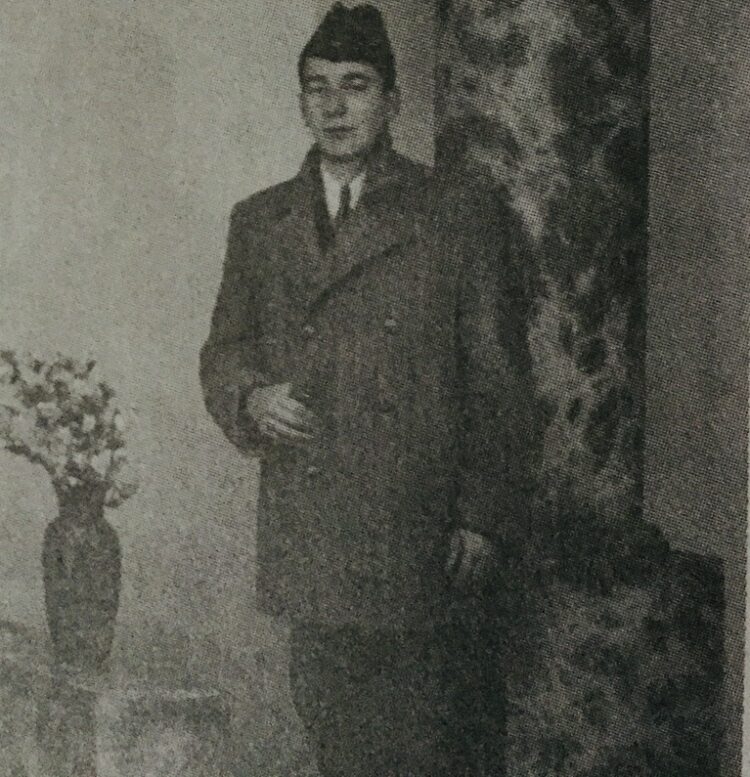

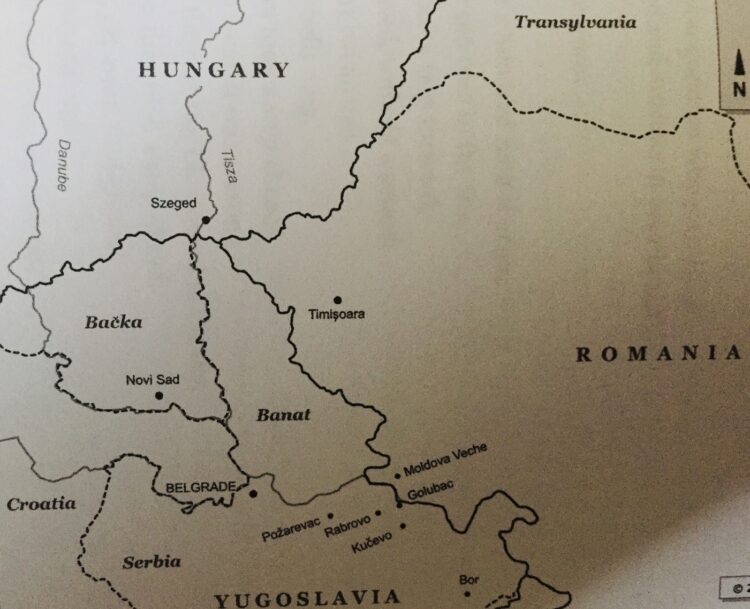

Ferenc Andai, a Hungarian Jew, was plunged into purgatory on May 16, 1944, when he was press-ganged into fascist Hungary’s forced labor service. He was only 19 when, along with 6,000 other Hungarians, mostly Jews, he was consigned to a copper mine in Bor, a town in Nazi-occupied Serbia.

For the next four months, he was subjected to unbridled mistreatment and terror. Having survived this crushing ordeal, he returned to Hungary, where he resumed his studies and worked as a journalist. In 1957, following the unsuccessful Hungarian uprising, he immigrated to Canada.

Andai’s memoirs, published in Hungary in 2003 under the title of To Bear Witness: A Story of Bor, won the Miklos Radnoti National Prize. It is named after a Jewish-born poet whom Andai met in Bor and who was subsequently murdered.

The English-language version, In The Hour of Fate and Danger, has been published by the Azrieli Foundation. This heart-felt volume is not only a chronicle of resilience and survival. The introduction, by Israeli historian Robert Rozett, is a blow-by-blow account of Hungary’s forced labor service, which swallowed up about 100,000 Jewish men.

Seventy thousand of them were sent to the eastern front in the Soviet Union to clear minefields and perform back-breaking work for the Hungarian army, which fought alongside Germany’s Wehrmacht. Eighty percent of these hapless laborers died, the victims of severe hunger, rampant disease and accidents.

The first Hungarian workers were sent to Bor in 1943, when the Germans increased production in the copper mines. Germany acquired the mines after invading what was then Yugoslavia. Managed by the Siemens conglomerate and the Todt organization, they were strategically important for Germany’s war effort, copper being a vital material in the manufacture of airplanes, tanks, rifles, machine guns, cannon balls and cartridges.

Andai, whose original surname was Goldberger, was born in Budapest in 1925. When he was conscripted into the labor service, Hungary had been occupied by Germany for two months and the antisemitic Hungarian government had begun deporting Jews to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp, where more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews were murdered.

En route to Bor, he spent five suffocating days in a stinking cattle car. Once there, sadistic Hungarian guards hurled vile curses at him and his fellow prisoners. The camp in which they toiled was infested with filth and vermin.

“We received low-calorie food,” he writes. “In the morning, a murky black liquid and German army bread, the taste and texture of sawdust, decorated with greenish-grey mould, a quarter of a kilo for a whole day. At noon and in the evening, a thin soup with cabbage, every now and then enriched by tiny bits of potato. Dangerously little for physical labor in the mountain air.”

Allied warplanes flying overhead fed their hopes for an imminent Allied victory in the war. “We keep counting the airplanes, anxiously rooting for their success, and when they return intact we heave a sigh of relief.”

They were also buoyed by news of Romania’s withdrawal from its alliance with Germany and the Red Army’s advance toward Hungary.

They yearned to escape, but feared reprisals. “We’ve been told many times that if someone flees, their nearest barracks mate will be executed right away.”

The Germans, having evacuated Bor in September of 1944 after a succession of Allied victories, marched thousands of prisoners out of the camp. Conditions were horrible. “Our empty stomachs enervate us,” Andai says. “Thirst drives us mad. Our mess tins are empty … the rain is falling incessantly, and we slip and slide on the bumpy, winding road.”

Andai was eventually liberated by pro-Soviet partisans, but the Germans had still not been defeated. During this interregnum, he was consumed by unsettling memories. “These past few months, everything in my life has gone terribly wrong. I was driven out of my hometown, Budapest. I was auctioned off as a slave for a few crumbs of copper because I had become a burden on my nation. We were shackled together and thrown to the frenzied murderers, like the gladiators to the tigers in the Roman arena.”

Much to his shock, the Germans regrouped and launched an offensive, but were driven back. In Hungary, the pro-German government switched sides, prompting Ferenc Szalasi’s murderous Arrow Cross movement to assume power. “The horrendous news paralyzes us,” says Andai. “I am stricken to the depths of my soul.” Nonetheless, Andai continued his trip back to Hungary, his body crawling with lice and fleas.

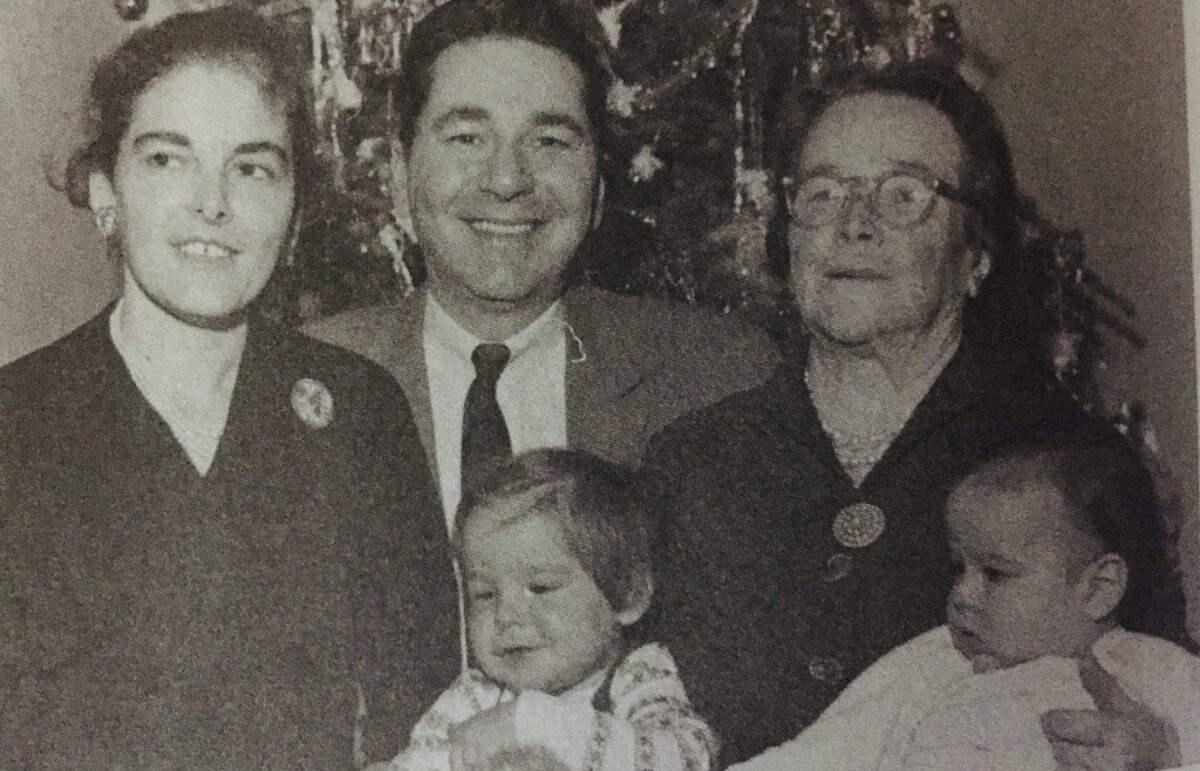

He reached Budapest in April 1945 and was reunited with his widowed mother and older married sister. After obtaining a university degree in history, he landed a position as a journalist on a newspaper, where he met his wife-to-be, a photographer. Shortly after their marriage, they decided to leave communist-ruled Hungary.

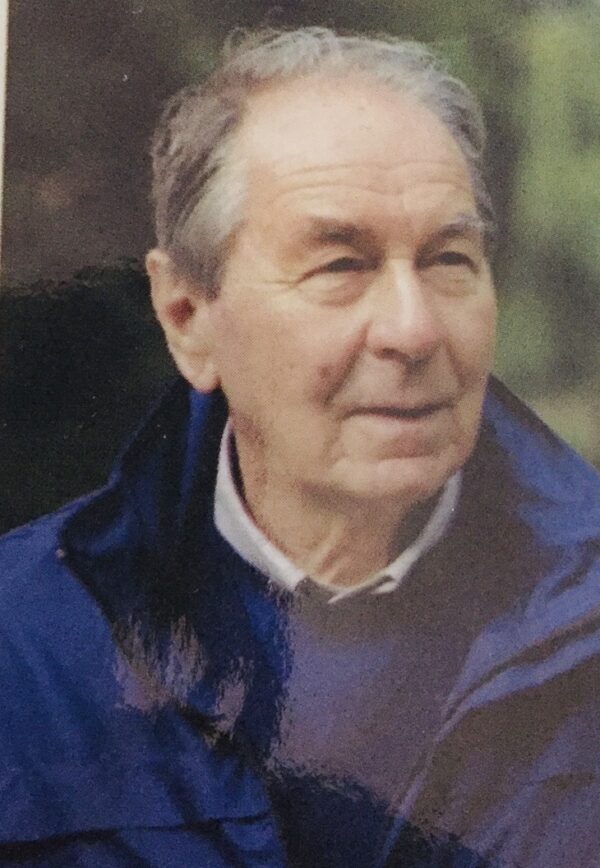

Andai’s first years in Canada were difficult, but he settled down after finding a job as a history teacher at a high school in Shawville, Quebec. “My father remained very connected to Budapest, to where he returned almost every year to visit family and friends,” writes his daughter, Diana, in the afterword.

In 2005, he returned to Bor to appear in a documentary about Miklos Radnoti. Watching the film, Diana paused it momentarily. She writes, “I studied my father’s face and wondered how he was able to return … and confront this site of former horror so calmly. I wondered what emotions he felt as he knelt down to pick wildflowers growing where there was once a slave labor camp … I have no doubt my father would have said that this is history and our story to tell if we and future generations are to keep learning.”

Andai’s memoir is indeed a cautionary tale about the thin veneer of Western civilization.