Adolf Hitler captured hearts and minds because the bulk of Germans shared his beliefs and grievances. They embraced Nazi ideology, an amalgam of nationalism, socialism, militarism and antisemitic conspiracy theories, and rejected the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, which blamed Germany for the outbreak of World War I, reduced its territory, limited its armed forces, and forced it to pay crippling reparations.

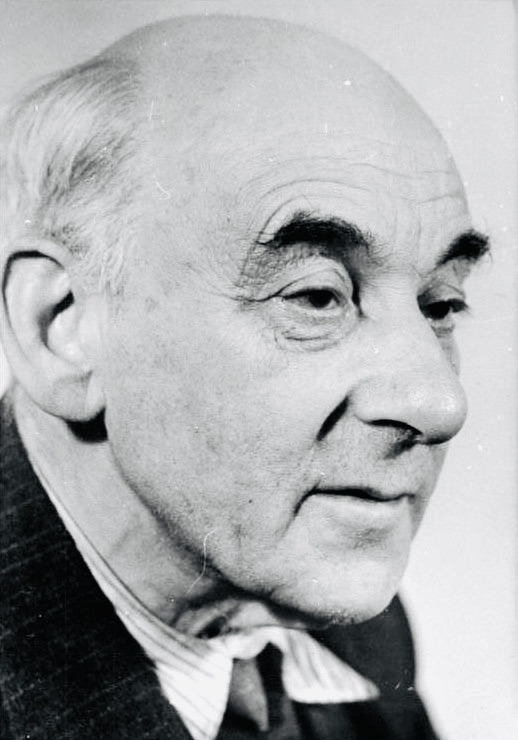

As the American historian Robert Gellately observes in the paperback edition of Hitler’s True Believers: How Ordinary Germans Became Nazis (Oxford University Press), a lucid and penetrating book, Hitler’s ideas were anything but unique or original to his followers, particularly his most fervent ones, the “true believers.”

“This cluster of ideas proved to be successful precisely because they were original and were already embedded in Germany’s political culture,” writes Gellately, a Florida State University professor of history and an authority on Nazi Germany.

National Socialism explained all that was wrong in Germany, including its class-torn society, and offered a solution on how to put it right in a Volksgemeinschaft, a racially homogeneous and harmonious “community of the people” bereft of Jews.

The Nazi movement would rejuvenate Germany and restore hope, though Hitler acknowledged that generations would elapse before it could create the kind of order he desired. But between 1933 and 1945, an era that encompassed the Third Reich, Hitler and his associates managed with remarkable suddenness to influence social, cultural and political life from top to bottom.

The first Germans to join the Nazi Party were fired up by a sense of outraged nationalism, even victimhood, sparked by the unsuccessful war and the Versailles Treaty that Germany was forced to sign. Hitler’s earliest acolytes were driven by strong socialist and antisemitic attitudes, which were already baked into the political culture despite the full emancipation of Jews about half a century before.

“Wrapped together, nationalism, socialism and antisemitism, along with the quest for ‘living space,’ constituted the essential core of Hitler’s doctrine,” he writes.

But as he adds, Nazism would not have succeeded without two economic disasters — the horrendous inflation of 1923, which wiped out the savings of millions of Germans, and the Great Depression, which started in 1929.

During these years, the Nazi Party’s membership peaked at around 55,000, compared to the 1.2 million and the 294,000 Germans who respectively belonged to the Socialist Party and the Communist Party. But by the late 1930s, with Hitler fully in control of the country, two-thirds of Germans were members of the Nazi Party and its affiliate organizations running the gamut from the German Labor Front to the Hitler Youth.

What remains stunning is that tens of millions of people in a culturally and technologically nation as advanced as Germany accommodated themselves to “the tenets of an extremist doctrine laced with hatred and laden with obvious murderous implications.”

As Gellately points out, the Nazi regime was “not remotely threatened by collapse or betrayal from within,” the 1944 assassination plot against Hitler notwithstanding. “It had to be brought down from outside” by Allied armies.

He believes that antisemitism was at the core of Hitler’s beliefs from 1919 onward. “We don’t want to be emotional antisemites, who want to create a mood for pogroms,” Hitler said. “What animates us is the unrelenting determination to attack the evil at its source, and to eradicate it root and branch.” From that point onward, Hitler described Jews as “a bacillus” who had to be removed and exterminated.

Students at universities were especially receptive to Hitler’s genocidal thinking. “National Socialism found fertile ground at … institutions of higher learning,” he says. “University students, with their tradition of antisemitism, needed no prompting to harass both Jewish students and professors.”

By Gellately’s estimate, 30 percent of the SS officer corps had university degrees, with law graduates comprising the single largest professional group. He notes that SS officers, having been steeped in an illiberal academic culture, had supported the disruption of classes of leftist and Jewish professors.

The Nazis drew on the support of racist nationalists who had been active in one of Germany’s 125 volkisch (racialist) organizations and who sought to translate their notions into reality. Gellately cites several of these groups — the German Racial Protection and Defence League, the German Nationalist People’s Party, and the Pan-German League. Still others had belonged to the paramilitary Freikorps, which emerged after World War I.

Among the early true believers who joined the Nazis were Alfred Rosenberg, Heinrich Himmler and Julius Streicher.

Rosenberg, an ethnic German born in Estonia, wrote an introduction to, and analysis of, the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, an antisemitic screed concocted by the Russian police. And after 1941, he was in charge of the territories conquered in the Soviet Union. Himmler, the SS chieftain, was one of the architects of the Holocaust. Streicher edited the Jew-baiting rag, Der Sturmer.

What they all had in common was a profound antipathy toward Jews and the liberal Weimar Republic and a passionate belief in the restoration of lost German territory and the rebuilding of the armed forces.

Economic desperation and the fear of communism attracted farmers, craftsmen, shopkeepers and physicians to the Nazi cause, with its propagandists reiterating that “Marxism is Judaism” and “Judaism is Marxism.”

The Nazi Party received support from all social classes, including the elite, and 40 percent of its votes emanated from working-class households. In the March 5, 1933 general election, the Nazis won 43.9 percent of the vote, the largest percentage of any party during the previous Weimar Republic. On a per capita basis, more Protestants than Catholics voted for Hitler, while voters in rural areas tended to favor Nazi candidates.

Antisemitism remained at the core of the Nazi regime from the moment Hitler was appointed chancellor on January 30, 1933. Jews, comprising less than one percent of the population, were subjected to assaults, shaming rituals, boycotts and restrictions.

They were also stripped of civil servant jobs, deprived of citizenship under the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, officially cast out of the Volksgemeinschaft, and exposed to a massive nation-wide pogrom during Kristallnacht in 1938. During this outburst of unrestrained violence, 360 synagogues were destroyed and 31 Jewish-owned department stores were burned down or demolished.

The majority of Germans watched passively as this disgraceful spectacle unfolded, but some participated in it. Victor Klemperer, a Jewish academic and a convert to Christianity whose non-Jewish wife protected him from harm, was profoundly disillusioned by the turn of events: “How deeply Hitler’s attitudes are rooted in the German people, how good the preparations were for his Aryan doctrine, how unbelievably I have deceived myself my whole life long, when I imagined myself to belong to Germany, and how completely homeless I am.”

Hitler’s quest to exterminate Jews was on full display in a speech to the Reichstag on January 30, 1939, the sixth anniversary of his appointment as chancellor. Claiming that Jews were conspiring to incite a war, he delivered a chilling prophecy: “This time the result would not be the Bolshevization of the world but the extermination of the Jewish race in Europe.”

“Never had a leader of a modern world power announced such a murderous threat against an entire class of noncombatants,” says Gellately.

In the pages to follow, he sets out Hitler’s plan of conquest and campaign of ethnic cleansing after Germany’s invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939. Intent on erasing Poland from the map, the Nazis divided it into three zones, including one section that would be incorporated into Germany.

On the eve of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, Hitler told Alfred Jodl, the Wehrmacht’s chief of operations, that the impending campaign would be more than a clash of arms and “a struggle between two ideologies.” It would be “a war of extermination,” he declared.

And so it was.

The Wehrmacht participated in some of the atrocities, with Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau justifying the mass murder of Jews on the grounds that they were “sub-humans.”

Another Nazi true believer, Odilo Globocnik, was placed in charge of constructing several extermination camps, notably Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, where more than 1.5 million Jews perished.

Hitler, in his final anniversary speech on January 30, 1945, hewed to the theme that Jews were conspiring to exterminate “our people.”

The legacy he left behind after committing suicide in his Berlin bunker was exceedingly grim. As Gellately puts it, “The Third Reich translated the most murderous aspects of National Socialist ideology into practice, as Hitler and those under his command instituted unimaginable crimes, including the Holocaust. They brought death and destruction everywhere they went, and they left (Germany) reduced, divided and humiliated.”