Israel was once inextricably associated with the kibbutz, a collective farming commune based on egalitarian values and dedicated to the proposition that Israel should be a Jewish socialist state. For decades, this model worked harmoniously, but in the last few decades it has gradually broken down, radically changing the complexion of the kibbutz.

Toby Perl Freilich’s fascinating documentary, Inventing our Life: The Kibbutz Experiment, charts the incremental transformation of the kibbutz. The film is now available on the ChaiFlicks streaming platform.

I was drawn to it due to my personal connection to the kibbutz. Less than a month after the 1967 Six Day War, I visited Israel for the first time. Shortly after my arrival, I started working as volunteer on Ma’agan, a kibbutz on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. I spent the sweltering summer months there.

My routine was etched in stone.

I rose before dawn, washed, got dressed, and headed in the darkness to the communal dining hall. After a quick breakfast, a jam sandwich washed down by a cup of hot tea, I was ready to pick grapes alongside my fellow volunteers from various countries. We were driven to the vineyards in a wagon drawn by a tractor spewing pungent diesel fuel.

In 1971, I returned to Israel. Thinking I might remain there, I studied Hebrew at an ulpan on Haogen, a kibbutz facing the West Bank and near the seaside city of Netanya. On most mornings, I earned my keep by picking melons.

I also briefly lived on Ma’abarot, a kibbutz across the road from Haogen. There I picked oranges in a dense and aromatic orchard, where breakfast was served early in the morning.

These nostalgic memories were triggered by Freilich’s film, which explores the formation and development of the kibbutz movement.

The young Russian-born men and women who founded the kibbutzim were animated by a revolutionary spirit of creating a new way of life far removed from the shackles of the European shtetl. “We invented our life,” says an old woman who was among the founders of Kibbutz Baram.

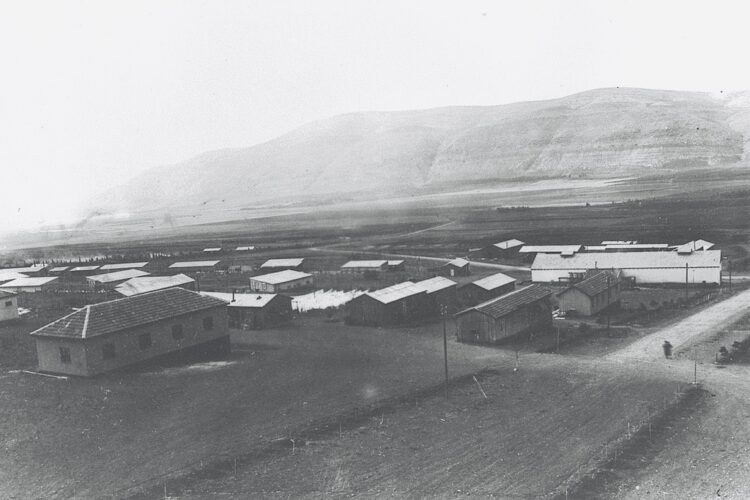

Degania, the first kibbutz, was established in 1910 by a small group of idealists who battled harsh conditions in Ottoman Palestine. Life was so hard back then that the majority of newcomers went back home. The few hardy ones who stayed created a unique and utopian collective lifestyle marked by gender equality, hard work, productivity and modesty.

The kibbutz was the kind of a place which did not require its members to carry a house key or a wallet, says Noga Aulagon, a kibbutznik who earns a living as an architect.

The pioneers who built the kibbutzim broke with bourgeois notions. Children lived apart from parents in special dormitories supervised by nannies. They enjoyed happy, care-free, outdoor lives, but nonconformists tended to be miserable, says an ex-kibbutznik.

Schools sought to produce a “new Jew” — proud fighters who could defend the land.

Kibbutzim were instrumental in expanding the boundaries of the Yishuv — the Jewish community in Palestine — laying down its infrastructure, and building a military force to defend Jews from Palestinian Arab attacks.

Kibbutzniks filled the ranks of the officer corps in Israel’s armed forces on a disproportionate basis from the 1948 War of Independence until the Six Day War.

In some instances, the kibbutz attracted settlers from the Diaspora. Jews from the United States formed Sasa in 1949 on the ruins of an abandoned Arab village near the Lebanese border. At the beginning, they had no electricity or fresh water, but they persevered. “We were fired up by the idea of a Jewish state,” says one of its original residents, Yona Hirschberg. “We were building a new society.”

During the 1950s and 1960s, kibbutzim flourished, backed financially by the ruling Labor Party government. Kibbutzniks, comprising only five percent of the Jewish population, felt special.

Agriculture was the mainstay of the kibbutz economy, but industry gradually replaced it during the 1970s and beyond.

To the flood of Arab Jewish immigrants who poured into Israel from the late 1940s and early 1950s onward, the kibbutz was an alien institution. Very few of these newcomers were interested in settling on a kibbutz. Conversely, kibbutzim generally were not receptive to them.

The victory of Menachem Begin’s right-wing Likud Party in the 1977 election was a crushing blow to kibbutzim. Begin was antagonistic to the socialist ethos of kibbutzim and disparagingly labelled kibbutzniks as “millionaires with swimming pools.”

By the mid-1980s, indebtedness and runaway inflation played havoc with most kibbutzim. In the face of these upheavals, they introduced privatization modifications that shocked and disappointed old-timers.

Communal dining halls were phased out. The practice of collective child rearing disappeared as children began living with their parents. Members were charged for certain services. And in a seminal development, kibbutzniks were assigned differential salaries.

“We had to recreate the kibbutz to keep it,” explains a consultant hired by a kibbutz. “We had to start living like the rest of the country.”

By 2010, when Inventing our Life: The Kibbutz Experiment was released in theaters, only one-quarter of Israel’s 270 kibbutzim were socialist in terms of their economies. Degania, the oldest one, was not among them.

The kibbutz eventually morphed into “a commune of private families,” as Freilich puts it.

Only the richest kibbutzim, buoyed by profitable factories, could afford to hew to their egalitarian and socialist traditions in a state whose economy was increasingly capitalistic.

In addition, kibbutzim were losing their youngest members. David Ben-Avraham, the first baby born on Ein Shemer, admits that all five of his children left the kibbutz for greener pastures in towns and cities.

In Hulda, every member of the third generation departed.

By Freilich’s estimation, the kibbutz has failed to preserve its founding philosophy and traditions. But even detractors probably agree that its contributions to Israel have been nothing short of amazing.