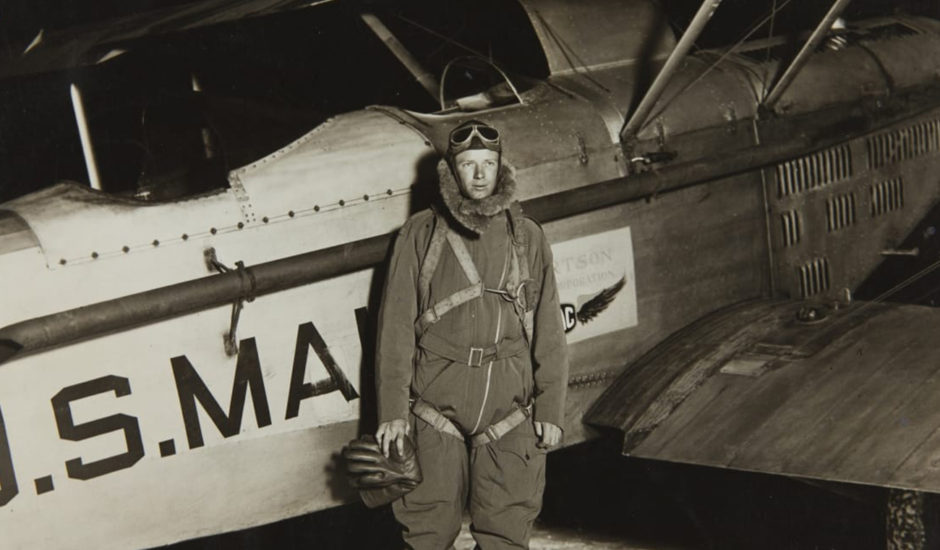

Three months before Japan attacked the U.S. fleet in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Charles Lindbergh addressed a crowd in Des Moines, Iowa, to rail against the prospect of American intervention in World War II. Speaking as a member of the American First Committee, a non-profit isolationist organization that was officially incorporated in September of 1940, he claimed that three groups were ominously conspiring to push the United States into that conflict: “the British, the Jewish, and the Roosevelt administration.”

Lindbergh, an American hero who was the first person to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean, focused his comments on Jews. In light of the Nazi regime’s persecution of German Jews, he said, he understood why American Jews sought a war against Germany. But hastening to add that Jewish Americans would be one of the first to feel the consequences, he went on to say that Jews posed a unique danger to the United States because of their “large ownership and influence in our motion pictures, our press, our radio and our government.” In closing, Lindbergh expressed the hope that American Jews would stop trying to embroil the United States in the war.

A few weeks before he spoke in Des Moines, Lindbergh, in his journal, wrote, “We feel that Jews are among the most active of the war agitators, and among the most influential. We feel that, on the one hand, it is essential to avoid anything approving a pogrom; and that, on the other hand, it is just as essential to combat the pressure the Jews are bringing on this country to enter the war. This Jewish influence is subtle, dangerous and very difficult to expose.” As “a race,” he noted, “they seem to invariably cause trouble.” The only solution was “frank and open discussion” of “the Jewish problem.”

Lindbergh’s speech, which encapsulated much of his ill feelings toward Jews, set off a firestorm of criticism. Jewish organizations denounced his slurs and demanded a retraction. Wendell Willkie, Roosevelt’s Republican rival, decried his bigotry. Thomas Dewey, who would be Roosevelt’ opponent in the 1944 presidential election, said Lindbergh had inexcusably abused his right of freedom of speech.

Faced with such universal condemnation, the American First Committee denied it was antisemitic and blamed interventionists for inserting “the race issue” into the debate. Taking their cue from President Franklin Roosevelt, who said that the United States could not afford to stay out of the war, interventionists believed that America was duty-bound to abandon its policy of neutrality, enter the war and, at the very least, provide material assistance to besieged allies like Britain.

As Bradley W. Hart writes in his highly readable book, Hitler’s American Friends: The Third Reich’s Supporters in the United States (Thomas Dunne Books), the American First Committee may not have been an antisemitic body. But its overriding objective was perfectly in accord with Germany’s intentions, and some of its supporters, apart from respectable politicians and business leaders, were right-wing extremists and antisemites.

By far the biggest and most vocal organization of its kind in the United States, with more than 800,000 members concentrated mainly in the Midwest, the American First Committee was led by Robert E. Wood, the chairman of Sears, Roebuck and Company, the country’s largest department store chain.

As Hart suggests, the Nazi propaganda apparatus in the United States used the American First Committee to further its aims: “America First was the culmination of years of Nazi disinformation and propaganda, coupled with the extremism of home-grown fascism.” For all intents and purposes, the American First movement was one of Germany’s “key American friends.” As for Lindbergh, he became the de facto leader of the broad right-wing coalition that vehemently opposed the entry of the United States into the war.

According to Hart, a professor of history at California State University, the glue that held Nazi Germany’s American supporters/sympathizers together was antisemitism. As he puts it, “Antisemitism was effectively the entry point to becoming one of (Adolf) Hitler’s American friends for the vast majority who travelled that path.”

Aside from the American First Committee, the most prominent pro-isolationist and pro-German bodies in the United States were the German American Bund and the Silver Legion. On an individual level, the chief pro-Nazi propagandists were Gerald Burton Winrod, a Kansas Protestant minister, and Father Charles Coughlin, a Canadian-born Catholic priest based in Detroit.

The German government itself ran an extensive spy network out of its consulate in San Francisco. Its consul general, Fritz Wiedemann, had been Hitler’s commanding officer during World War I. Many of its spies were American citizens whose motivations ranged from money to sex. Hart says that the German espionage and intelligence ring, which sought U.S. military technology, was smashed by the FBI by late 1941, the year Germany’s consulates in the United States were closed.

The German American Bund, originally known as the Friends of the New Germany, was formed in 1936 and headquartered in the Yorkville district of New York City. It had a membership of 10,000 to 30,000 and many more sympathizers. Its first leader, Fritz Julius Kuhn, was born in Munich in 1896 and fought in World War I as a machine gunner. He joined the Nazi Party in 1921, shortly after its formation, and settled in the United States five years later.

The Bund received some financial support from the Nazi Party in Germany, but in 1938, the German ambassador to the United States recommended that Kuhn be cut off. The foreign ministry in Berlin had already reached the conclusion that Germany’s association with Kuhn, who had been deemed a national security threat to the United States, would endanger its bilateral relations with Washington. Subsequently, Germany forbade its citizens from joining the Bund.

Kuhn, having been exposed as an embezzler, was evicted from the Bund and succeeded by Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze. By then, the Bund was on a downward spiral. Kunze abruptly resigned in 1941, and his successor, George Froboese, committed suicide in 1942.

In Hart’s opinion, the Bund, never having made much headway, was “a miserable failure.”

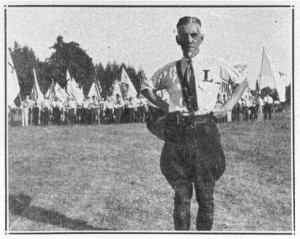

The Silver Shirts, founded by the former Hollywood screenwriter, failed novelist and mystic William Dudley Pelley, had a membership approaching that of the German American Bund. Explicitly antisemitic, he and his associates were open about their desire to establish a fascist regime, or a Christian Commonwealth, in the United States.

In his mind, Jews controlled the media, politicians and financial systems and sowed unrest through communism. Under his plan, Jews would be concentrated in a single city in each state and would be closely monitored to foil their machinations.

Pelley constantly ran afoul of the law, but in 1942 he was indicted for sedition under the Espionage Act. He spent the remainder of the war mired in protracted legal battles that drained his finances.

Hart thinks that Pelley could have become a leader of the far right had he exercised a greater degree of personal discipline. “Pelley could have been formidable. As it turned out, he was merely a flash in the pan …”

Like Pelley, Coughlin equated Judaism with communism and claimed that Jewish bankers had financed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution. Through his popular radio show and newspaper, Social Justice, he was a master of the mass media. His biggest supporters were East Coast Irish and German immigrants who had been mauled by the Depression.

After Coughlin declared the war had been caused by the “race of Jews” rather than by German aggression, the postmaster general suspended the distribution of Social Justice on the grounds that it might harm military morale.

Coughlin’s career went into a steep decline and he returned to his duties as a parish priest.

Winrod, an antisemitic rabble-rouser in the mould of Nazi fanatic Julius Streicher, was a devotee of the Czarist forgery the Protocols of the Elders of Zion and an admirer of Hitler. He ran for a U.S. Senate seat in Kansas and received 53,000 votes in the primary.

Hart says that more than two dozen U.S. senators and congressmen were receptive to the anti-British invective disseminated by the German propaganda machine, which was directed by George Sylvester Viereck. He was an ethnic German American who, in Hart’s opinion, was “the Nazis’ most effective tool for recruiting new American friends” on Capitol Hill.

Nazi influence also seeped into university campuses by means of German exchange students, who were given mostly “unchallenged platforms” from which to spout their views.

“American universities essentially allowed antisemitic and pro-Nazi views to go virtually unchallenged. A more courageous stand would have gone far to discredit Nazism and prejudice among the next generation of Americans. Instead, the country’s intellectual leaders chose a path of engagement, legitimization, and tacit support that would carry long-term consequences.”

Looking back at the period from the 1930s to the 1940s, Hart is unequivocal: “Had Hitler’s American friends been successful, the U.S. would never have entered World War II, Britain would have fallen under Nazi occupation and, ultimately, a version of National Socialism would have taken root in the United States.”

Thankfully, the interventionists prevailed over the isolationists, thereby defeating Nazi Germany and preserving American democracy.