Israel and its northern neighbor, Lebanon, are embroiled in three disputes that could spill over into violence. On February 12, Lebanese President Michel Aoun warned they could yet trigger a war.

Despite the gravity of the situation, major newspapers in North America have virtually ignored the brewing tensions, possibly because they were overshadowed by a sudden outbreak of fighting on February 10. During that day, Israel shot down an Iranian drone over Syria, a Syrian missile downed an Israeli F-16 jet returning to its base in Israel, and Israeli aircraft bombed Syrian anti-aircraft batteries and Iranian bases in Syria.

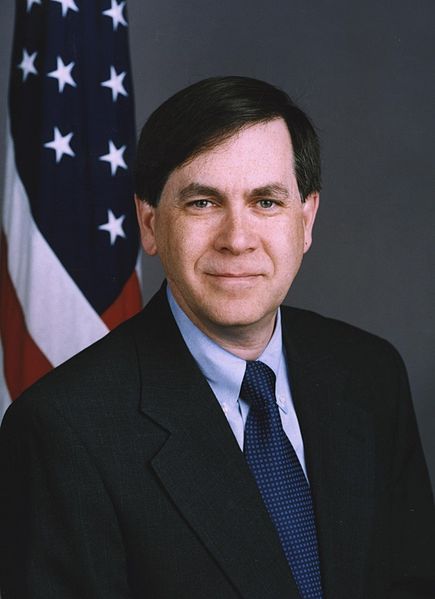

The United States, however, has paid close attention to these simmering conflicts. The acting Assistant U.S. Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, David Satterfield, has tried in vain to defuse them. He is scheduled to resume his shuttle diplomacy in March.

His boss, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, visited Lebanon in the first week of this month to discuss the points of contention. He conferred with Aoun, Prime Minister Saad Hariri and Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri.

The issues causing so much acrimony turn on the construction of an Israeli security wall along the Lebanese border, a disagreement over rights to natural gas and oil exploration in the Mediterranean Sea, and an Israeli claim that Iran is constructing missile factories on Lebanese soil.

Israel is in the midst of replacing a border fence with a wall. Consisting of berms, concrete obstacles and physical barriers, it runs along the route of the Blue Line, which was established by the United Nations following Israel’s unilateral withdrawal from southern Lebanon in May 2000.

Lebanon’s position is that the land frontier should be based on the 1923 demarcation line between Lebanon and Palestine. In essence, the dispute is about 860 square meters (9,256 square feet) of territory at 13 contested points. It’s not clear whether Har Dov, or Shaaba Farms, which Israel captured from Syria during the Six Day War, is part of the dispute.

The United States believes that Israel should not have begun work on the barrier until both countries had reached an agreement on the exact contours of the border.

When Satterfield launched his mission, he proposed that Lebanon should accept the so-called “Hof line,” which his predecessor, Frederic Hof, devised in April 2012. This gave Lebanon 60 percent of the disputed 860 square meters. When the Lebanese balked, Satterfield offered Lebanon 75 percent. Israel disagreed, and the impasse deepened.

Of late, the Lebanese government has suggested that the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL) — which was set up in 1978 after Israel’s first invasion of Lebanon — should demarcate the border. This would requires a United Nations Security Council decision to expand UNIFIL’s mandate.

Israel maintains it is building the wall on its sovereign territory in accordance with a United Nations Security Council resolution passed in 2000. Israel says it is not interested in picking a fight with Lebanon over this issue.

Aoun, a Christian aligned with Hezbollah, a pro-Iranian force which fought a war with Israel in 2006, has warned that Israel has no right to build it until an agreement is in place. Once this happens, he said, Israel would be free to “build any wall (it) wants on (its) land.”

Hezbollah has threatened to open fire on Israeli workers building the wall, but Israel intends to proceed with the project. Israel has warned Hezbollah it will “pay dearly” if it inflames tensions.

In the meantime, Israel is preparing for the worst.

Last week, in the wake of a report that the Iraqi Shi’a militia Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba would support Hezbollah in the event of armed hostilities with Israel, the Israeli army conducted military exercises to prepare for a possible war in Lebanon.

Israel’s maritime dispute with Lebanon, which dates back to 2010, is also serious.

On February 10, as Israel, Iran and Syria tangled, Lebanon signed its first contract with a consortium of French, Italian and Russian companies to drill for gas in waters of the Mediterranean coveted by both Israel and Lebanon.

Israeli Defence Minister Avigdor Liberman described the deal as “provocative.”

Lebanon says that exploratory offshore drilling will begin next year in a field known as Block 9. There are about 865 million barrels of oil and 96 trillion cubic feet of gas in the triangular 854 square kilometre area, all of which Israel claims for itself.

Lebanese Foreign Minister Gebran Bassil has sent a letter to the United Nations affirming Lebanon’s right to defend itself and its economic interests. Hezbollah has said it will “decisively confront any assault on our oil and gas rights.” In plain words, Hezbollah is ready to fire on Israeli oil and gas rigs in the Mediterranean.

According to Tillerson, Hariri is open to a solution “that will be fair to everyone.” But when the commander of the Lebanese armed forces, General Joseph Aoun, was asked what his troops should do if Israel violated Lebanese territorial waters, Hariri reportedly said, “You shoot at them.”

Washington’s objectives, as asserted by Tillerson, are to ensure the unimpeded flow of oil and gas from the Mediterranean, to shield American oil and gas companies in Israel and Cyprus from potential conflicts, and to prevent Hezbollah from becoming too enmeshed in Lebanon’s maritime dispute with Israel.

The third aspect of Israel’s conflict with Lebanon turns on the allegation that Iran is setting up arms factories capable of manufacturing heavy weapons, which would most likely end up in the hands of Hezbollah.

On January 28, Israel’s chief military spokesman, General Ronen Manelis, charged in an Arabic op-ed piece in the Lebanese media that Iran is converting Lebanon into “one big missile factory,” and that Lebanon itself has become a “branch” of the Iranian Islamic Republic.

Liberman was even more emphatic. On January 31, he said, “Lebanon’s army and Hezbollah are the same — they will pay the full price in the event of an escalation.” In other words, Lebanon will be held to account should Israel and Hezbollah find themselves at war.

Interestingly enough, Bahrain — an ally of Saudi Arabia — is on the same page as Manelis and Liberman with respect to Hezbollah. Speaking in Cairo recently, Bahrain Foreign Minister Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmed al-Khalifa charged that Hezbollah has taken “total control” of Lebanon. As he put it, “Iran’s biggest arm in the region at the moment is the terrorist Hezbollah arm.”