Iran’s film industry is subjected to censorship and hobbled by a poor global distribution system, but it has chalked up stellar achievements nonetheless.

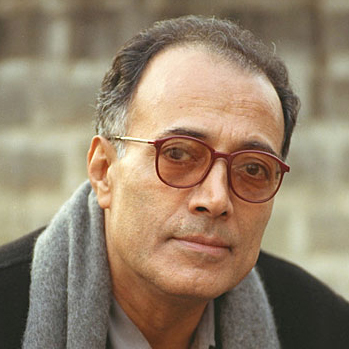

It has produced internationally-recognized directors like Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf and films like A Separation (the first Iranian movie to win the best foreign language film award at the Academy Awards) and Hamoun, which critics in 1998 called the finest Iranian movie ever made.

In recognition of its important place in Iran’s culture, the TIFF Cinematheque is presenting 15 Iranian feature films and three shorts.

I for Iran: A History of Iranian Cinema by its Creators runs from March 5 to April 4. Films made before and after the 1979 Islamic revolution will be presented.

A preview:

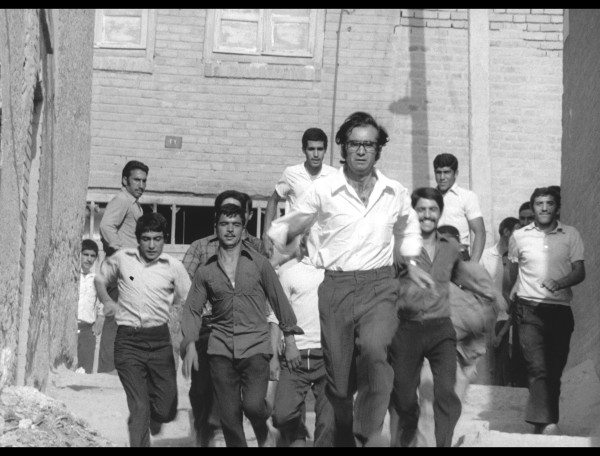

Hamoun, directed by Dariush Mehrjui and released in 1990, offers a glimpse of middle-class life in contemporary Iran. Hamoun, a medical equipment salesman by vocation and a PhD student by avocation, is embroiled in divorce proceedings.

His wife, Mahshid, a painter, can no longer bear him and wants to end their marriage. Once drawn to his eccentricity and his joie de vivre, she is now fed up with his dark pessimism and tyrannical tendencies. “My life with him is wasted and has no meaning,” she says.

He, in turn, is weary of her profligate spending habits and the strong odours of paint and turpentine emanating from her studio. Worse still, he doesn’t appreciate her paintings any more. However, he still loves her and resists his lawyer’s increasingly insistent advice to grant her a divorce.

Their respective grievances are certainly serious, but what ultimately draws them apart are inherent class differences. She’s a spoiled and pampered product of the upper middle-class. He’s from a humbler background.

Flitting from the present to the past and back again, and brightened up by forays into the surreal, Hamoun is a spare and subtle examination of a relationship gone sour. The cast is excellent.

***

Still Life, directed by Sonrab Shahid Saless, is a somber portrait of a railway worker nearing the end of his career in the backwoods of Iran.

Mohammed, simple and illiterate, performs one task several times a day. As a train approaches, he lifts a safety gate, standing erect as the carriages clack and clatter by him. Once the train has passed, he lowers the gate and returns to the hut, where he sits until the next scheduled train is due. It’s a highly regimented existence, but he’s been at it for 33 years.

A taciturn man, he and his passive and obedient wife share a cottage by the tracks. As he goes about his business, she quietly weaves a carpet on a loom. Occasionally, at his curt command, she brings him tea, and he sips it from a small saucer in Iranian fashion. They eat their meals on the floor, the food laid out on a tablecloth.

Invariably, they exchange few words. Once in a while, he pensively smokes a cigarette, coughing as he does so. As darkness falls, she beds down for the night on the floor and he turns off the light, fumbling in the dark. Judging by their unchanging routine, their life together seems stable, arid and dull.

When their son, a soldier, comes home for a short break, he barely communicates with his parents. “Give me some tea,” he barks before he lies down on a cot to catch up on some sleep.

When two officials from the railway company pay him a surprise visit, he asks for his new year bonus. It’s coming, they reply.

When he receives a letter from the company, he asks the postal carrier to read it. The news is bad. Mohammed’s services are no longer required. This means they will be homeless soon. “Go and complain,” his wife urges. Before he can do so, his replacement, a much younger man, arrives at his doorstep.

In despair, he tells his wife, “I’ve been dismissed,” a phrase he mutters several more times in indignation and resignation. Hitching a ride to the nearby town, he pleads for his job.

Still Life, an austere film which came out in 1974, envelopes a viewer with its deceptive power. The actors deliver strong performances.