I‘ve read The New York Times for many years now and consider it a great newspaper. Daniel Schwartz, the author of End Times? Crises and Turmoil at The New York Times (State University of New York Press), concurs. “I believe the Times is still the best and most influential newspaper in the world,” he writes in this deeply-researched and informative book.

Schwartz, an English professor at Cornell University, is impressed by the Times for a number of reasons. The Times, with 24 news bureaus abroad, excels in foreign coverage. Its reporting of domestic and cultural affairs is first-rate. Its weekly science and food sections leave little unturned.

And yet, in common with the entire newspaper industry in North America, once a reliable cash cow, it has experienced declining circulation and advertising.

The crisis facing the Times stems, in large part, from the rapid expansion of the Internet, the proliferation 0f on-line publications and the rise of cable television, all of which have challenged the Times‘ relevance as a major source of news.

Responding to these formidable challenges, the Times has poured enormous resources into its digital edition and erected a paywall, a strategy that has paid off. As of a few years ago, the Times‘ website reached over 20 million unique visitors per month, while the print edition reached 2.9 million readers Monday through Friday and four million on Sunday.

Nonetheless, Schwartz says, the Times is still struggling to make its website economically viable in terms of attracting sufficient advertising revenue, this at a time when people are reading less.

Although he admires the Times, Schwartz is hardly a cheerleader. He points out that it no longer covers as many countries with its own correspondents as in the past. And he thinks that the glossy Sunday magazine is struggling for identity and readership, and that the Book Review is far less important than it was decades ago.

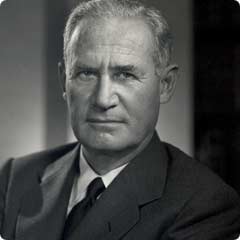

Paying tribute to the publishers who made the Times what it is today, Schwartz mentions Adolph Ochs (1896-1935), who modernized it; his son-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger (1936-1961), who kept it going as a paper of record (“All the news that fit to print”), and his son Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger (1963-1992).

Ochs, a German Jew from Tennessee, was an assimilationist who looked down on new Jewish immigrants who spoke Yiddish. Arthur Hays Sulzberger was an arch assimilationist who advised President Franklin Roosevelt not to appoint Felix Frankfurther to the U.S. Supreme Court out of fear that his appointment would galvanize antisemites. And like his father-in-law, he opposed Zionism.

Bending over backwards to prove it was not a “Jewish” newspaper, the Times purged Jewish-sounding bylines, usually forcing reporters whose first name was Abe or Abraham to sign their names with initials — A.M. Rosenthal, A.H. Raskin and A.H. Weiler.

As a result of its aversion to being identified as a partisan Jewish paper, the Times failed miserably in its reportage of the Holocaust, Schwartz writes. “The Times‘ failure to report on the obliteration of the Jewish presence in Europe gave cover in the media to those whose concern for Jews was limited or who felt that if the Times didn’t focus on Jews, maybe the story was not at all it was rumoured to be.”

In Schwartz’s estimation, its lackadaisical coverage of the Holocaust was its “greatest failure.” As he notes, only six times in six years did the Times‘ front page mention Jews as the Nazis’ chief victim.

More egregiously, the Times downplayed stories of Nazi massacres of Jews. On July 12, 1944, for example, a news story that 400,000 Hungarian Jews had been deported to their deaths and that an additional 350,000 Jews were to be murdered shortly was placed on page 12.

As for Zionism and Israel, the Times supported the 1947 United Nations plan to partition Palestine, but only as a way of bolstering the prestige of the UN. And the Times, he adds, did not endorse Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948.

A few months later, Sulzberger wrote to a fellow anti-Zionist, “I feel no closer to Israel than I do to Britain and China.”

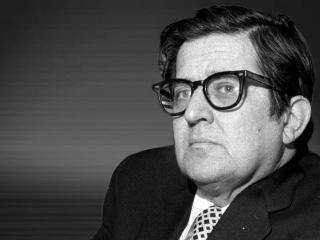

In Schwartz’s judgment, Abraham Rosenthal, the Times‘ first Jewish executive editor, was a seminal figure in its evolution as a national newspaper. A former foreign correspondent based in India and Poland, he brightened up the paper, expanded news coverage, introduced new technology and launched new and exciting stand-alone sections.

One of his successors, Howell Raines, won plaudits for coverage of the terrorist events of Sept. 11, 2001, but jeopardized his legacy with the Jayson Blair plagiarization affair and Judith Miller’s misrepresentation of weapons of mass destruction in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq.

Bill Keller, who succeeded Raines, “rescued” the Times and sought a 21st century audience in the digital world. Jill Abramson, Keller’s successor and the Times‘ first female executive editor, brought women into leadership positions. Abramson, whom Schwartz describes as “tough-minded, impatient, humorless and abrasive,” was sacked this past May.

Interestingly, the current publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., explained she had been fired because she had engaged in “arbitrary decision-making, a failure to consult and bring colleagues with her, inadequate communication and the public mistreatment of colleagues.”

Abramson’s successor, Dean Baquet, the first African American executive editor, faces the kind of problems that have toppled a succession of dailies of late. But in Schwartz’s opinion, the Times, though diminished in terms of its power, will continue to exert influence in American journalism.

Schwartz is confident that the print edition will survive in “some form for the foreseeble future.” But he predicts that the digital edition will gradually take its place in a revolutionary transition.