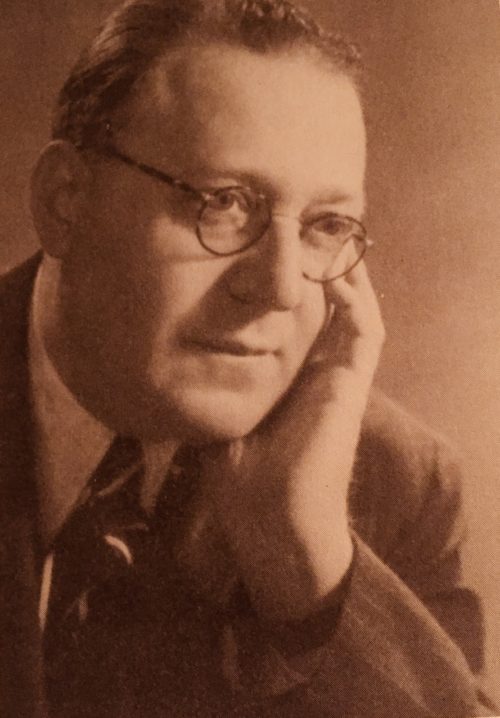

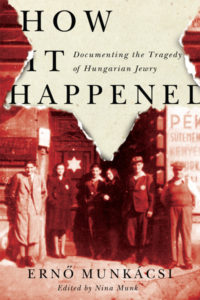

Shortly after the end of World War II, Uj Elet, a Jewish weekly in Budapest, published an article by a Hungarian Jewish lawyer named Erno Munkacsi about the Holocaust in Hungary. Munkacsi had been the secretary of the Nazi-appointed Jewish Council during that dark period. His piece, an agonizing first-hand account of the process that resulted in the deportation of more than 400,000 Jews to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp in Poland, was later expanded into a book, How It Happened: Documenting the Tragedy of Hungarian Jewry.

Munkacsi wrote it as a historical record of the Holocaust in his homeland and as a defence of the Jewish Council, which had been subjected to intense hostility and outrage by survivors. It had been accused of complicity in Nazi crimes, but he believed that a more nuanced version of events was required.

A few years ago, Munkacsi’s first cousin, Peter Munk, a Canadian businessman who died in 2018, found a tattered copy of How It Happened while rummaging through his desk drawers. Having raptly read it in one sitting, he phoned his daughter, Nina, a journalist, to tell her it had to be published in English. The English edition of How It Happened (McGill-Queen’s University Press), edited by Nina Munk, is now available to readers.

Translated from the Hungarian by Peter Baliko Lengyel and annotated by Laszlo Csosz and Ferenc Laczo, it’s a comprehensive, chilling and heart-breaking work. Not surprisingly, it served as a source for Randolph L. Braham’s encyclopedic The Politics of Genocide.

In her preface, Munk contends that How It Happened gives readers “a new understanding of the lamentable, impossible balancing act that (Munkacsi) and his fellow members of the Judenrat performed.” Rather than being heroes, she notes, they were dutiful functionaries who grudgingly complied with Nazi orders in the hope of saving lives. They failed, of course, and How It Happened “illuminates the agony and moral weight of ‘choiceless choices.”’

Munkacsi’s account is preceded by several essays that provide historical context. The fate that befell Jews in Hungary in 1944 is described by Laczo — a professor of history at Maastricht University and the author of Hungarian Jews in the Age of Catastrophe: An Intellectual History, 1929-1948 — in “The Excruciating Dilemmas of Erno Munkacsi.” He offers a jolting reminder that Hungarian Jews, though the last to be affected by the genocidal policy of the Nazis and their local collaborators, had already been under immense pressure prior to Germany’s invasion of Hungary in March 1944.

Let’s review this chronology briefly.

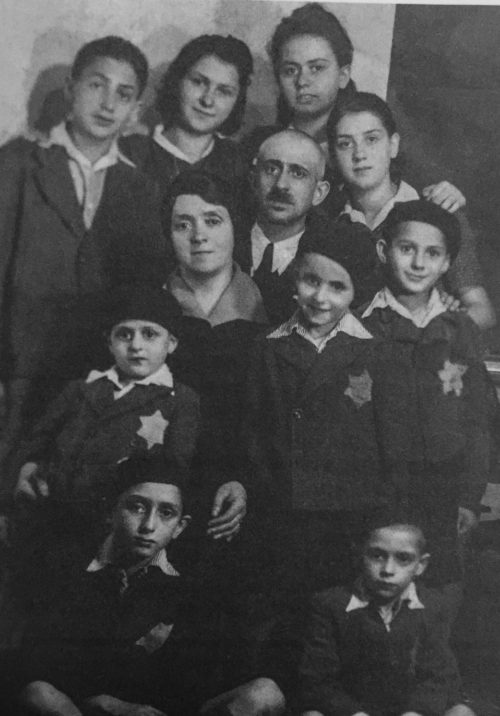

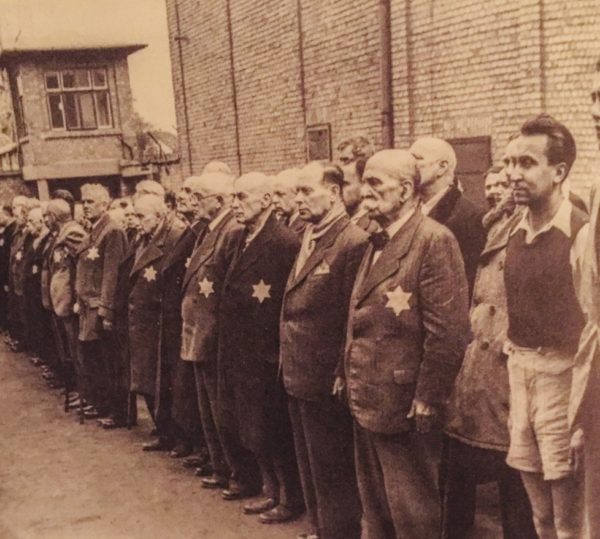

Hungary passed Europe’s first antisemitic numerous clauses law in 1920. Starting in 1938, Hungary annulled the legal equality of its Jewish citizens. Three years later, Hungary, Germany’s ally, adopted Nazi-style laws on “racial protection.” In 1941, Hungary handed over to the Germans almost 20,000 Jews in the recently annexed area of Subcarpathia, where they were murdered. Tens of thousands of Hungarian Jewish men, forced into labor battalions, perished on the Eastern front under appalling conditions.

As Laczo and Csosz point out in another essay, Hungary aligned itself with Germany politically and militarily to avenge the humiliating loss of two-thirds of its territory after World War I. As a result of its alliance with the Germans, Hungary regained about 40 percent of these areas between 1938 and 1941. They were wrested away from Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Romania and Yugoslavia. With these new territories back in its hands, Hungary’s Jewish population swelled from just under 500,000 to more than 700,000.

Hungary paid a heavy price for siding with Germany, losing tens of thousands of its troops in fierce fighting in the Soviet Union. When the Germans got wind of Hungary’s intention to switch sides, Germany occupied the country, setting the stage for the mass murder of its Jewish population in collaboration with the Hungarian fascist government, led by Miklos Horthy and Prime Minister Dome Sztojay.

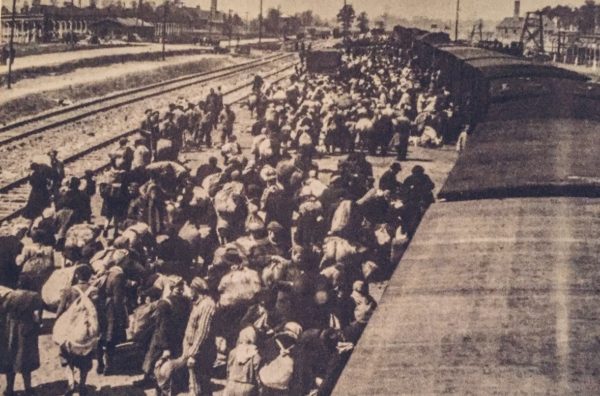

From May 15 to July 9, 437,0000 Jews from outside Budapest who were transported by train to Auschwitz-Birkenau were killed. Hungarian Jews were the single largest group of victims to be murdered in that camp. Horthy, under pressure from the Allies, neutral powers and the Vatican, halted the deportations, leaving around 200,000 Jews in Budapest. With the Arrow Cross takeover in October 1944, they were targeted for destruction. In a matter of months, thousands were shot, deported to various Nazi concentration camps and consigned to death marches.

During this interregnum, Munkacsi and his family went into hiding with the help of Christians, according to Susan Papp, a PhD candidate in the department of history at the University of Toronto. Many members of his family, however, were killed. He died in 1950 at the age of 54.

The Germans established a Jewish Council in Budapest soon after the Wehrmacht rolled into Hungary. Munkacsi, the son of a linguist and ethnographer, was its chief secretary and legal counsel, but its strategy of compliance and petitioning was shaped by its chairman, Samu Stern, and his two deputies, Erno Keto and Karoly Wilhelm. In the eyes of ordinary Jews, they brought the Jewish Council into disrepute by virtue of their strict obedience to German orders and their policy of lulling the Jewish population into submission.

One of the gravest charges levelled against the Jewish Council is that it suppressed the Auschwitz Protocols, a damning report written by Rudolf Vrba and Alfred Wetzler, who escaped from Auschwitz-Birkenau in April 1944. A clinical expose of the full horror of its unprecedented killing procedures, their report reached Hungary and Allied capitals within weeks. In its infinite wisdom, theJewish Council smothered it, reinforcing the misbegotten belief among most Hungarian Jews that they did not face existential danger.

Munkacsi comes down hard on their “infinite naïveté” and “ruinous, unfounded optimism.” But he tempers his critique by calling attention to the Germans’ “devilish cunning and unscrupulous hypocrisy.” As he puts it, “The idea was to lure the Jews into a trap slowly, step by step, treating them kindly at first, then stepping up the cruelty until they reached the gas chambers of Auschwitz.”

He adds that Jews deceived themselves by clinging to the misconceived assumption that the Hungarian state would not betray its Jewish citizens. But as he bitterly admits, Hungary left them to the tender mercies of the Germans.

The Jewish Council received its marching orders one morning as Gestapo officers clad in leather coats and carrying submachine guns turned up at its headquarters. In exchange for unconditional obedience, no harm would come to Jews, the council members were sternly told. Some Jews fell for the lie completely. “Everything is all right here,” Munkacsi quotes one Jewish elder as saying. “The Germans still want to help us.”

The top-ranking German officials who organized the mass deportation of Jews from Hungary to Poland were Adolf Eichmann, who claimed he was born in Palestine and could speak Hebrew; Hermann Krumey, who exhibited fleeting signs of humanity, and Dieter Wisliceny, an almost jovial figure who loved women, liquor and money.

Eichmann let it be known that Jews would live under restrictions for only the duration of the war. “He declares himself not to be a friend of violence in general, and wishes that things could be taken care of peacefully,” Munkacsi writes.

In the early spring, “most disturbing” reports from the provinces indicated that deportations had begun. Council leaders rushed to the Ministry of Interior to speak to the minister, Laszlo Endre. When they arrived, Endre brushed them off and, gloves in hand, left abruptly. The Jewish visitors then turned to Endre’s secretary for information, but he callously denied the terrifying news.

“Incredible as it may sound today, it is a telling fact … that, before the second half of May 1944, Hungarian Jewry had no idea of the horrors of the extermination camps or the details of the deportations,” says Munkacsi in a devastating commentary on their gross ignorance. “Jews buried their heads in the sand, convincing themselves that whatever they could not see did not exist … The few who had the foresight were accused of defeatism.”

As news of the deportations spread, the “naked truth” sunk in: “the Gestapo, aided and abetted by the Gendarmerie and the Hungarian authorities, had decided on the wholesale deportation of Hungarian Jews.”

According to Munkacsi, the “first ringing bell directly warning us of the annihilation” rang out when Fulop Freudiger, head of an Orthodox synagogue in Pozsony, issued a warning that the Germans had completed all the necessary preparations for the deportations. Freudiger’s “bombshell” meant that “time was up and that the death knells had tolled for Hungarian Jewry.”

Munkacsi, in a reference to the Vrba-Wetzler report, goes on to say, “We only had to wait a few more days for even more dreadful news. Since 1942, they had witnessed the extermination of Jews from Poland, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and, finally, from Greece and Italy.”

With the Gestapo “massively understaffed” in Hungary, the Germans would not have been able “to carry out the deportations from the provinces without the assistance” of the Hungarian police, he says in a scathing indictment of Hungary’s antisemitic regime. Realizing that time was of essence before Jews awoke from their torpor, the Germans proceeded to deport Jews at “breakneck speed.”

The censored Hungarian media was forbidden to cover the deportations. “The official Jewish press confined itself to spoon feeding reassuring news,” he says contemptuously. Jews in Budapest with families in the provinces received letters from frightened relatives, prompting them to bombard the Jewish Council with demands for “action and tangible results.” It replied it was doing “everything humanly possible” to avert deportations.

The Catholic Church, having approved of Hungary’s anti-Jewish laws, stood by with folded arms as Jews were sent to their deaths in Poland. The Catholic primate, Jusztinian Seredi, delivered a speech in Parliament in which he justified the need to “curb the presence of Jews in public affairs, the economy, and other areas of life …” The Calvinist church, though, condemned the deportations as a violation of “human dignity, justice and charity.”

Horthy, a vicious antisemite, had prior knowledge of the deportations, Munkacsi charges. His son was supposedly shocked by the news and promised the Jewish Council to relay this information to his father. Munkacsi believes that Horthy stopped the deportations only after the first Allied daytime bombing of Budapest, an event that convinced the government that the Allies were winning the war. Munkacsi lauds the role that Raoul Wallenberg — a Swedish businessman-turned-diplomat based in Budapest — played in the cancellation of the deportations.

He is of the view that the Hungarian officials most responsible for the deportations were Laszlo Ferenczy, the commander of the police units charged with rounding up Jews; Laszlo Endre, the minister of interior, and his colleague, Laszlo Baky.

Another figure who facilitated the deportations was Imre Finta, the Gendarmerie commander in Szeged who corralled 9,000 Jews into a brickyard on the outskirts of the city and herded them into boxcars headed for Auschwitz-Birkenau. After the war, Finta immigrated to Canada and opened a restaurant. In 1987, he became the first person in Canada to be prosecuted under its war crimes law.

In a description of the predicament of Jews in Budapest, Munkacsi says they were huddled together in 1,900 designated buildings and subjected to a host of debilitating restrictions, particularly after the Arrow Cross assumed power on October 16, 1944. It was a day “without a trace of sun, heavy with darkness and gloom,” he writes. “Stunned Jews gasped under heavy blows as the takeover was celebrated with piercing cries of debauchery, cheering and vengeance. The streets of Budapest opened wide to the pogrom-mongering armies, fulfilling the pipe dreams the villains had nourished for months, years and decades.”

On this somber note, Munkacsi’s bleak portrayal of the “last chapter” of the Holocaust draws to a fearful close.