Have you ever heard of Karl Landsteiner? Paul Ehrlich? Or Rosalind Franklin?

If these names don’t ring a bell, you can read all about them in British writer Norman Lebrecht’s informative book, Genius & Anxiety: How Jews Changed the World, 1847-1947 (Scribner).

Landsteiner, one of the first immunologists, made modern surgery possible by developing a method for testing different blood types. Ehrlich was the father of chemotherapy. Franklin was instrumental in mapping out our DNA system.

Lebrecht does not claim that Jews are exceptional or genetically gifted, but believes that adversity shaped them. “The composer Gustav Mahler was fond of saying: ‘A Jew is like a man with a short arm. He has to swim harder to reach the shore.’ Anxiety acts on them like an Egyptian taskmaster in the book of Exodus. It goads them to acts of genius.”

Regardless of whether you agree with Lebrecht’s theory, the fact remains that Jews have made immense contributions in different fields. If you’re still skeptical, consider the disproportionate number of Jewish Nobel Prize winners.

I’m not sure why Lebrecht chose 1847 and 1947 as bookends. He claims they delineate an era in which Jews “engaged more intensely with the rest of the world than at any other time.” I’m not convinced he’s entirely right, but there it is. Genius & Anxiety tells a crackling good story.

One of Lebrecht’s first geniuses is the political philosopher Karl Marx, whose theories jolted and upended societies. A convert to Christianity, he believed Jews should have equal rights after they had abandoned Judaism. He set out his argument in the essay On The Jewish Question. “This stew of wild generalizations and blind prejudice is textbook antisemitism: get rid of the Jews and all will be well with the world,” writes Lebrecht.

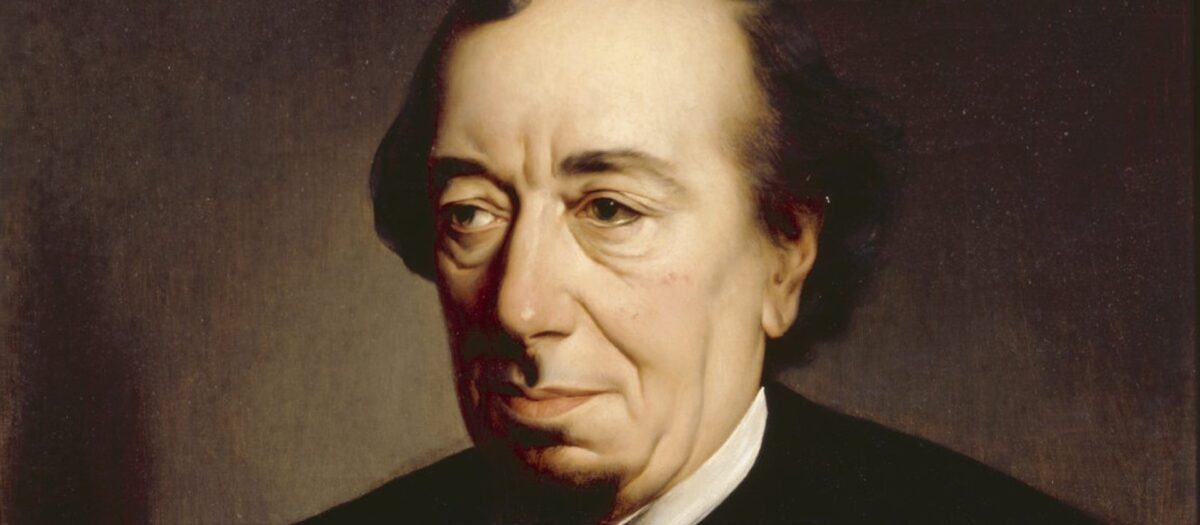

Benjamin Disraeli, the first British prime minister of Jewish descent, was a convert, too. Although he was raised in the Church of England and loved its hymns, he remained “defiantly Jewish.” Insulted in Parliament as “a lineal descendant of the blasphemous robber,” Disraeli replied, “Yes, I am a Jew. And when the ancestors of the Right Honorable gentlemen were brutal savages in an unknown island, mine were priests in the temple of Solomon.”

To Disraeli, Jews represented everything he desired for Britain: entrepreneurial, restless, quizzical, cultured, philanthropic, productive, contentious and colorful.

Lebrecht skips ahead to Siegfried Liepmann Marcus, who constructed an internal combustion engine and set it on a four-wheeled cart. He had seen the future. Marcus’ contraption predated Daimler and Benz by a decade and Henry Ford by 25 years. Until the Nazis erased his name from the record, he was known across central Europe as the inventor of the automobile.

Sarah Bernhardt, born Jewish to a high-class prostitute and baptized on the insistence of her mother’s lover, was a stage performer like no other. According to Lebrecht, she was “the prime inventor” of our cult of celebrity, “the first person to grasp the meaning of soft power and its manipulation.”

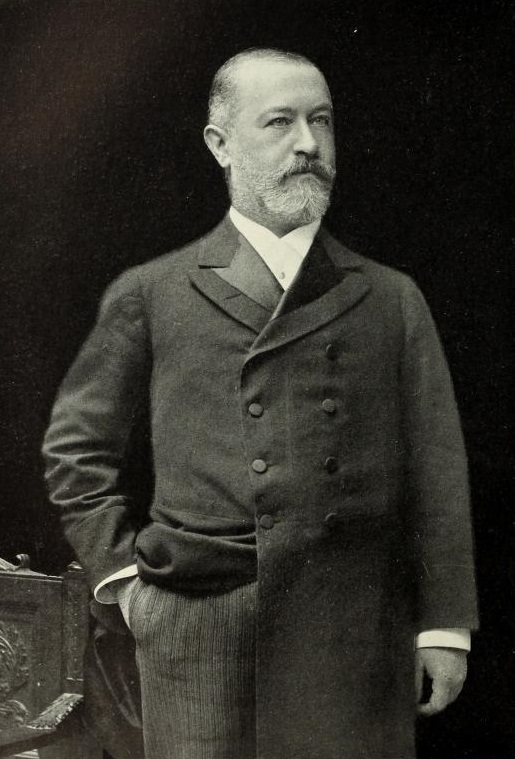

Jacob Schiff, descended from a rabbinic dynasty, was a game changer who became a merchant banker in an expanding industrial economy. He ascribed his analytical skills to Jewish learning.

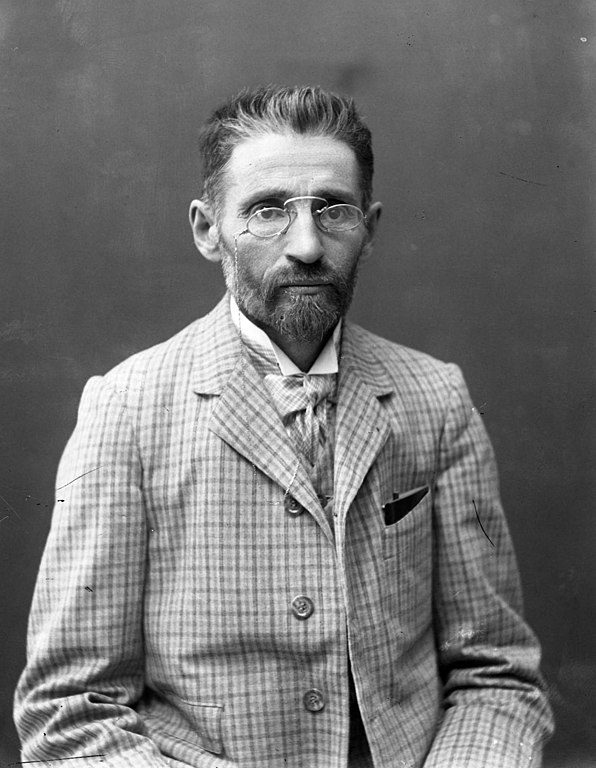

Eliezer Perlman, who would change his surname to Ben-Yehuda upon settling in Ottoman Palestine, revived Hebrew. He died in Jerusalem in 1923, a quarter of a century before the birth of Israel. Nearly 100 years later, nearly ten million Israelis speak the language he refined and adapted for modern living.

Theodor Herzl was a Viennese journalist who covered the trial of Alfred Dreyfus, the French Jewish artillery officer accused of treason. Shocked by the outpourings of antisemitism, he repudiated assimilation, turned inward and founded the Zionist movement, a watershed moment in the Middle East.

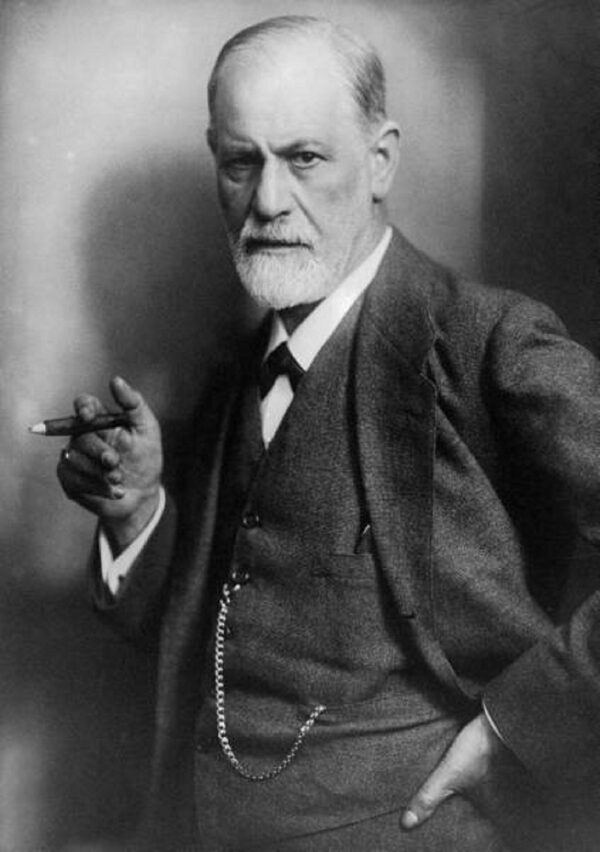

Sigmund Freud, the psychoanalyst, was a non-entity at the age of 40, but obscurity would soon give way to fame. “More books have been written about Freud than any other person of his time,” says Lebrecht. “Most, even those by enemies, acknowledge him as a historic personality … His ideas infiltrate every niche of society, arts and scholarship.”

Albert Einstein, the physicist, created the best-known formula in the history of science — E=mc2, the Theory of Relativity.

Irving Berlin composed the unofficial American anthem, God Bless America, and two sings, White Christmas and Easter Parade, which rebranded two religious holidays for mass consumption. Altogether, 1,500 songs bear his signature.

Samuel Goldwyn, Louis B. Mayer and Jack Warner were among the moguls who built the Hollywood film industry. David Sarnoff and William Paley founded the NBC and CBS radio networks.

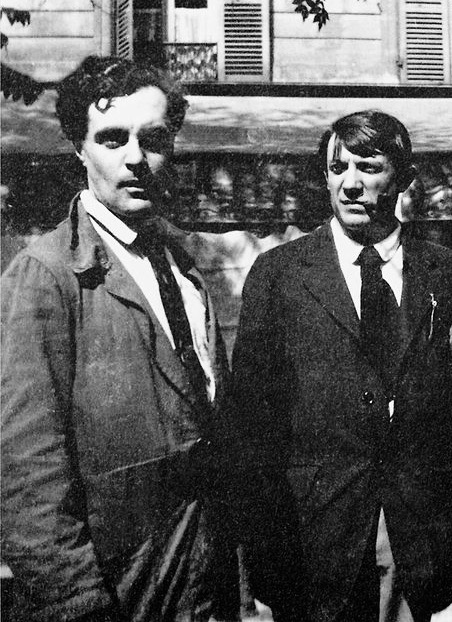

Amedeo Modigliani, the painter who lavished attention on the female form, was the first Jew in two millennia to stand in the forefront of the art world.

Leon Trotsky, a stellar figure of the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, turned the Red Army into a formidable force. Expelled from the Communist Party and the Soviet Union by his arch rival, Joseph Stalin, he went into exile in Turkey, France and Norway before settling in Mexico. He was assassinated by a Stalinist agent in 1940.

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster created Superman, the first comic book hero. Bob Kane and Bill Finger concocted Batman, the second all-American super hero.

Of course, Genius & Anxiety is filled with many more names. It is truly encyclopedic in scope.

Given the upsurge of antisemitism of late, Lebrecht is of the view that the age-old Jewish Questions has been reopened. “The sense of otherness is back,” he says. “Jews, we are told, are different. As the anxiety rises, so, too, does the flood of invention. This story is not over yet.”