Jews in Canada live a charmed life. Living in a liberal democracy defined by such values as fairness, tolerance and inclusion, Jews have it good here, though Canada definitely has its share of bigots and racists.

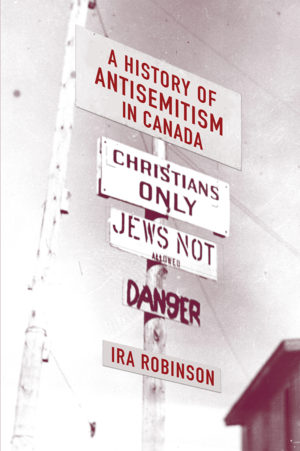

Before World War II, Canada was a far different country, a place where racism was depressingly common. Ira Robinson, a Canadian historian based in Montreal, makes that abundantly clear in A History Of Antisemitism In Canada (Wilfrid Laurier University Press), a first-class primer.

Robinson, the director of the Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies at Concordia University, examines this noxious phenomenon in pre-and post-Confederation Canada, giving readers a thorough overview of the topic.

As he correctly points out, antisemitic attitudes and notions were brought here by the French and British pioneers who settled and developed what would be Canada. How could it be otherwise? Britain, in 1290, was the first European country to expel Jews, followed by France in 1306.

Still, there was a difference between French and English Canada before the 19th century. New France, as it was called back then, forbade non-Catholic settlers, while the colonies in British North America were open to all. But even in Britain’s overseas possessions, Jews were at first denied political rights.

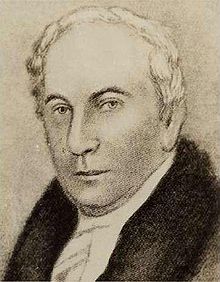

As Robinson observes, “the key moment in the history of Jewish political rights in Canada came when Ezekiel Hart, a Jewish resident of Trois-Rivieres, submitted his name as a candidate for election in the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada in 1807.” Though duly elected, he was unable to claim his seat. This outmoded convention was swept away in 1832 thanks to legislation adopted by the Legislative Assembly. By that juncture, the known Jewish population of Upper and Lower Canada was 107.

Although they were well acculturated into the Anglo-Canadian community by the mid-19th century, the few Jews in British North America faced a whole gamut of antisemitic prejudice. Still, as Robinson notes, they enjoyed legal and civil rights.

The composition of the community changed in the late 19th century and early 20th century when Yiddish-speaking Jews from the Russian empire began immigrating to Canada. But with the rising tide of ethnocentrism, Jews were classified as a “special permit” group for immigration to Canada. As a result, fewer Jews were eligible for entry into Canada.

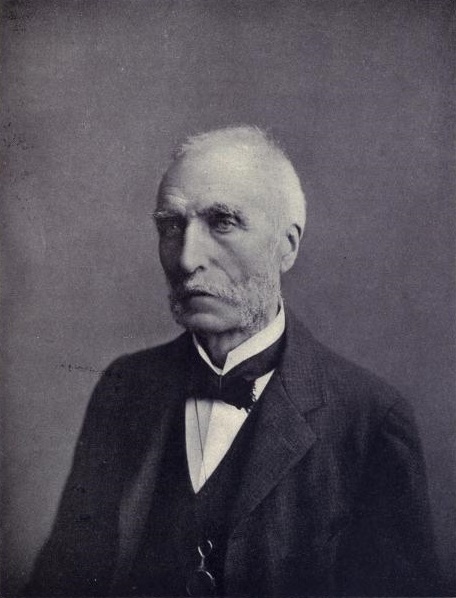

The spirit of the times was embodied by a bigot named Goldwin Smith, a British expatriate. He was, as Robinson writes, “one of the most outspoken and influential purveyors of hatred of Jews” during this increasingly problematic period. Jews, he claimed, were “the least desirable of all elements of the population.”

Robinson suggests that many French Canadians in Quebec, swayed by the powerful Catholic church, came under the baneful influence of antisemitic propagandists from France. One of them, Edouard Drumont, was the author of La France Juive, a virulent anti-Jewish tract in 19th century Europe.

Drumont’s ideas were adopted by two titans of French Canadian nationalism, the politician Henri Bourassa and the historian Lionel Groulx. According to the latter, Jews had an “innate passion for money, an often monstrous passion which lacks all scruples.” In the same vein, the notary and journalist Joseph-Edouard Plamondon branded Jews as murderers and enemies of the church and called for the revocation of their rights as citizens.

The era from World War I to World War II was a dark one for Jews. Quoting the historian Irving Abella, Robinson says Canada was “a benighted, xenophobic, antisemitic country” in which Jews were “excluded from all almost every sector of Canadian society.”

He cites examples.

In 1921, a major Toronto daily complained about a Jewish “invasion” of local public schools. In 1927, the United Church of Canada Yearbook proclaimed: “Wherever the Jew has settled, he has created new problems …” Restrictive covenants, barring the sale of property to Jews, was commonplace. Banks, insurance companies and many industries did not hire Jews.

Jewish doctors could not obtain positions in hospitals. Not until after the war was a Jewish physician able to land a clinical position at the University of Toronto. The federal government hired very few Jewish civil servants. Universities limited Jewish enrollment. Signs indicating “No Jews” or “Gentiles Only” were increasingly seen in resorts in the Laurentian mountains, north of Montreal. In 1941, Quebec City’s municipality withheld permission for the building of a new synagogue. And in 1944, when the Holocaust was a known fact, the future mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, campaigned against Jewish immigration.

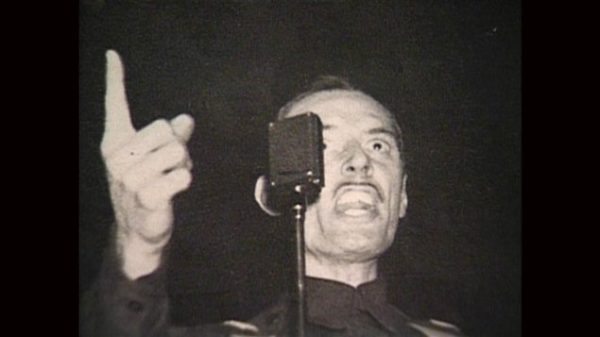

By Robinson’s reckoning, Adrien Arcand, a French Canadian politician, was probably the most notorious antisemite in the 1930s. He wrote, “Jews are like cockroaches and bugs. When you see one, you can be sure there are dozens around.” When two Jewish members of the Quebec legislature introduced a bill to ban the publication and distribution of libellous anti-Jewish material, Premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau, while condemning antisemitism, declined to support their bill.

The first Canadian human rights bills were passed before and after the war, but it was not until 1947 that a bill went as far as outlawing discrimination on the basis of race or religion. According to Robinson, the trend in the 1950s was one of “greater social acceptance of Jews.”

Nevertheless, a small but significant number of Canadians gave vent to antisemitism. Chief among them was Jim Keegstra, an Eckville, Alberta, high school teacher who dismissed the Holocaust as a hoax. By the 1990s, antisemitism in Canada had been sidelined to the margins. But one of the world’s most prominent Holocaust deniers, a German citizen named Ernst Zundel — a disciple of Arcand — lived in Toronto until he was finally deported.

Robinson, in dealing with the spectre of anti-Israel rhetoric in Canada, reminds us of its potential to morph into antisemitism. He provides two bold examples of such manifestations.

Striking a positive note toward the end of his book, he writes, “At the beginning of the twenty-first century, life has never been better for Canada’s Jews. The quotas, barriers and restrictions … are largely gone, though hardly forgotten.”

He adds, “As Abella has stated, Jews now hold prominent positions in many sectors of Canadian society that were practically unattainable a generation or two ago.” Yet, as he acknowledges, “significant pockets of discrimination and racism” still remain in Canada.