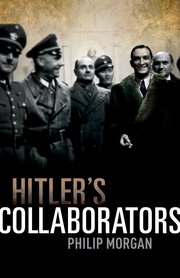

It comes as no surprise that home-grown fascists in Western Europe collaborated with the German occupation of their respective countries during World War II. Philip Morgan, in Hitler’s Collaborators: Choosing Between Bad and Worse in Nazi-Occupied Europe (Oxford University Press), mentions them in his wide-ranging book, of course. But what really interests him are not the usual suspects, but the procession of civil servants and businessmen who engaged in this type of treasonous behavior.

As he points out, collaboration was a fairly common phenomenon, especially in countries like France, Holland, Denmark, Belgium and Norway, where the local civil service and police force were left in place by the Germans to manage internal affairs. Citing the figures of a researcher, Morgan — a senior fellow at the University of Hull in Britain — says that 94 per 100,000 of the population were imprisoned for collaboration in France, 374 in Denmark, 419 in Holland, 596 in Belgium and 633 in Norway.

“From the summer of 1940, officials and businessmen in the occupied territories collaborated with each other, and with the Germans, in order to restart economic activity and end the scourge of mass unemployment in countries that had barely recovered from the effects of the Great Depression by the time of the outbreak of the war,” he writes. “Economic recovery and the absorption of unemployment were the mutual concern of governments, government officials, and German occupation authorities. They shared the same broad perspective that, by removing a likely source of popular discontent, they could help reestablish law and order, restore social calm and stability, and secure a ‘peaceful’ occupation.”

These initiatives were helpful, but in terms of job creation, German spending on the repair of roads, bridges and railways and the building of barracks, airfields and shipyards also had an impact. “The German occupations in their own right ignited a construction boom across the occupied territories that lasted well into the war,” he says.

But as he points out, the inevitable growth of resistance to occupation enabled the dreaded SS to influence and take over policing in the occupied territories.

Conditions in each country varied.

According to Morgan, Denmark was the only country that retained its monarchy, parliamentary government and national institutions.

Norway was the only country where the local Nazi party, headed by Vidkun Quisling, was in power from the start of the occupation.

France, governed by Henri Philippe Petain, was the only country that secured an armistice that, in due course, would be superseded by a peace treaty between the Germans and the French. Holland was ruled by the reichkommissar and Austrian Nazi leader Arthur Seyys-Inquart rather than by a German military administrator.

Morgan claims that the greatest challenge to collaboration was the enactment of antisemitic measures in the early years of the occupation. Keen to establish working relationships with local officials, non-ideological German authorities feared that the imposition of anti-Jewish edicts would likely be unpopular and strain both the principle and practice of collaboration.

In Denmark, for example, the chief German occupation official did not insist on antisemitic measures so as to protect the otherwise productive relationship with the Danish government. But in France, Vichy officials enacted antisemitic laws because they were regarded as steps toward the transformation of French society. In other words, French officials and police in the occupied zone carried out German decrees against Jews as an exercise in and assertion of sovereignty.

The Germans were only too pleased to transfer that task to Vichy officials like Louis Darquier de Pellepoix and Jean Leguay, while protecting the rationale behind collaboration — the minimal deployment of German personnel and the maximum deployment of French officials.

In Holland, where three-quarters of Dutch Jews perished during the course of the Holocaust, about 2,000 “non-Aryan” civil servants out of some 200,000 were dismissed from their positions. Among them was the Jewish president of the Supreme Court, Lodewijk Visser. His fellow judges remained silent over his mistreatment, fearing that their opposition would have adverse effects on the judicial system.

Yet interestingly enough, the Jewish secretary general for economic affairs in Holland, Max Hirschfeld, whose family had converted to Christianity, was not touched by antisemitic laws. Seyss-Inquart effectively turned a blind eye to his Jewish origins because he was such an effective official.

Dutch police played a role in the roundup of Jews, but by 1943 their commitment to this task had begun to waver with the realization that their policing of the occupation was unpopular.

In closing, Morgan says that high-level collaborators used various rationales to justify their behavior.

Petain let it be known that he had saved France from being treated like Poland. Danish, Dutch, Belgium and Norwegian officials said they had collaborated to retain the respective independence of their nations.

“Most of them saw collaboration as a way of avoiding, or mitigating, not a hypothetical but an actual or imminent national catastrophe,” writes Morgan.

In the final analysis, however, collaborators were the enablers of the Nazi occupation.