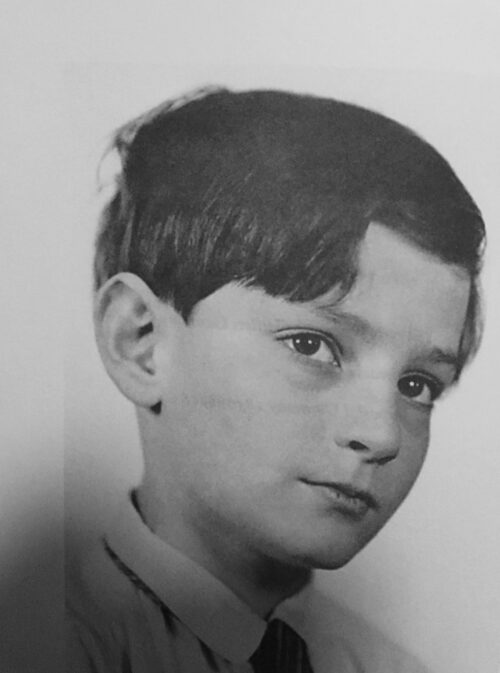

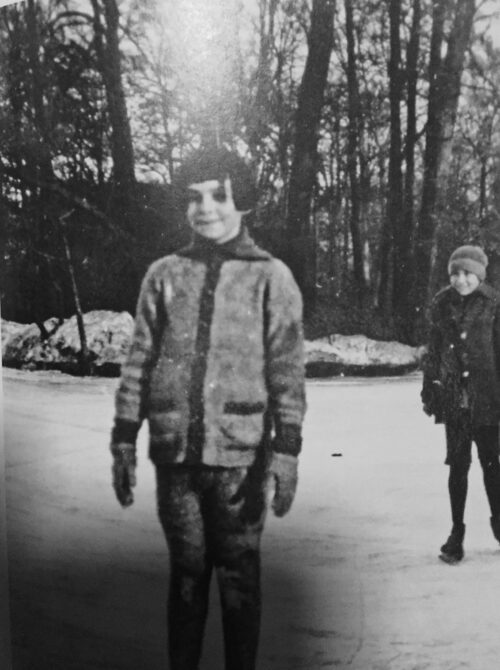

It is 1930 and Edgar Feuchtwanger, a six-year-old German Jewish boy, is standing adjacent to one of his neighbors, Adolf Hitler. The up-and-coming Austrian-born politician is waiting to be picked up outside his elegant apartment building on 16 Prinzregentenplatz in a sedate residential district of Munich.

“I can see he’s cut himself shaving, as my father sometimes does,” Feuchtwanger writes in his bracing memoir, Hitler, My Neighbor: Memories of a Jewish Childhood, 1929-1939 (Other Press). “He has blue eyes. I didn’t know that. You can’t see that in photos.”

Feuchtwanger has never seen him so close up. “He has hair in his nose, and a few in his ears. He’s shorter than I thought. He looks at me. I should look away. But I can’t. I stare at him. Maybe I should smile?”

Hitler, less than three years away from becoming Germany’s supreme leader, does not know the young boy. How could he? But Feuchtwanger knows Hitler, having watched him from his bedroom ever since he moved into the building a year ago. “Does he know I’m Jewish? I don’t want him to hate me. Or my father. Or my mother.”

Feuchtwanger ends this passage with a single sentence: “He’s climbed into a dark car, black as night, its lines as hard as stone.”

In this evocative memoir, Feuchtwanger — the scion of a prominent family and an accomplished historian — charts Hitler’s ascendancy from the vantage point of an innocent and sheltered boy who’s matured by terrible events. Intelligent, observant and discerning, he witnessed Germany’s decent into a fascist dictatorship bent on persecuting its Jewish citizens.

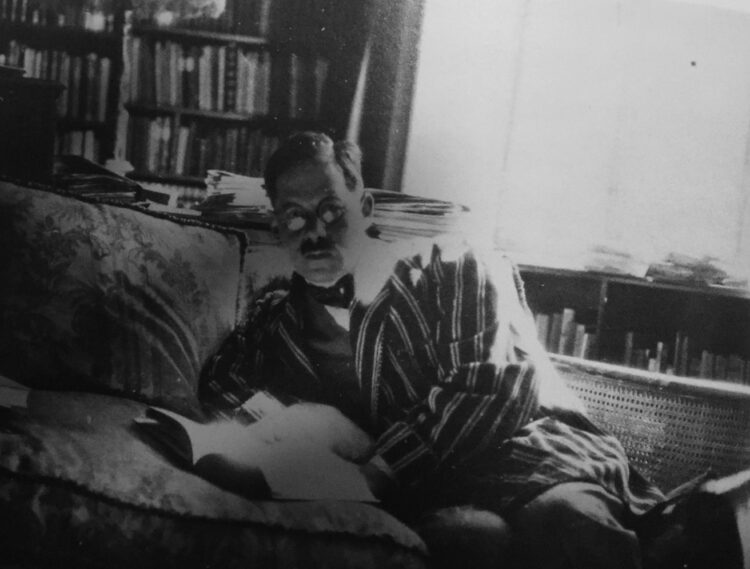

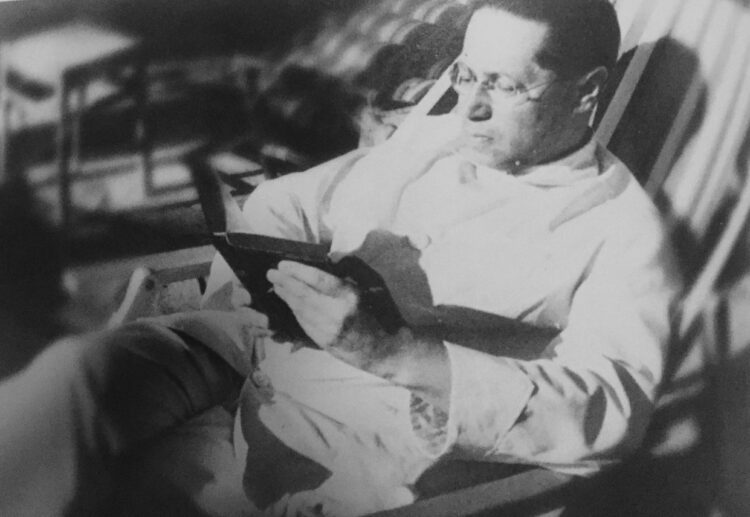

Feuchtwanger — whose father Ludwig was editor and whose uncle Lion was an author whose bestselling novel, Jew Suss, was turned into an antisemitic feature film by Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels in 1940 — enjoyed a pampered and carefree upper middle-class lifestyle until it all came crashing down with Hitler’s appointment as chancellor in 1933.

The Feuchtwangers lived in a spacious flat in one of Munich’s finest neigborhoods, and Edgar was attended to by a Christian nanny named Rosie. From this cloistered space, he witnessed the rise of Hitler and his Nazi regime.

In the two years leading up to Hitler’s political breakthrough, pro and anti-Nazi demonstrations erupted outside his apartment building. As tensions boiled over, Feuchtwanger’s mother, Erna, made him promise to stop telling people they were Jewish. His father had nothing but contempt for Hitler and his followers, but believed he had a “preposterous explanation for everything.”

Feuchtwanger’s anti-Nazi uncle, Lion, was arrested and sent to the Dachau concentration camp after Nazi thugs ransacked his home. Stripped of his German nationality, he went into exile in France before settling in California.

Shunned by a German friend who has joined the Hitler Youth organization, Feuchtwanger wonders whether he should cease being Jewish and just be a German.

As 1935 rolls around, his father visits his two sisters in Palestine. “My parents are planning to move there, so he’s on a reconnaissance trip.” More than 60,000 German Jews fleeing Nazism have already settled in Palestine.

In fact, neither his father nor mother want to live in Palestine. Jews would be better off in Europe, Ludwig says. “We’ve lived in Germany for more than 400 years. This madness will blow over like all the others that we Feuchtwangers have survived.”

He’s wrong, of course. Forbidden to work for Jews by the antisemitic Nuremberg laws, Rosie is forced to resign. It’s another ominous sign that the situation is going from bad to worse. Yet Feuchtwanger wonders whether Germany’s antisemitic laws will apply to him as well.

Eventually, his father loses his job. He works from home running a Jewish newspaper. Feuchtwanger’s half-Jewish stepsister, Dorle, has immigrated to Switzerland and lives in Lausanne with her Swiss boyfriend. Five of Ludwig’s eight siblings have now fled Germany.

Feuchtwanger no longer celebrates Christmas because Jews are not regarded as part of the German nation. “What’s the point in pretending?”

It’s 1938 and he is still keeping an eye on Hitler. “I go to school and come home. Our neighbor keeps up his peregrinations: at home one day, in Berlin the next, then in his chalet in the Alps, the Eagle’s Nest. We hear him shrieking on the radio every evening. I sometimes come across him in the morning. As our world gradually shrinks, his expands.”

Having come to terms with his pariah status, he writes, “This place is no longer our country, so why don’t we leave? I have no one to talk to at school … I’m invisible.”

His father’s friend, an Argentine diplomat, urges him and his family to leave at any price.

Kristallnacht breaks out in November 1938. “My mother is silent. Papa is ashen. The telephone never stops ringing.”

The Gestapo barges into their apartment. “I can hear them. Their voices are curt. Mama and Papa are frightened. I hear men shouting. Yelling at my parents.”

His father is arrested and taken to Dachau. The next day, his books are removed by the Gestapo. A dealer buys the valuable objects in their flat. The following week, their new identity cards arrive by mail. Every Jewish person must now add the Hebrew first name Israel to his or her name.

Ludwig returns on December 20, his eyes sunken and his gray faced patched with purplish-blue bruises. “Mama appeared. She gave a little cry and clung to the two of us.”

Shortly afterward, Ludwig informs his son they’re leaving Germany, having been granted a family visa by Britain. “Since we received confirmation that we’re leaving for London, I can’t help smiling when I see the Fuhrer’s window lit up at night. He doesn’t know I’m watching him. He has no inkling that here, just opposite his apartment, a child has grown up over the last 10 years, a child who will one day bear witness.”

On February 14, 1939, Feuchtwanger leaves Germany. His parents will join him in a few weeks. “We have nothing to fear today. In a few days we won’t be German anymore. Ever more.”

In Britain, Feuchtwanger studied at Cambridge University, taught history at Southampton University, and wrote a succession of books about his birthplace, including From Weimar to Hitler: Germany, 1918-1933.

He can now proudly add Hitler, My Neighbor to his bibliography.