Nearly eleven years after the eruption of the Second Lebanon War, tensions are rising yet again between two old bitter enemies, Israel and Hezbollah.

In the past few months, as Israel has fortified its border with Lebanon in preparation for a possible fresh round of fighting and bombed weapons convoys destined for Hezbollah warehouses, both sides have raised the spectre of a new war.

Israel’s current assessment is that Hezbollah — an Islamic fundamentalist organization — has no desire at present to embroil itself in a war with Israel as long as a significant proportion of its forces are embroiled in the Syrian civil war in support of President Bashar al-Assad. Hezbollah has lost about 1,000 of its fighters in propping up Assad’s regime and therefore has little or no appetite to confront Israel militarily at this time.

However, Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hezbollah, has reportedly grown weary of and impatient with Israel’s constant air strikes on his arms convoys from Syria to Lebanon. Much to Nasrallah’s anger, Israel has indicated it will continue to target them. As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said recently, “Our policy is very consistent. When we identify attempts to transfer advanced weapons to Hezbollah — when we have the intel and the operational capacity — we act to prevent it. That’s how we’ve acted and how we will continue to act. Everyone needs to take this into account.”

This was the blunt message that Netanyahu conveyed to Russian President Vladimir Putin in Moscow last month. Russia, in league with Hezbollah and Iran, has invested heavily in the effort to help Syria turn the tide in the civil war, which has claimed the lives of more than 400,000 Syrians and left most major cities in Syria in ruins.

Such is the urgency of the issue that Israeli Defence Minister Avigdor Liberman, in talks with U.S. officials in Washington, D.C. in March, portrayed Hezbollah as a major threat to Israel. He told his American interlocutors that the Lebanese army, supplied in part by the United States, may play an active role against Israel in the next war. If true, this would constitute a significant change in its conduct toward Israel. During the 2006 war and the Israeli invasions of Lebanon in 1978 and 1982, Lebanon’s army remained on the sidelines.

Liberman raised the issue following Nasrallah’s announcement in February that Hezbollah would hit specific targets in Israel should another war break out. These include the nuclear reactors in Dimona and Nahal Sorek, weapons factories and an ammonia plant in Haifa, which, if penetrated by enemy missiles, could kill tens of thousands of people, according to Haifa’s mayor, Yona Yahav.

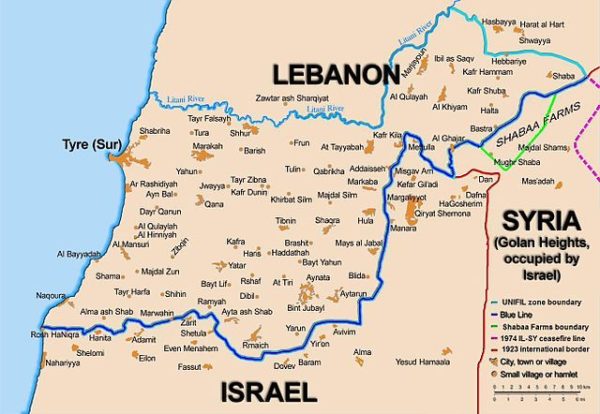

In response to Nasrallah’s threat, General Gadi Eisenkot, the head of the Israeli armed forces, said that Hezbollah continues to “arm and strengthen” itself, and that, contrary to the United Nations resolution that ended the 2006 war, it is operating south of the Litani River, which is relatively close to the Israeli frontier.

Eisenkot warned that Israel would act decisively in the case of new hostilities. He did not elaborate, but Israeli officials have said that the next war will be shorter and more destructive than the previous one. The assumption is that Israel would would try to destroy vital Lebanese infrastructure — roads, bridges, power stations and airports — and Lebanese army bases during the first phase of a war.

This is an important point.

On the first day of the last war, the U.S. secretary of state, Condoleezza Rice, asked the Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, to leave Lebanon’s national infrastructure out of its aerial bombing campaign. The Israeli government more or less abided by Rice’s request, but in retrospect, the restraint Israel displayed may have been a mistake. If Israel had struck its infrastructure harder, Lebanon might well have pressured Hezbollah to stop its daily rocket barrages of Israel. During the course of the month-long war, Hezbollah fired about 4,000 rockets into Israel, causing some property damage, a massive displacement of Israeli civilians and a slowdown of the economy.

Since then, Hezbollah has acquired many more rockets, and Iran, its ally, has built underground rocket factories for Hezbollah throughout Lebanon.

Nasrallah, in his latest speech, predicted that the next war may well be waged inside Israeli territory. As he put it, “Hezbollah soldiers and rockets can reach all the positions across the Zionist entity during any upcoming war.”

And in a dig at Israel, he claimed that the construction of a seven-meter concrete wall along Israel’s border with Lebanon, a project aimed at preventing the infiltration of terrorists into Israeli territory, was a tacit acknowledgement of Israel’s weakness.

Hezbollah spinned an identical argument late last month when it escorted Lebanese journalists on a tour of the border with Israel.

Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri was less than pleased by Hezbollah’s exercise in public relations or psychological warfare. “What happened is something that we, as a government, are not involved with and do not accept,” he said. And in what may be seen as a rejection of Hezbollah’s truculent approach to Israel, he declared he supports a “permanent ceasefire” with Israel.

Tellingly enough, Lebanese President Michel Aoun, who’s closely allied with Hezbollah, has not endorsed Harii’s call for such a ceasefire.