As expected, the mandate of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon was renewed on August 30 for another year. Renewals have not usually posed serious problems because the presence of peacekeepers in southern Lebanon is in everyone’s interest. That’s understood.

This year, however, a potential problem arose. Israel, having complained about Hezbollah’s alarming arms buildup near its northern border, requested that UNIFIL should be invested with new powers to address this troubling issue. As a result of Israel’s demarche and American pressure, the United Nations extended UNIFIL’s mission and embedded this important proviso into its mandate.

From this point forward, UNIFIL will play a more assertive role in helping the Lebanese army patrol the border area. But it remains to be seen whether this will have any effect on Hezbollah, which has become an increasingly powerful player in Lebanese and Middle East politics.

Before the extension was formally approved, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu told UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres in Jerusalem this week that the international body has failed to stop the flow of weaponry to Hezbollah.

Israel’s ambassador to the UN, Danny Danon, said that areas where UNIFIL is deployed should not be “utilized for hostile activities of any kind.” The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, sounded a similar theme. She criticized the commander of UNIFIL, Major General Michael Beary, for downplaying Hezbollah’s arms buildup. “He seems to be the only person in south Lebanon who is blind to what Hezbollah is doing,” she charged. And she asserted that the “status quo” governing UNIFIL’s role was no longer acceptable.

UNIFIL was established in 1978, following Operation Litani. This was Israel’s first invasion of southern Lebanon, which degenerated into a cauldron of violence and instability in the wake of the 1967 the Six Day War. Israel clashed with the Palestine Liberation Organization, which had set up bases there. And in the aftermath of the 1982 war in Lebanon, Hezbollah, supported and armed by Iran, attacked Israeli forces in what would evolve into a costly war of attrition.

In the summer of 2006, Israel and Hezbollah fought a month-long war during which Hezbollah fired some 4,000 rockets against Israel. Under the terms of UN Resolution 1701, the ceasefire that ended the war, all armed groups in Lebanon except the Lebanese army were to be disarmed. At the same time, UNIFIL was expanded, increasing its manpower to 10,500 troops from 41 countries.

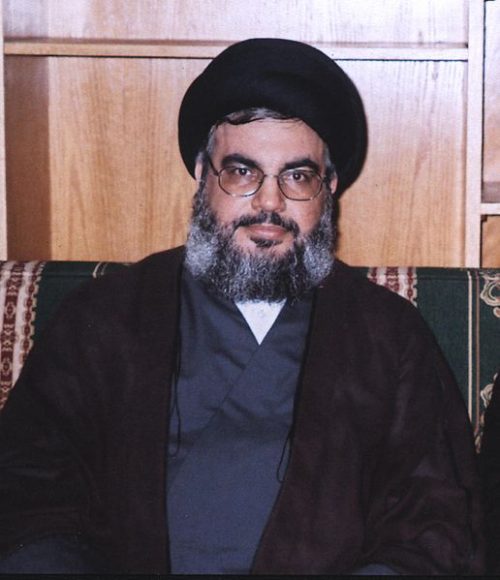

Resolution 1701 was a thorn in the side of Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, who admitted he had miscalculated in goading Israel to launch a war after the kidnapping of two Israeli soldiers in sovereign Israeli territory. He denounced the notion of Hezbollah’s disarmament, saying that the Lebanese army was not strong enough to defend Lebanon and that Israel was still occupying Lebanon. Nasrallah declared that Hezbollah would not be forced to disarm by “intimidation or pressure.”

In the same vein, the then Lebanese defence minister, Elias Murr, said that “the army won’t be deployed to south Lebanon to disarm Hezbollah.”

After the Second Lebanon War, Hezbollah, backed by Iran, embarked on an ambitious program to convert itself into a formidable conventional military force, increasing the number of its fighters from 17,000 to 45,000.

As Yaakov Lappin writes in a monograph published by the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies: “The continuing arms procurement program can be divided into four distinct stages. In 2006-08, Hezbollah focused on restocking its medium and short- range surface-to-surface missiles and rockets. In 2009-12, it concentrated on smuggling long-range surface-to-surface missile/rockets, surface-to- sea missiles, and drones. During the years 2012-16, Hezbollah shifted to receiving precision-guided projectiles, ballistic missiles, and forming commando units for future cross-border raids into Israel. Finally, from 2016 onward, the organization has focused on building up its precision firepower, by both importing such arms and receiving guidance kits for unguided projectiles. It has also been increasing the levels of warheads explosives and is in the process of building its own rocket and missile factories in Lebanon and in areas of Syria under its control.”

According to Lappin, Hezbollah’s weapons are manufactured in Iranian or Syrian factories and are smuggled to Lebanon through different regional routes: “One well-trodden route is the transfer from Iranian factories to Damascus via planes. The final leg of the journey is by ground convoys from Syria to Lebanon. Other routes are possible, such as the hiding of weapons in commercial shipping containers that arrive at Beirut port, or civilian flights landing at Beirut’s international airport …”

Lappin estimates that Hezbollah’s arsenal, consisting of between 120,000 to 140,000 rockets and missiles, is largely composed of short-range rockets with a range of 45 kilometers, as well as thousands of medium-range rockets, and at least several hundred long-range rockets.

Before the 2006 war, he adds, Hezbollah had some 10,000 short- range rockets and under 1,000 medium and long-range rockets, none of which could be described as precision guided.

Today, Hezbollah probably possesses at least dozens of surface-to-surface ballistic missiles, as well as hundreds of drones. It also has hundreds of Fatah-110 guided ballistic missiles with a range of several hundred kilometers.

Israel also believes that Hezbollah likely has advanced air defence batteries, such as the SA-17 surface-to-air missile. If this is the case, says Lappin, Hezbollah may have the ability to disrupt Israeli air activity over Lebanon in the event of another war.

In Lappin’s estimation, Hezbollah probably also possesses dozens of surface-to-sea missiles, including the supersonic Russian-made Yakhont anti-ship cruise missile, which can be fired at not only vessels, but also at offshore gas drilling rigs and all of Israel’s naval bases and ports.

Clearly, Hezbollah is a dangerous adversary.