Holland, a nation celebrated for tolerance and compassion, had a mercurial relationship with the Holocaust.

Dutch Jews who emerged from hiding and from German concentration camps in the wake of Holland’s liberation from Nazi tyranny in 1945 learned to their utter dismay and disgust that they would be fined for not having paid their property tax during Germany’s five-year occupation of the country.

To add salt to the wound, they also discovered they would have to pay gas and electricity bills accrued by the non-Jewish occupants of their expropriated homes.

It staggers the imagination that Dutch authorities could have been so obtuse, insensitive and cruel. Could they not understand that Dutch Jews were unable to settle their bills during this dark and desperate period?

This was truly a Kafkaesque situation.

Having been informed they were in arrears on their tax bills, Jewish property owners in postwar Holland lodged appeals, but to no avail. The bills had to be paid, whatever the circumstances may have been.

Last week, the municipality of The Hague, the Dutch capital, finally came to its senses, belatedly announcing it had agreed to offer $2.7 million to Holocaust survivors or their descendants in restitution payments for its “immoral” imposition of taxes. This development occurred about a year after Amsterdam’s city council allocated $11 million to non-governmental organizations as compensation for similar practices.

These payments may help heal old wounds, but Holland still has a considerable way to go before the account is fully settled.

Holland, having been invaded by Germany in the spring of 1940, showed the world two different faces.

On the one hand, a strong anti-Nazi resistance movement, which helped Jews, earned universal admiration. Anne Frank — the Jewish diarist — and her family benefited from the courage of ordinary Dutch people who could not abide Nazi racism and oppression. As a result, more than 5,200 Dutch gentiles have been honoured as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial cum-education and research centre in Jerusalem. Only Poland has more recipients.

On the other hand, Holland lives with a dubious distinction. Seventy five percent of its prewar Jewish population of 140,000 perished during the war, the highest death rate in Nazi-occupied Western Europe. In France, for example, the rate was 25 percent.

There are a multiplicity of reasons for Holland’s status as a Jewish charnel house, but one factor must surely be that a considerable proportion of Dutch people chose to collaborate with the German occupiers, even though Holland had been a safe haven for Jews since the 16th century.

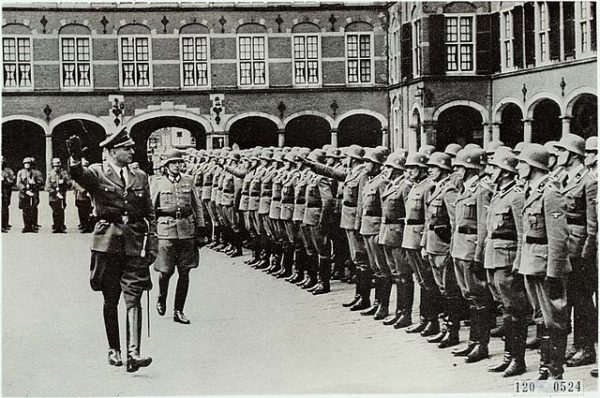

The Dutch civil service cooperated with the German administration, headed by Arthur Seyys-Inquart. Twenty two thousand Dutchmen volunteered for the Waffen-SS, the highest proportion in Nazi-occupied Europe. The Germans could count on the support of the Dutch Nazi Party, which had a membership of some 100,000. Dutch police assisted the Germans in rounding up Jews slated for deportation to Nazi extermination camps in Poland, and the national railway company transported Jews to these destinations.

Admittedly, Holland has tried to make amends for its shortcomings. The government has funnelled restitution payments to the Jewish community, and Holland’s railway company has issued an apology for its role in the deportation of 107,000 Jews to Nazi concentration camps such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibor. They were sent to Poland via Westerbork, a Dutch transit camp which had originally housed some 25,000 German Jewish refugees.

In 2005, the Dutch prime minister strongly condemned Holland’s complicity in the Holocaust, lamenting its callous treatment of Jews returning from Nazi camps. And while the leaders of France, Belgium and Luxembourg have officially apologized for the ordeal their Jewish citizens endured, the current Dutch prime minister, Mark Rutte, has resisted calls to issue a formal apology.

Rutte should do the right thing and apologize, thereby closing an ambivalent chapter in Dutch history.