The summer Olympic Games of 1936 in Berlin set a precedent for future Olympics.

In terms of packaging and presentation, they would be a vehicle for slick propaganda — a projection of German national pride and glory. Daniel Kontur’s 44-minute documentary, Hitler’s Olympics, which is now available on the Netflix streaming service, deftly explores this theme.

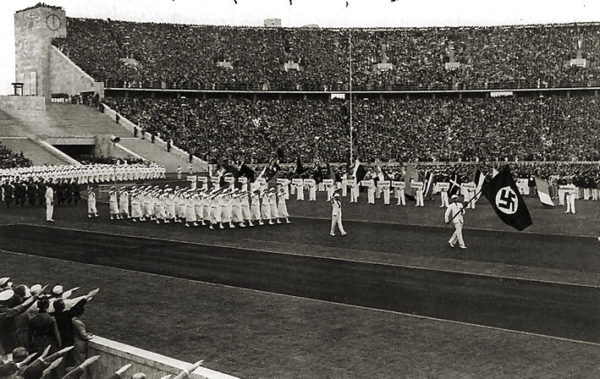

Described as a “huge and deafening event” of theater, pageantry and excitement, they were the first games in modern times to mix sports and politics. Never before had a host nation foisted its national ideology on the Olympics so blatantly. Germany used the games to showcase the virtues of National Socialism.

On the playing field, the Nazis introduced innovations that succeeding host countries would readily adopt — the grand opening ceremony, the stirring march-in of competing teams and the heart-pounding arrival of the Olympic torch.

Viewed in perspective, the Nazi Olympics would be the template of the modern Olympic Games.

The International Olympic Committee awarded them to Berlin in 1931, about two years before Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of Germany. The spirit of bringing people together in Germany, defeated in World War I and banned from participating in the 1924 games in Paris, was the catalyst for granting the Olympics to Berlin. In 1912, the German capital had been designated as the host nation of the 1914 games, but they were summarily cancelled due to the outbreak of the great war.

Initially, Hitler was less than enthusiastic about the games, which, in effect, he inherited. Joseph Goebbels, the minister of propaganda, convinced him of its immense potential to highlight Germany’s new and exalted place in the international community.

There was a problem, of course. How could Hitler’s antisemitic regime be reconciled with the Olympic spirit of amity and friendship?

In 1934, the president of the American Olympic Committee, Avery Brundage, was invited to Germany to ascertain whether the Nazis would allow Jewish athletes on the German team or into Germany itself. Bamboozled by Hitler’s glib public relations juggernaut, Brundage returned to the United States with the conviction that Jewish athletes would face no discrimination in Germany.

For the duration of the two-week games, there was a deliberate pause in the persecution of German Jews as antisemitic signs throughout Germany temporarily disappeared from sight. And a handful of Jewish athletes, like the fencer Helene Mayer, were permitted to join the German squad.

Oddly enough, she became a poster girl for Nazism, sticking out her hand in a stiff arm Nazi salute after receiving a silver medal. Jews in Germany, in particular, were disgusted by her toadying gesture. But perhaps she was terrified due to the fact that her family still lived in Germany, the film speculates.

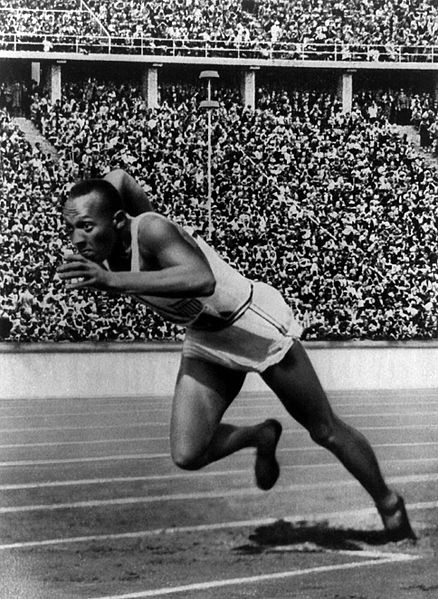

As it suggests, Jesse Owens, the African America sprinter and long jumper, was the star of the games. Having won four gold medals, he single-handedly shattered the myth of Aryan superiority. Germany, nonetheless, led the medal count when the games ended.

Hitler and Goebbels got what they wished for — glowing stories from the compliant press corps covering the games. Blinded by the majisterial power of the games, they seemed oblivious to the deeply autocratic and anti-Jewish nature of the regime.

A sad postscript is that Owens did not receive the lucrative sponsorship deals an athlete of his calibre could have expected after winning four gold medals. A victim of Jim Crow customs and laws still very much prevalent in the United States, he was forced to take menial jobs to survive.

America of the 1930s was a society of rampant and ingrained racism — a mirror image, perhaps, of Nazi Germany.