A fairly significant event took place in Cairo on January 24, when close to 50 people attended a ceremony commemorating International Holocaust Remembrance Day, which is being observed today to commemorate the Red Army’s liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland.

The gathering, the first of its kind in Egypt, was held at a five-star hotel on the banks of the Nile River and attracted foreign diplomats, human rights activists, former members of Egypt’s parliament, the leader of Egypt’s depleted Jewish community, and businessmen.

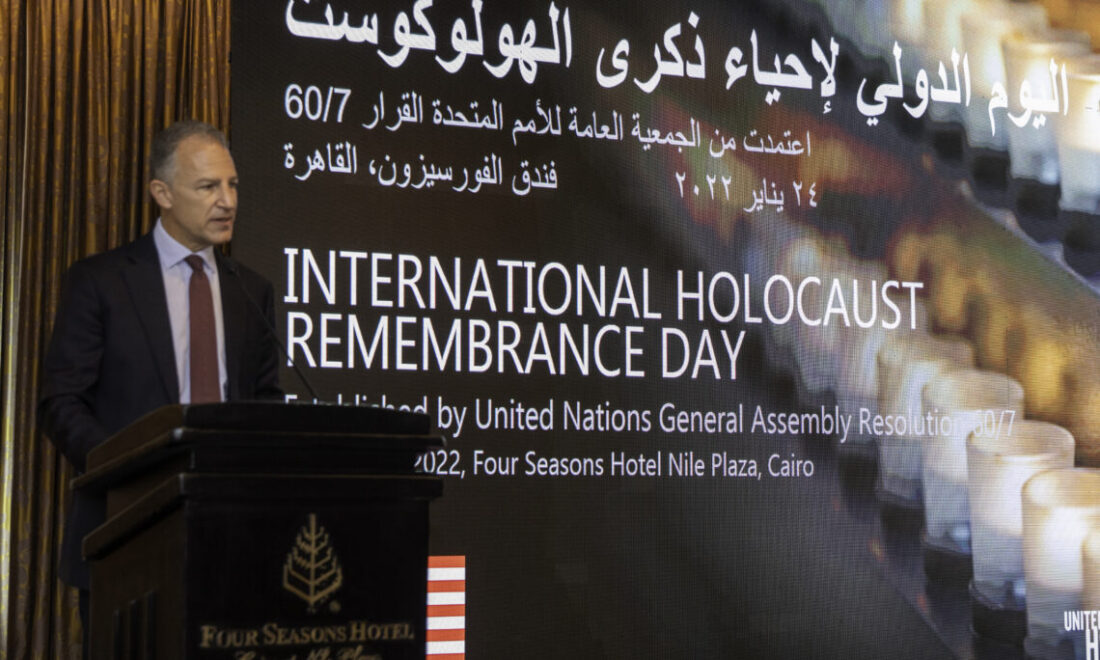

It was hosted by the U.S. embassy and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

The U.S. ambassador to Egypt, Jonathan Cohen, delivered a speech in which he praised Mohamed Helmy, an Egyptian doctor who lived in Berlin during the Third Reich. “Dr. Helmy secretly sheltered a Jewish teenager who was hunted by the Gestapo, saving her at a time of maximum danger, and putting himself at great risk,” said Cohen. “Thanks to Dr. Helmy’s bravery, the young woman survived and immigrated to the United States after the war.”

To Robert Satloff, the executive director of the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, this week’s event in Cairo was “symbolically very important” because it took place in the largest, most populous and most influential Arab state, he told Jewish Insider, an online publication.

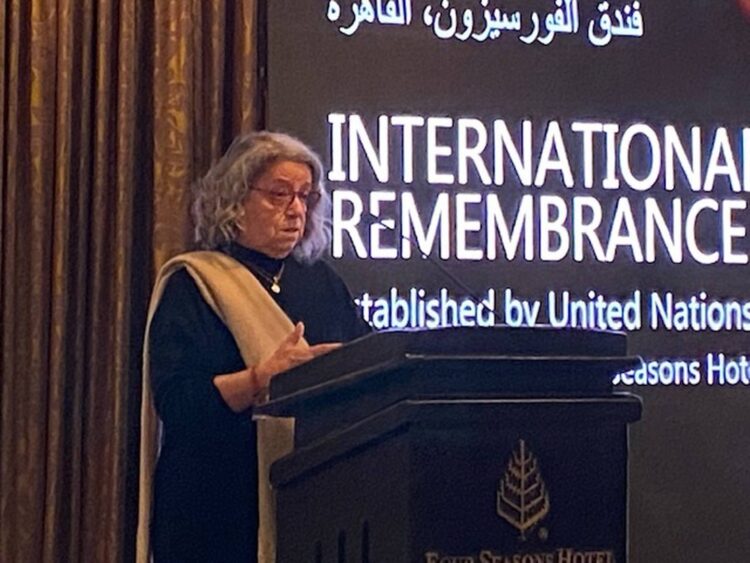

Mina Abdelmalak, the museum’s Arabic outreach director, was just as upbeat. “If you had told me a few years ago that such an event would take place in Cairo, I would have laughed,” he said, implicitly alluding to the prevalence of anti-Israel sentiment and Holocaust denial in Egypt.

Although Egypt was the first Arab state to sign a peace treaty with Israel, it has been a cold government-to-government peace rather than a people-to-people grassroots peace.

There are no cultural relations between Egypt and Israel. The Egyptian government discourages tourism to Israel. The media is anti-Israel and occasionally antisemitic. The intellectual elite boycotts Israel and is active in anti-normalization organizations.

In short, the vast majority of Egyptians still regard Israel as an illegitimate pariah nation, an enemy of the Arab world. And in their eyes, the Holocaust is historically suspect, solely designed to enhance Israel’s legitimacy.

Egypt’s president, Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, has warmed bilateral relations with Israel to some degree in the past few years. Egypt has signed contracts to import Israeli natural gas. And Israel and Egypt work cooperatively to keep Hamas in check in the Gaza Strip and Islamic State at bay in the Sinai Peninsula.

The new positive spirit in Egypt’s bilateral relations with Israel is such that Sisi recently invited Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett for talks in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Last week, Egypt’s ambassador to the United Nations condemned Holocaust denial in a speech in the General Assembly, which subsequently passed a resolution on the subject.

The Abraham accords of 2020 also have made a difference. Israel’s normalization agreements with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Sudan have softened Arab attitudes toward Israel, though this process is still in its infancy.

Taken together, these welcome trends explain why the museum decided to mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day in Cairo.

The museum has been cultivating partnerships in the Middle East in an attempt to reach young adults and emerging leaders with information about the Holocaust, which is generally viewed with skepticism in the Arab world.

The most recent event in Cairo is proof that this effort has made headway. Yet there is still some way to go. Not a single Egyptian cabinet minister or official appeared at the ceremony, which is a commentary in itself.

Despite this caveat, we should not lose sight of the fact that International Holocaust Remembrance Day was observed in Egypt. It’s a step in the right direction, and would have been inconceivable only a comparatively short time ago.