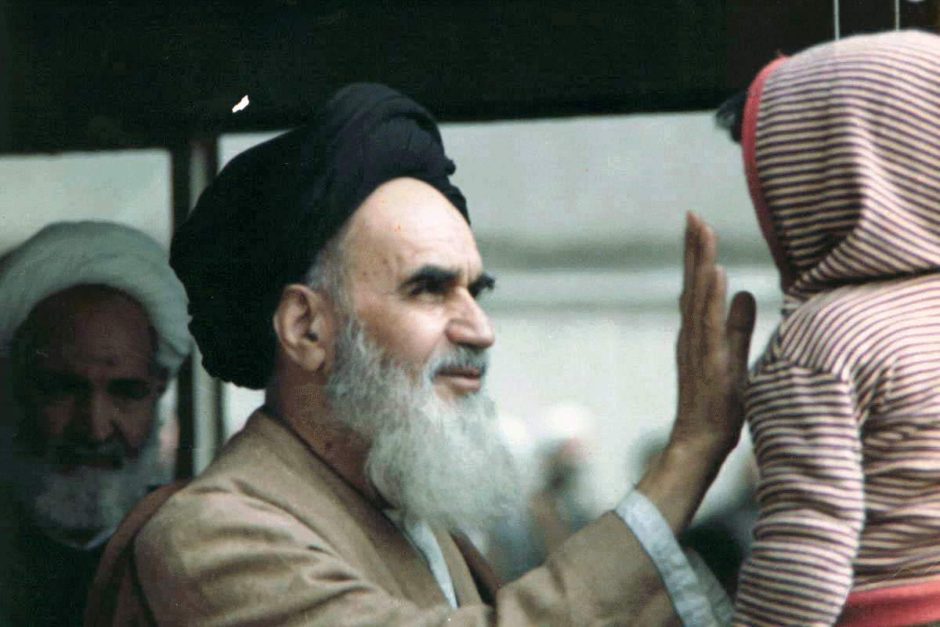

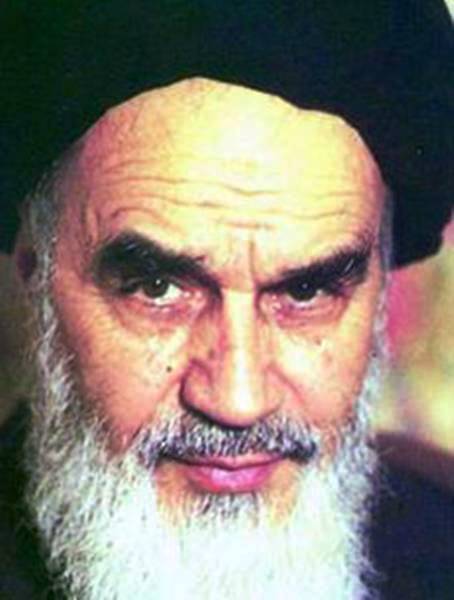

On February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini landed at Tehran’s Mehrabad International Airport after more than 14 years in exile. And the world changed forever.

An Iranian monarchy that had seemed so secure had now crumbled into dust and the country’s ruler, Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, had already fled the country.

A few months later, at a talk I gave in Toronto to the Friends of Pioneering Israel, a now-defunct left-Zionist group, I suggested that this would prove to be an event even more important that the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

I was right. The Soviet Union no longer exists, while Iran’s Islamic Republic goes from strength to strength.

Every few months, however, some newspaper columnist assures readers that the regime is in danger and on the verge of collapse. This usually happens when there has been some economic setback in Iran.

Two recent examples picked at random are a November 23 Washington Post piece by Anne Applebaum entitled “Iran’s Regime Could Fall Apart. What Happens Then?” and a January 1 commentary in the New York Post by Alireza Nader, “Iranian Mullahs’ Lock on Power is Now Shakier than Ever.”

I have never been one of these journalists, having written numerous opinion pieces, dating back to the mid-1980s, cautioning against such wishful thinking. Just last week, I told students in one of my classes that Iran remains a very strong state, supported by a robust form of religiously-based nationalism.

It exports its ideology throughout the Middle East and farther afield. It provides weapons to proxies and supports terrorism, while also working diligently to destroy Israel.

How did all this come about? It certainly surprised many in the West. I was on an airplane from London to Montreal in late 1978, and a Canadian diplomat assured me that the Shah’s regime would survive.

It all began in 1963, when the Shah instituted a series of measures intended to accelerate Iran’s modernization. The other implicit purpose was to strengthen and centralize his power. These reforms were known as the White Revolution.

A high-handed autocrat, he had already displeased many Iranians by acceding to the overthrow of a popular nationalist prime minister, Mohammad Mosaddegh, 10 years earlier, in a coup d’état engineered by the United States and Britain.

But opponents and dissidents found themselves at the mercy of his dreaded secret police, the SAVAK.

The powerful Shi’a clergy was enraged both by its reduced power and authority, and by the increased penetration of Western culture. One of the strongest voices against these reforms came from a cleric named Khomeini.

On January 22, 1963, he issued a strongly worded declaration denouncing the Shah and his plans. In return, he was arrested and then exiled to Turkey.

He then settled in the Shi’a holy city of Najaf in Iraq, where he continued to call for the Shah’s overthrow and the establishment of an Islamic republic in Iran. Forced to leave Iraq on October 6, 1978, Khomeini moved to a suburb of Paris — but, as we know, not for long.

Following his return to Iran, Khomeini oversaw the writing of the country’s new constitution, which was passed in a referendum held on December 2-3, 1979.

The constitution has been called a hybrid of theocratic and democratic elements. While there are elections for the presidency and the Majlis, or parliament, they are subordinate to the Council of Guardians, a clerical body, and the Supreme Leader.

As the highest-ranking political and religious authority in the nation, the ayatollah became the country’s ruler, and governed until his death on June 3, 1989. His successor, Ali Khamenei, still rules the country.

It hasn’t always been smooth sailing for the regime. The mullahs had to cope with the brutal invasion unleashed by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in 1980. The subsequent eight-year conflict resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Iranians and Iraqis.

The new Iranian leadership also faced resistance from its own people at times. For example, there were major disturbances in 2009 following the clearly rigged re-election of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. The regime responded with violence, and many hundreds of protestors died or were imprisoned in the post-election unrest.

A year ago, Iranians poured into the streets to denounce Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and called for an end to his brutal regime. The sources of popular anger varied, from water shortages to economic collapse to frustration with social restrictions. But the clerical establishment has always weathered these storms.

Ahmadinejad was notorious as a Holocaust denier and also for his statements, made at various times, about the need to wipe Israel off the map. But he only expressed what less outspoken Iranian leaders think. Destroying the Jewish state remains high on their agenda.

In the meantime, Tehran has taken advantage of the chaos unleashed by the Arab Spring, which began in late 2010, by militarily and politically expanding its reach across the Middle East.

Iran now virtually controls the fates of Lebanon, Iraq, and Syria, and supports a Shi’a uprising in Yemen. The Sunni Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia, now live in fear of Iran, so much so that they are even prepared to work clandestinely with Israel. Iran has even had covert contacts with the Taliban in Afghanistan.

Iran poses an existential threat to Israel, while its Syrian government and Hezbollah allies sit on Israel’s northern borders.

The United States for the past four decades has used both the carrot and the stick approach when dealing with Tehran.

President Barack Obama tried to reason with the regime’s political leaders. This culminated in the 2015 nuclear agreement (the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action), signed by Washington along with China, France, Germany, Russia, Britain, and the European Union.

It came after years of tension over Iran’s alleged efforts to develop a nuclear weapon. Iran insisted that its nuclear program was entirely peaceful, but the international community did not believe that. Under the accord, Iran agreed to curb its sensitive nuclear activities and allow in international inspectors in return for the lifting of crippling economic sanctions that had been imposed on Tehran.

On May 8, 2018, President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew from the deal and re-imposed sanctions. He has been far more outspoken than Obama about the dangers posed by the regime.

Tehran was probably continuing its work on developing nuclear weapons in any case. Some experts think that a sufficient number of advanced centrifuges could drop Iran’s breakout time to a nuclear weapon from a year to a few months to even weeks.

Should Iran obtain an atomic arsenal, Tel Aviv may well disappear from the face of the earth. The fanaticism of the Iranian mullahs should never be underestimated.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.