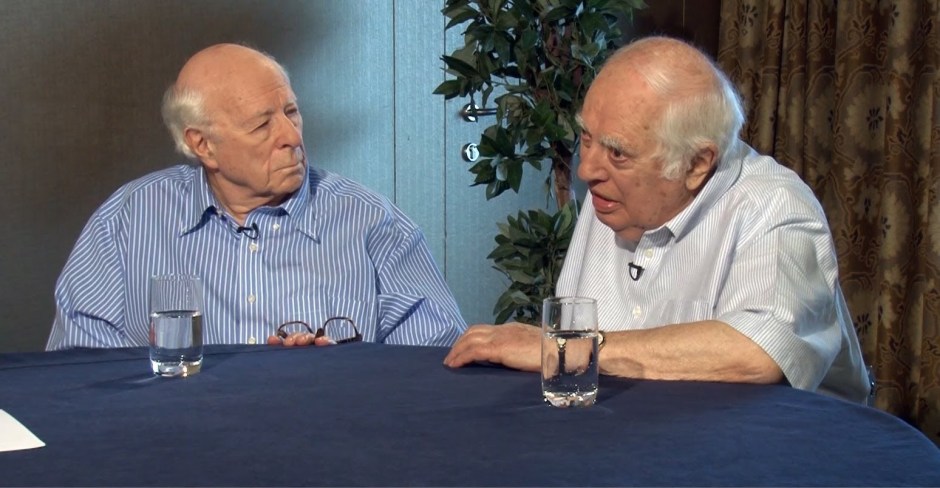

Bernard Lewis, 98, is one of the greatest historians of the Middle East. Formerly a professor of Middle Eastern history at the School of Oriental and African Studies and Princeton University, he has produced a torrent of well-regarded books, from The Arabs in History and The Emergence of Modern Turkey to What Went Wrong? and Islam and the West. Now, in what may be his final work, he has written his memoirs, Notes on a Century: Reflections of a Middle East Historian (Weidenfeld & Nicolson) in cooperation with Buntzie Ellis Churchill.

In this expansive volume, he reflects on his career, events in the region and even his marital woes. As usual, he writes in a flowing, mellifluous style that draws in a reader.

Lewis, who was born in London during the second year of World War I, has been mesmerized by the Middle East since boyhood. “The interest began when I was still a schoolboy. It has grown ever since, becoming first a hobby, then an obsession, finally a profession.”

Initially interested in medieval history, he segued into Ottoman history when the hitherto sealed archives of the Ottoman Empire were opened in 1950. He studied at University College and the School of Oriental and African Studies, both part of the University of London, and learned Arabic after having acquired Hebrew.

In 1937, on the advice of one of his professors, he embarked on his first trip to the Middle East, travelling through Egypt, Lebanon, Palestine and Syria. He returned to Britain to write his first book, The Origins of Ismai’ilism, which came out in 1940.

He began teaching at the School of Oriental and African Studies (from which, incidentally, I graduated). “I was the first professional teacher of Middle Eastern history anywhere in England,” he recalls. “Until then the study and writing of Middle Eastern history … had been undertaken either by historians who knew no Arabic or by Arabists who had a limited understanding of history.”

At the age of 33, he was appointed the first occupant of the newly created chair of the History of the Near and Middle East at the University of London. Given a full year to familiarize himself more closely with the Mideast, he set out for Istanbul in 1949.

Only three countries were wide open to Jewish scholars like Lewis at that time — Turkey, Iran and Israel. Arab nations generally did not issue visas to applicants who listed themselves as Jewish.

In 1955, he spent a year as a visiting professor at the University of California, one of many universities to which he was invited in subsequent years. As he travelled around the United States, he was shocked to discover that “institutionalized antisemitism” was not uncommon in the land of the free.

During his last two years in Britain, he was tormented by a faltering marriage. So much so that he could hardly conduct research and write. In 1974, he turned his life around, arriving in New Jersey to take up a new post at Princeton University. He was not alone, having met an “aristocratic Turkish lady” at a reception at the Iranian embassy in London. He spent the next decade with her. “She restored my faith in life and in myself,” he says.

After an absence of some years, Lewis returned to Egypt in 1969. Upon his return, he wrote a piece under a pseudonym in which he asserted that Egypt was ready for peace and that negotiations could lead to an Israel-Egypt treaty. “That was almost 10 years before it happened,” he writes, patting himself on the back.

Lewis tried to persuade the Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, that the Egyptians were prepared for peace with Israel. But she thought he had been duped. Moshe Dayan, the minister of defence, was less skeptical, but he didn’t want to relinquish the Sinai Peninsula in exchange for peace.

Affinities between Jews and Muslims, he notes, have helped him achieve “a sympathetic understanding” of Islam, the Arab-Israeli conflict notwithstanding. But Lewis is not naive, observing that antisemitism in the Arab world has grown in the past century and a half.

The rise of radical Islam, as exemplified by the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 in the United States, does not surprise him. “As the militants saw it, they had completed the first phase on the path toward Muslim domination — the expulsion of the infidels and their armies from the lands of Islam. The next and final step was to carry the battle into the enemy’s homeland to inaugurate the final global struggle between the true believers and the unbelievers for the mastery of the world …”

Claiming that the Western media usually misrepresents the Middle East through “honest ignorance” or “dishonest bias,” Lewis claims that very few foreign correspondents in the region have mastered the Arabic language or understand Arabic culture.

Lewis is critical of the late Edward Said, who wrote Orientalism, a book he disliked with a passion. “Said’s thesis is just plain wrong. His linking European Orientalist scholarship to European imperial expansion in the Islamic world is an absurdity.” Lewis accuses the late Palestinian American scholar of ignorance when it comes to Middle Eastern and European history, but laments that his disciples in Western universities control appointments, promotions and publications.

Lewis rejects comparisons between the Turkish massacre of Armenians in 1915 and the Nazi Holocaust. The first arose from an Armenian rebellion in collusion with Britain and Russia, he points out, while the second was purely genocidal in nature: “The attack on (German Jews) was defined wholly and solely by their racial identity…”

Not surprisingly, Lewis has definite views about his craft. As he puts it, “The responsibility, the obligation, of a historian is to tell the truth as he sees it, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. He should not allow himself to be a propagandist or to be used by propagandists.”

But he hastens to add that history is not an exact science: “It is based on evidence which is incomplete, fragmentary, inconsistent, often contradictory (and) full of gaps.”

Historical writing, he explains, should be characterized by clarity, precision and elegance.

Judging by his body of work, plus this illuminating book, Lewis has achieved these goals.