Shortly before Ban Ki-moon stepped down as secretary-general of the United Nations recently, he received a remarkably blunt and bitter letter from the UN ambassadors of eleven Arab countries.

The envoys — representing the predominantly Sunni Muslim nations of Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Yemen, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Oman, Sudan and the United Arab Emirates — levelled a series of accusations against Iran, the preeminent Shiite power in the region.

Accusing Iran of sowing strife and sponsoring terrorism in the Middle East, the ambassadors also criticized Tehran for its “expansionist policies.”

Their indictment was further evidence of the growing rift between conservative Arab countries and Iran and of the religious schism between the Sunni and Shiite branches of Islam.

The Arabs and Iranians have been adversaries for centuries, since the heyday of the Persian empire. During the latter half of the 20th century, the rivalry intensified following Iran’s seizure of the Greater Tunb and Lesser Tunb islands in 1971. These Persian/Arabian Gulf islands, once under British rule, are still claimed by the United Arab Emirates, a member of the informal Arab coalition arrayed against Iran.

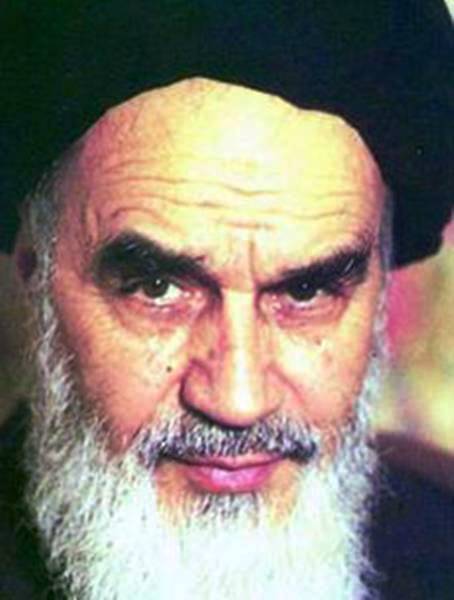

Since the 1979 Islamic revolution in Iran, tensions have escalated. Ayatollah Khomenei, the leader of Iran’s Islamic revolution and its first supreme leader, upset Arab kings by declaring that “the concept of monarchy totally contradicts Islam.”

The Egyptian government soured on Iran after its denunciation of Egypt’s peace treaty with Israel.

Iran, in turn, was incensed by the decision of Arab League countries to support Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War from 1980 onward.

Saudi Arabia and Iran jockeyed for influence in Lebanon, with the latter lining up behind Hezbollah and the former backing the Sunni Sunni Establishment.

More recently, Saudi Arabia severed diplomatic relations with Iran after the Saudis executed a prominent Shiite cleric and Iranian mobs set fire to the Saudi embassy in Tehran.

Today, the Arab camp and Iran are embroiled over the civil wars in Syria and Yemen.

Iran, which formed an alliance with Syria during its war with Iraq, backs the Syrian Baathist regime of President Bashar al-Assad. Pro-American Arab states like Saudi Arabia and Jordan, in alignment with Turkey, have lined up behind rebel units trying to unseat Assad, who inherited his position following the death of his father.

Iran’s efforts to prop up Assad’s unpopular government are supported by Hezbollah, the Lebanese Shiite movement; Shiite militias from Iraq and Afghanistan, and Russia, Syria’s oldest superpower ally.

Yemen is another front where Iran and mainstream Arab nations have clashed.

The conflict in Yemen, one of the poorest nations in the Arab world, broke out in 2015 when the Houthis, a disaffected Shiite minority, ousted the Sunni government of President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi and subsequently seized the capital, Sanaa.

Iran and Yemen’s former president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, support the Houthis, while Arab governments generally back Hadi, who was forced into exile in Aden. (Another combatant, Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, has wrested control of parts of Yemen).

The Saudis, backed by the United States, have deployed air power extensively to pummel the Houthis, but to no avail. The conflict is at an impasse, with civilians having borne the brunt of the suffering. By most accounts, upwards of 10,000 Yemenis have been killed in Saudi bombardments.

Although Arab governments formally endorsed Iran’s nuclear agreement with the six major powers in 2015, they are extremely wary of it. In common with Israel, the Arabs assume that Iran still has nuclear ambitions. They have threatened to build their own nuclear programs should Iran join the nuclear club.

Being wary of Iran’s behavior and intentions, 11 Arab states took the extraordinary step of airing their grievances and suspicions publicly. The letter their UN ambassadors sent to Ban Ki-moon is astonishingly bold in tone and substance.

They wrote: “The nuclear agreement gave the Islamic Republic of Iran the opportunity, after years of sanctions, to create normal relations with its neighbours and demonstrate a new commitment to regional stability and respect for the sovereignty of other nations. Unfortunately, since the signing of the nuclear deal, we have seen nothing but increased Iranian aggression in the region and the continuation of support for terrorist groups.”

And in an allusion to the dispute over the Greater and Lesser Tunb islands, they added: “We reaffirm that the stability and economic prosperity in the Arabian Gulf region is founded on the importance of maintaining good-neighbourliness and the principles of sovereignty, independence and non-interference in domestic affairs, in stark contrast with the Islamic Republic of Iran’s radical approach that undermines security and stability in our region …”

Israel would concur with this appraisal of Iranian policy. Iran, being committed to Israel’s destruction, uses proxies like Hezbollah and Hamas to attack Israel.

The semi-official Fars news agency recently quoted one of Iran’s top general, Mohammed Hossein Bagheri, as acknowledging that Iran built a factory in Aleppo, Syria, for the express purpose of manufacturing missiles for Hezbollah. These missiles were deployed by Hezbollah during the 2006 Second Lebanon War.

Israel believes that most or all of the 100,000 missiles Hezbollah possesses today were supplied by Iran.

Iran’s rejectionist stance toward Israel was starkly illustrated last month in Tehran. The Iranian foreign minister, Mohammed Javad Zarif, and the Speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani, cancelled meetings with German Vice-Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel after he demanded Iran’s recognition of Israel as a precondition for a resumption of full diplomatic ties between Iran and Germany.

Predictably, an Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesman dismissed Gabriel’s demand as completely unacceptable.

Iran marches to its own music, alienating the Arab bloc and alarming Israel.