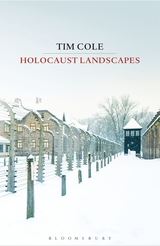

The Holocaust was not a single, monolithic event but rather a series of events that unfolded in different places at different times, a theme British scholar Tim Cole deftly pursues in Holocaust Landscapes, published by Bloomsbury.

Cole, a social historian at Bristol University who’s written several books about the Holocaust, explores it from various vantage points: expulsion, ghettoization, shootings and industrial-style killings in extermination camps. Cole also casts a discerning eye on the trains that carried Jews to their deaths and, conversely, on Jews who evaded the Nazis and went into hiding.

Whenever possible, he relies on the first-hand accounts of Holocaust survivors to enrich his narrative.

Appropriately enough, he begins on Kristallnacht, the nation-wide pogrom in Germany in 1938 that presaged the Holocaust. Focusing on the city of Breslau and a German-Jewish student named Gerda Bachman, Cole uses her grim story to illuminate the tragedy that befell German Jews.

He goes on to discuss the territorial solutions the Nazi regime considered to resolve the so-called Jewish question — the Nisko plan to create a reservation east of Lublin and the scheme to resettle Jews on the island of Madagascar. Neither of these plans materialized, prompting the Nazis to herd Jews into ghettos.

In Warsaw, which had a pre-war Jewish population of around 360,000, the ghetto housed as many as 460,000 Jews. “In these concentrated and segregated places, a combination of overcrowding and an inadequate diet proved devastating,” he writes. “The presence of the dying and the dead on the streets of the ghetto are recurring images in survivors’ memoirs, oral history accounts and ghetto diaries.”

The existence of a smuggling economy in the Warsaw ghetto, he adds, created a new class of nouveau riche Jews. The ghetto was not a single, homogeneous space but rather a “variegated patchwork” of streets of poor and some rich Jews.

As for mass shootings, 1.5 million Jews in the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union were murdered by the Einsatzgruppen in three waves in 1941, 1942 and 1943. Jews who managed to escape tended to hide in forests, which were regarded as unknown and feared spaces. Their survival rate was pitiful. Less than 10 percent of the tens of thousands who headed into the woods survived. Winter was the safest season to live in a forest, when thick snow insulated and camouflaged bunkers. But these benefits were outweighed by harsh conditions and the difficulty in finding food.

As he points out, the technology for mass killing was developed in four camps — Chelmno, Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, where Polish Jews were murdered en masse in 1942 and 1943. Once they were razed to the ground, Auschwitz-Birkenau was the only death camp with the facilities to kill Jews on a massive scale.

By his estimate, 1942 was the bloodiest year of the Holocaust, when 2.7 million Jews were murdered.

From 1941 until 1944, an estimated three million Jews were deported to concentration camps in about 2,000 trains, he says. It took only 147 trains to deport some 430,000 Hungarian Jews.

Survivors report that Jews were packed into box cars like herrings or sardines in cans. “There was no room to move,” Cole quotes one survivor as saying. “We were practically on top of one another…” Another survivor recalls that “the train ride was utterly horrendous. People died. There was no water. There were no sanitary facilities. There was no food.”

Jews who managed to avoid such a fate could flee to the Soviet Union, Sweden or Switzerland. Jews unable to exercise that option could assume a new identity and live on false papers as Christians, lie low and go into hiding, or leave Europe altogether.

Cole devotes an entire chapter to Hungary, which was “an island of safety” until Germany’s occupation in 1944. Hungary had marginalized and persecuted its 600,000 Jewish citizens, but in the wake of the German invasion, persecution turned to murder. Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish businessman, saved tens of thousands of Jews in Budapest, but the Arrow Cross, a home-grown fascist militia aligned with Germany, succeeded in killing thousands of Jews before the Red Army conquered Hungary.

Toward the end of his book, Cole provides a graphic description of the horrendous “death marches” that took place after the evacuation of Auschwitz in January of 1945. He also describes the horrible conditions that prevailed in the Bergen-Belsen camp at the close of the war.

These are among the terrifying places he examines in Holocaust Landscapes.