Sizing up the Iran nuclear agreement on its first anniversary on July 14, U.S. President Barack Obama said it had “succeeded in rolling back Iran’s nuclear program (and) avoiding further conflict.”

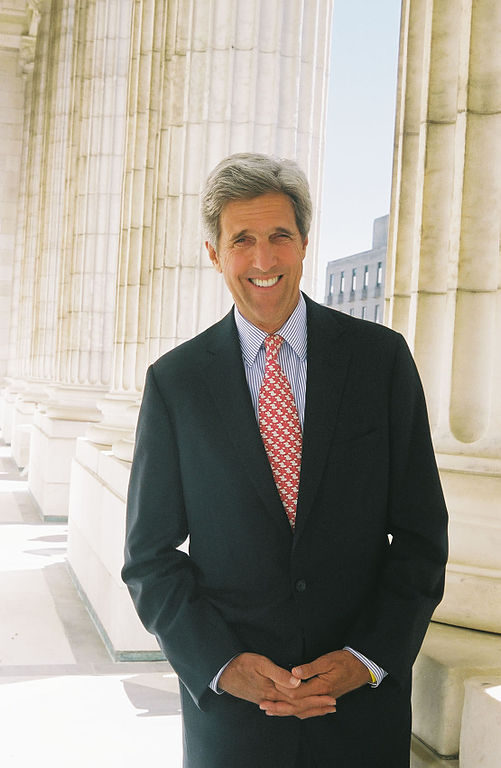

Sticking to the same theme, U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said the landmark accord, signed by Iran and six major powers in Vienna, has accomplished its primary objective — preventing a Mideast war triggered by Iran’s advances in building a nuclear arsenal.

They’re right.

If Iran and its interlocutors — the United States, Britain, France, Russia, China and Germany — had not signed a deal, the consequences might have been catastrophic.

Iran — Israel’s bitter foe since the 1979 Islamic revolution — would probably have stepped up its efforts to develop a nuclear device, a prospect that would have emboldened Israel to seriously consider a risky military operation to destroy or disable Iran’s nuclear sites.

In the past, Israel has threatened to strike Iran. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who branded the agreement as a historic mistake, reportedly came perilously close to ordering air strikes against Iranian nuclear facilities in 2012.

If Israel had gone ahead with bombing raids, which might have set back Iran’s nuclear ambitions by no more two or three years, Iran would have retaliated, launching thousands of long-range missiles at Israeli cities. These strikes would have doubtless killed hundreds, if not thousands, of Israelis and caused immense property damage.

Tit-for-tat exchanges would have embroiled Israel and Iran in what could have been a lengthy war. In all probability, the United States, Israel’s chief ally, would have been sucked into the conflagration. Arab states like Saudi Arabia and Jordan may have been pulled in, too, destabilizing the Middle East.

In short, it would have been a disastrous turn of events, a watershed in the annals of the region.

Fortunately, this cataclysmal scenario did not materialize, leaving Israel safer than it had been before July 14, 2015.

No less a person than the chief of staff of the Israeli armed forces, General Gadi Eisenkot, agrees with this appraisal. As he said a few days ago in Tel Aviv, “This deal has actually removed the most serious danger to Israel’s existence for the foreseeable future and greatly reduced the threat over the longer term.”

In other words, the agreement has bought time, which is no small achievement.

Two years in the making, it’s hardly perfect. Ideally, Iran should have been required to dismantle its nuclear program altogether, as Netanyahu had demanded. But since this was realistically a non-starter, given Iran’s vehement rejection of the idea, the major powers had to settle for less.

Call it a grand compromise, an exercise in real world diplomacy.

Far better than war.

The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, as it’s officially called, freezes Iran’s nuclear program for at least the next decade and subjects it to a rigorous regimen of inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency.

The sanctions that had crippled Iran’s oil-based economy are to be lifted. In return, Iran has agreed to restrict its uranium enrichment program and curb weapons-grade plutonium production. In the last year, Iran has shipped virtually all its enriched uranium to Russia, disassembled two-thirds of its centrifuges, filled a plutonium reactor with concrete and agreed to operate an underground enrichment plant near Fordo under strict limits.

“As a result, all of Iran’s pathways to a nuclear weapon remain closed, and Iran’s breakout time has been extended from two to three months to about a year,” said Obama in his appraisal of the complex agreement, which lead U.S. negotiator Wendy Sherman has likened to a Rubik’s Cube.

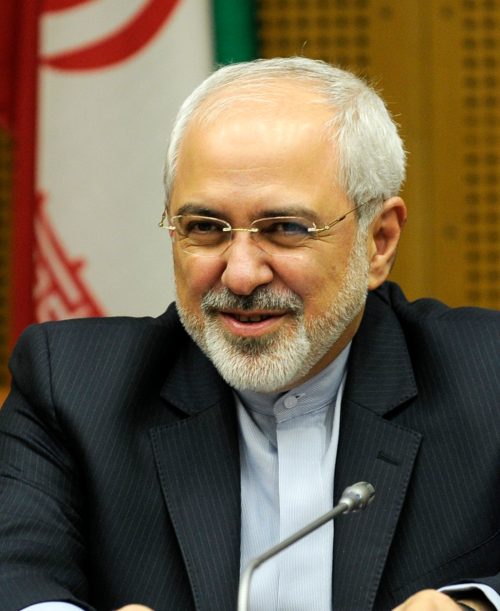

The International Atomic Energy Agency certified in mid-January that Iran is complying with the terms of the agreement. But much to Iran’s annoyance, sanctions relief is unfolding far too slowly, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif told Kerry last week.

According to reports, foreign investors have not returned to Iran in sufficient numbers, while international banks have been slow to resume normal activities, due to the perception they will be subject to U.S. fines or prosecution.

Obama claims that the United States and its partners have upheld their part of the bargain. But Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, who had touted the potential benefits of the agreement, has warned that Iran could restart its nuclear program if it’s not fully implemented.

Even as he lauded the agreement, Kerry acknowledged that the United States has deep differences with Iran.

Iran is still one of the primary supporters of Hezbollah and Hamas, both of which are committed to Israel’s destruction. And Iran is heavily invested in shoring up the regime of President Bashar al-Assad of Syria, which is mired in a civil war.

Due to its close ties with Hezbollah and Hamas, the United States has listed Iran as a sponsor of terrorism. “Iran remained the foremost state sponsor of terrorism in 2015, providing a range of support, including financial, training and equipment, to groups around the world,” the U.S. State Department concluded in a report issued in June.

Iranian leaders regularly call for Israel’s annihilation.

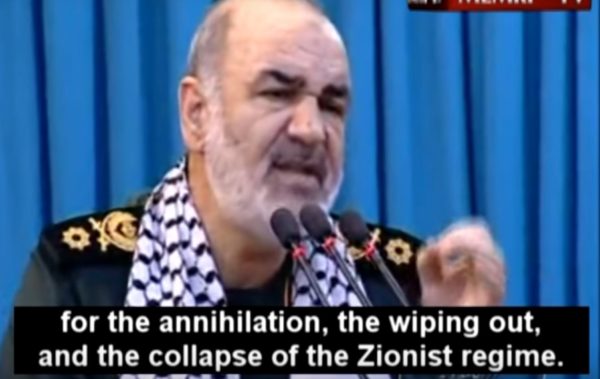

In May, Ahmad Karimpour, a senior advisor to the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ Al Quds Force, boasted that Iran could “raze the Zionist regime in less than eight minutes.” Earlier this month, General Hossein Salami, the Guards’ deputy commander, declared that Iran has assembled more than 100,000 missiles in Lebanon to destroy Israel. Salami said he is waiting for a command to wipe “the accursed black dot” off the map.

Iranian ballistic missile launches are also a source of concern.

In March, two missiles Iran planned to test were emblazoned with the words “Israel must be wiped off the earth.” Although the United States and its European allies have described these tests as “destabilizing and provocative,” they do not run afoul of the nuclear agreement. However, United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki-moon has said the tests “are not consistent with the constructive spirit” of the nuclear pact.

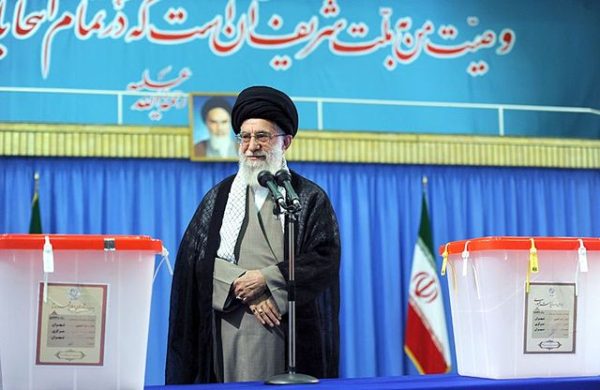

Lashing out, Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has declared that Iran is free to test its missiles.

Significantly, he has ruled out the possibility of future cooperation with the United States beyond the parameters of the nuclear accord. Khamenei, who most recently called Israel “the damned and cancerous Zionist regime,” has taken the United States to task for its “meddling approach and tone” and questioned the deployment of the U.S. Navy’s Fifth Fleet in the Persian Gulf.

Iran is also upset by an April 20 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that nearly $2 billion in frozen Iranian funds can be used to compensate American victims of overseas terrorist attacks attributed to Iranian operatives.

“The Islamic Republic of Iran holds the United States government responsible for this outrageous robbery, disguised under a court order,” Zarif fumed in a letter to the United Nations’ secretary general. “It is in fact the United States that must pay long overdue reparations to the Iranian people for its persistent hostile policies,” added Zarif in a reference to the CIA-supported overthrow of the Iranian government in 1953.

Despite these bitter disagreements, the United States and Iran remain committed to the nuclear accord. But its longevity may be in doubt should Donald Trump defeat Hillary Clinton in the U.S. presidential election in November. Trump has suggested he will renegotiate or renounce the agreement, a development that would cast a giant shadow over the Middle East.