best-selling author. He shot to fame as a strategic thinker on the strength of a controversial essay on preventive nuclear war.

Thanks to a Harvard contact, Kissinger obtained a job at the Council of Foreign Relations. From there, he hopped, skipped and jumped into a tenured professorship at Harvard. By 1958, Ferguson says, he was flying high, wooed by presidential aspirants Nelson Rockefeller and John F. Kennedy.

Ferguson disputes the view that Kissinger supported the war in Vietnam, but it’s a weak argument. “While Kissinger certainly began by thinking … that South Vietnam needed to be defended against Communist aggression, he realized far sooner … that the Kennedy and Johnson administrations were bungling that defence.”

Publicly, he defended Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam policy. “But in private, as the archival records show, he was a scathing critic. Why then did he keep his criticism private? The answer is that Kissinger was not content to carp from the sidelines.”

From 1965 onward, Kissinger made three fact-finding trips to South Vietnam. “What he learned there convinced him that the United States must extricate itself from that country by diplomatic means,” Ferguson writes.

Although claiming not to be a Republican, Kissinger worked for Rockefeller as an outside adviser, regarding him as the only politician who could unite the country.

He had “grave doubts” about Nixon, Rockefeller’s adversary, believing he was “unfit to be president.” Yet Kissinger agreed to be one of his advisers, a decision that would bring him to the White House and alter his life profoundly.

Ferguson will deal with that crowded period in volume two, and I look forward to it.