Land , land! — This is the secret to the solution of the Jewish question, the Zionist ideologue Nathan Birnbaum wrote in 1893. While Zionists like Birnbaum regarded Palestine as a panacea for Jewish homelessness and the threat of antisemitism, territorialists looked elsewhere around the globe to resolve the problems that plagued Jews in the Diaspora.

In his rigorously-researched and lucidly-written book, In the Shadow of Zion: Promised Lands Before Israel (New York University Press), Adam Rovner delves into six potential Jewish homelands that might have offered Jews a measure of territorial independence.

Rovner, an associate professor of English and Jewish literature at the University of Denver, examines these “lost visions of Jewish autonomy” in New York state, East Africa, Angola, Madagascar, Tasmania and British and Dutch Guiana. The now obscure figures who worked on these failed projects, he observes, found themselves caught up in a tangle of utopian fervor, feverish diplomacy and geographic exploration.

Before he plunges head-long into his narrative, Rovner lists the ideological principles that Zionism and territorialism shared.

“Both movements were dedicated to establishing a territorial entity under Jewish control through political means and the process of mass settlement, to a revival of Jewish social, and cultural existence through demographic concentration and physical labor, and to a renaissance of national identity through the perpetuation of Jewish language and creative endeavor,” hewrites in the introduction.

Zionism and territorialism diverged on a number of points, he adds. “They differed, above all, in where that territorial entity should be founded, what forms Jewish socio-cultural life should take, and what language best expressed Jewish national identity.”

Territorialists rejected Palestine as a destination of mass Jewish settlement, belittling the Zionist hypothesis that its Arab inhabitants would obligingly leave, and championed Yiddish rather than Hebrew.

Despite their differences, Rovner points out, territorialists and Zionists both created formal membership organizations, held international congresses, launched periodicals to disseminate their views, attracted notable intellectuals to their cause and negotiated with world politicians.

The territorial projects he highights were initiated and supported by Jewish individuals or organizations, aspired to sovereignty or a high degree of autonomy and received the imprimatur of government consent. In light of these criteria, Rovner leaves out the Jewish Autonomous Region in Siberia (Birobidzhan) from his discussion.

The two major outfits dedicated to a Jewish homeland outside Palestine were Israel Zangwill’s Jewish Territorial Organization and its successor body, the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization. The latter was headed by Isaac Nachman Steinberg, an editor, author and former Soviet commissar for justice who, though not hostile to Zionism, was a critic of the Jewish community in Palestine. He was uncomfortable with its militarism, rejection of Diaspora life and denigration of Yiddish.

Long before Zangwill and Steinberg appeared on the scene, Mordecai Manuel Noah, an American Jew, became “the first Jew in the modern world to advance a practical program for Jewish territorial concentration.”

A journalist, diplomat and playwright, Noah devised a scheme in the first quarter of the 19th century to purchase an island on the Niagara River as a sanctuary for persecuted European Jews. Grand Island, about 20 percent larger than Manhattan and rich in timber resources, had been bought by New York state from the Seneca Indians. Noah’s intention was to build a city there under the auspices and protection of the United States. It would be known as Ararat.

Having recognized Noah’s request, the state assembly formed a committee to study his proposal. Lawmakers, however, expressed opposition to selling the island to Noah, who never set foot on it. They argued that Jews ought “to mix with Christians, and not live alone” in a separatist colony.

The American Jewish response was similarly negative, with one prominent rabbi claiming that the restoration of Jewish nationhood could only achieved after the dawn of the messianic era.

As Rovner observes, the founder of modern political Zionism, Theodor Herzl, considered a number of places — Uganda, Argentina, Cyprus, Mesopotamia, Mozambique and the Sinai Peninsula — before settling on Palestine as the focus of Zionist yearning.

Uganda, in particular, appealed to the highest echelons in the Zionist leadership, including Eliezer Ben Yehuda, who resurrected Hebrew as a spoken language in Palestine.

When British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain received Herzl, he said, “I have seen a land for you on my travels, and that’s Uganda.” Chamberlain’s offer was cloaked in ulterior motives. A substantial colony of Jews in East Africa could pose an obstacle to German expansionism, Britain figured.

The Zionist movement eventually rejected Uganda as the new Zion, but the territorialists were keen. Britain earmarked a place called Uasin Gishu for Jewish colonization. Remote and unexplored, it was about the size of the U.S. states of Connecticut and Rhode Island. But for reasons Rovner cites, East Africa failed to morph into a magnet for Jews.

Angola, a Portuguese colony, surfaced as a possible venue for a Jewish homeland when the Jewish Territorial Organization received a letter from a Russian-born Jewish civil servant in 1912 claiming that the Benguela Plateau in Angola’s highlands could support a thriving settlement.

After much discussion, a team of experts was dispatched to Angola to survey the terrain. They concluded that the plateau, one of Angola’s richest agricultural zones today, was decidedly superior to that of Palestine, and that crops like coffee, oranges, bananas and corn could flourish there.

The Portuguese themselves were divided over the matter. Some politicians were of the opinion that Jews would be a Fifth Column serving the interests of Britain and Germany. Still others believed that Portugal stood to gain financially from their presence.

The project fizzled when Jewish funds ran low and both chambers of Portugal’s parliament failed to take a final vote on the plan.

Daniel Defoe, the author of Robinson Crusoe (1719), helped popularize the notion that the inhabitants of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar were the descendants of the lost tribes of Israel. But it was not until 1936 that the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization adopted the notion of settling Jews on the island, a French colonial possession.

France’s colonial minister, Marius Moutet, publicly announced he was “very sympathetic to the idea of the eventual establishment of Jews in our colonies.” Some hailed his statement as a French version of the 1917 Balfour Declaration, Rovner notes.

Vladimir Jabotinsky, the Zionist Revisionist leader, supposedly told Poland’s foreign minister, Jozef Beck, that Madagascar, along with Palestine, could absorb countless Polish Jews. Poles like Beck hoped to solve the so-called Jewish question through emigration.

As Rovner suggests, antisemites have gravitated toward Madagascar since 1885, when the German scholar/Jew-hater Paul de Lagarde called for the expulsion of German Jews to the island.

In 1937, a three-man commission visited Madagascar and returned with a relatively positive report of its possibilities. No action was taken, and the plan died on the drawing board.

Perversely enough, Nazi Germany revived it in 1940, pursuing it until 1942. In the eyes of the Nazis, Madagascar would be converted into a super ghetto for European Jews. The plan was endorsed by Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, and Adolf Hitler, but it was never implemented following Britain’s invasion of the island.

Rovner credits Melech Ravitch, a major literary figure in inter-war Poland, with having ignited interest in mass Jewish immigration to Australia. With the intensification of antisemitism in Poland, Ravitch lost faith in a Jewish future in Europe. Visiting Australia in 1933, he imagined it to be a nation flowing with milk and honey.

The Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization had already expressed an interest in Australia. By the early 1940s, Steinberg, its chief visionary, was in touch with an Australian Judeophile, Critchley Parker Jr., over bringing Jews to Australia. The scion of a wealthy entrepreneur, Parker was convinced that the island of Tasmania, with its vast forests, rich fishing waters and untapped mineral wealth, could become the “new Jerusalem” for the “Jewish homeless who seek a land.”

Yet Tasmania, as Rovner exhaustively elucidates, proved to be yet another flash in the pan with respect to Jewish resettlement.

In the penultimate chapter, “Welcome to the Jungle,” perhaps Rovner’s best, he deals with two of the remotest destinations — British and Dutch Guiana, which are largely covered by impenetrable rainforests.

British Guiana, following Kristallnacht in Germany in 1938, caught the attention of The New York Times. The newspaper reported that Britain was ready to allow 50,000 Jews to immigrate to the South American colony, but warned that immigrants would have to contend with venomous snakes and voracious caimans.

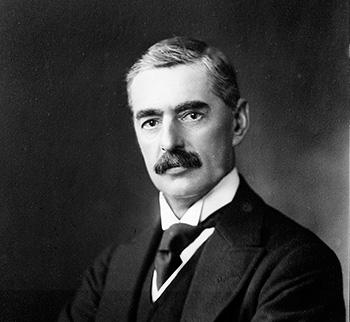

Britain’s prime minister, Neville Chamberlain, had told the House of Commons that British Guiana contained “extensive tracts of sparsely occupied land” that might be suitable for Jewish settlement. Chaim Weizmann, the president of the World Zionist Organization, begged to differ, warning that such underdeveloped territories “cannot satisfy the dire and immediate need of German Jews.”

A commission was sent to British Guiana to study the lay of the land. Its members were ambivalent. While conceding it was not an ideal place for refugees, they saw possibilities for massive settlement. Rovner suggests that Chamberlain’s offer was disengenuous. He dismisses it “a sop to Jewish organizations … to divert Zionist criticism from the pending white paper, which was to limit Jewish immigration to Palestine …”

Since no significant funds were available for an undertaking of this magnitude, the British Guiana proposal also expired.

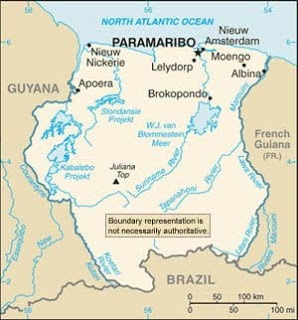

Rovner, in much of this exotically flavored chapter, focuses on Suriname (Dutch Guiana), which has had a Jewish community for centuries. “Documents trace an unbroken Jewish presence here back to at least 1643,” he writes in reference to the capital, Paramaribo. “By the middle of the next century, Jews made up more than one-half of (its) white population.”

Under the sway of the Dutch, he notes, many of the Jews in Suriname became wealthy merchants. By one estimate, Jews owned one-quarter of its African slaves. Still other Jews were peasant farmers, plantation owners, soldiers, doctors and shopkeepers. And they enjoyed civic freedoms unknown to Jews elsewhere.

In an epoch when Jews were crammed into ghettos and forbidden to own land, the Jewish inhabitants of Suriname constructed a thriving agrarian settlement, Jodensavanne, about 40 miles upriver from Paramaribo. It lasted for about a century, until the sugar market tumbled and a series of slave revolts erupted.

With race mixing common in Suriname, Jews frequently married gentiles, whites and blacks alike. In passing, Rovner mentions Cynthia McLeod, the daughter of independent Suriname’s first president, Johann Ferrier, and an author in her own right. Of partial Jewish descent, she told Rovner, “Every Surinamese has Jewish blood. Shake a family tree and a Jew falls out.”

Cognizant of Suriname’s long connection with Jews, the International Refugee Colonization Society dispatched a commission to investigate the suitability of Jewish resettlement there. The year was 1939. As a result of the outbreak of World War II, the plan was shelved. But after 1945, the Freeland League for Jewish Territorial Colonization promoted Jewish settlement in Suriname.

Its efforts gained the financial support of American notables like the Hollywood director George Cukor, the screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz, the cosmetics magnate Max Firestein and the trade union leader David Dubinsky. Thomas Mann, the German novelist, supported its activities as well.

A commission of experts surveyed the Saramacca district as a possible site for a Jewish colony. Offering advantages ranging from a fine climate to fertile soil and an ample water supply, it was two-thirds the size of Rhode Island. Regarding it as a latter-day Jodensavanne, the commissioners thought it could be self-sustaining through the export of sugar.

For a while, the Saramacca proposal seemed promising, but due to opposition from the Zionist movement, it never really got off the ground. And so it withered, like all the previous misbegotten notions to build a Jewish homeland outside the framework of Zionism.