The rescue of Jews in Nazi-occupied countries is an oft-repeated story in Holocaust literature. Max Wallace’s impassioned book, In The Name of Humanity: The Secret Deal To End The Holocaust (Penguin Random House), is the latest addition to that list.

Wallace focuses on the efforts of three Swiss nationals, a Swedish-based German Jew and a Finnish masseur to alleviate the plight of Jews before and during World War II.

The rescuers were Recha Sternbuch, a Polish Jew who immigrated to Switzerland with her husband in 1928; Jean-Marie Musy, Switzerland’s former president; Norbert Masur, a German citizen who acquired Swedish citizenship in 1921 and served as the World Jewish Congress’ representative in Stockholm; Felix Kersten, a masseur from Finland who moved to Sweden in 1943 and frequently travelled to Germany to ease the abdominal pain of SS leader Heinrich Himmler, one of the architects of the mass murder of European Jews, and Saly Mayer, a retired knitwear and lace manufacturer and the president of the Union of Swiss Jewish Communities.

Sternbuch and her spouse, Isaac, were ultra-Orthodox Jews who lived in St. Gallen, a picture postcard town nestled between Lake Constance and the snowcapped mountains of the Appenzell Alps.

From 1933 to 1937, upwards of 6,000 Jewish refugees were admitted into Switzerland. Hundreds them acquired temporary housing thanks to Sternbuch. She was assisted by the commander of St. Gallen’s police force, Paul Gruninger, who was charged with criminal offences and relieved of his duties in 1939.

Sternbuch’s bete noire was Heinrich Rothmund, the head of the Swiss Alien Police, who convinced the Swiss government to turn away German Jews and return them to Germany. In coordination with Switzerland, the Nazi regime began to stamp the passports of German Jews with the letter J to make it easier for Swiss border guards to reject refugees.

Shortly after Gruninger’s dismissal, the Swiss government accused Sternbuch of illegally smuggling refugees into the country. A judge dismissed the case, citing a lack of evidence. In 1940, the Sternbuchs and their three children left St. Gallen and moved to the scenic Swiss city of Montreux so that their eldest son could attend a yeshiva.

From her base in Montreux, Sternbuch obtained more than 2,500 passports from the embassies of Paraguay, Honduras and El Salvador, thereby saving live in the Warsaw ghetto. She also secured 250 entry certificates for Palestine, a British colony. After Germany’s invasion of Hungary in 1944, she lobbied on behalf of Hungarian Jews, demanding that the War Refugee Board in the United States intervene to stop their deportation to the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp.

Sternbuch received assistance from Julius Kuhl, a Polish Jew who had studied in Switzerland and worked in Poland’s embassy in Bern as a special assistant for Jewish affairs under the direction of the ambassador, Alexander Lados. In particular, Kuhl helped Sternbuch facilitate the shipment of food packages to religious Jews trapped in Warsaw’s Nazi ghetto.

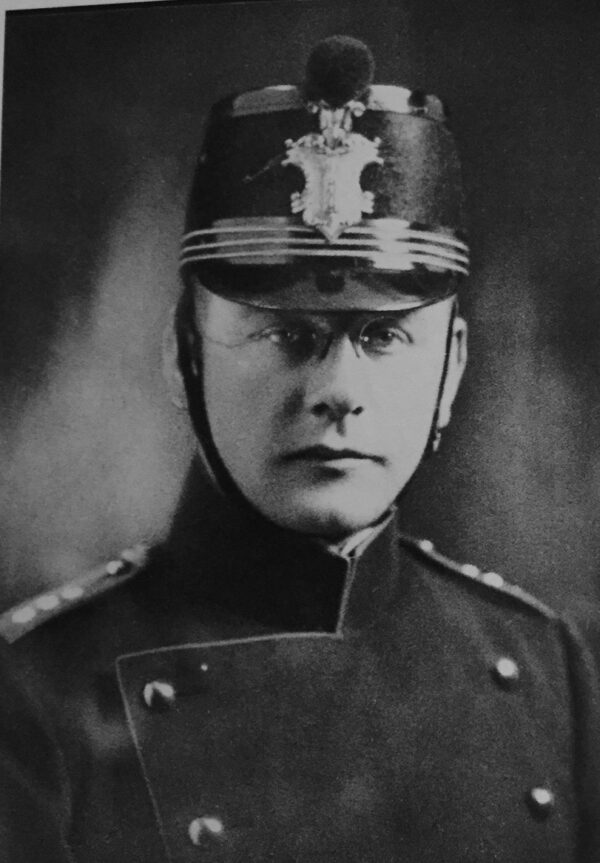

In a bold gambit, Sternbuch approached Musy, who stepped down as Swiss president in 1934. A fierce anti-Communist who was partial to Nazi Germany and on friendly terms with some of its leaders, including Himmler, he was nonetheless appalled by the Holocaust.

At Sternbuch’s behest, Musy arranged a meeting with Himmler in 1944 in Germany. Asked what it would take to slam the brakes on its exterminationist policy, Himmler replied that Germany was a desperately short of trucks, machinery, tractors and drugs. In exchange for these products, he would be willing to free some Jews, including Sternbuch’s relatives.

In what was clearly a deception, Musy told Himmler that the Allies would be open to a compromise peace agreement with Germany if it eased up on its anti-Jewish policy.

Wallace believes that Musy’s negotiations with Himmler were helpful in persuading the Nazi regime to blow up a crematoria in Auschwitz on November 25, 1944 and in allowing relief packages and a Red Cross presence in concentration camps during the final weeks of the war.

In one of the most bizarre episodes of the war, Masur, a German Jew, secretly flew to Germany on April 20, 1945 to meet Himmler. The meeting took place in Kersten’s home near Berlin. Himmler launched into a rant, saying that Jews were an “alien element” in German society, that Germany was a bulwark against Bolshevism, and that Hitler would be remembered as a great man.

Despite his diatribe, Himmler agreed to release one thousand Jewish women from the Ravensbruck concentration camp and promised that no further death marches of Jews would occur.

Before the war, Mayer was instrumental in financing the care and feeding of Jewish refugees who had poured into Switzerland. During the final months of the war, he met German officials, convincing them to allow 318 Jews to leave the Bergen-Belsen camp for Switzerland.

In summing up, Wallace writes that while much of the world abandoned Jews to their fate during the Holocaust, “a small disparate group came together to rescue the remnants of European Jewry.”

They could not, of course, stem the tide of Nazi genocide, but their humanitarian rescue work saved lives.