Syria, Israel’s northern neighbor, has been antagonistic toward Israel since its birth as a nation in 1948. It would be fair to say that Syria, often called the beating heart of Arab nationalism, has been one of Israel’s fiercest, most indomitable enemies.

All this could change in the future if Israel plays its cards right and reaches an historic accommodation with the new Syrian government headed by President Ahmed al-Shara.

There are signs that Israel is embarking on this road. If this proves to be the case, Israel and Syria could well sign a historic peace treaty, with all its attendant consequences.

In the meantime, the Syrian government can take a few meaningful steps to bring this objective closer.

It can eliminate Iran’s influence in Syria and leave its anti-Israel Axis of Resistance. It can remove Palestinian and Hezbollah forces on its territory. It can improve its heretofore poor relationship with the United States, which has accused Syria of being a state sponsor of terrorism.

U.S. President Donald Trump got the ball rolling earlier this month by lifting economic sanctions on Syria and urging Shara to join the 2020 Abraham Accords and thereby normalize Syria’s relations with Israel. Trump said that, while Shara was open to the idea, there was “a lot of work to do” before this can be achieved.

It goes without saying that the road to normalization will be long and bumpy, since Syria and Syrians regard Israel as a regional rival and foe.

Syria opposed the formation of Israel and went to war with it following its declaration of statehood. Syria signed an armistice agreement with Israel in 1949, but a new source of friction, the demilitarized zones around the Sea of Galilee, triggered armed skirmishes in the 1950s and 1960s.

Syria’s decision to allow the Palestine Liberation Organization to establish bases on its soil from which to launch attacks against Israel further heightened tensions.

Israel and Syria fought during the 1967 Six Day War, resulting in Israel’s conquest of the Golan Heights, from which Syrian gunners had fired on Israeli kibbutzim.

Syria attempted to regain the Golan during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, but Israel defeated the Syrians and their Arab allies in ferocious battles.

Israel and Syria were embroiled in a brief war of attrition in 1974, prompting U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to intervene. He cajoled Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and Syrian President Hafez al-Assad to sign a disengagement agreement, which both sides would honor, bringing a measure of stability to Israel’s northern border.

During Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the Israeli Air Force destroyed Syria’s air defence batteries, and Israeli and Syrian tank forces clashed.

Thanks to U.S. diplomacy, Israel and Syria engaged in direct and indirect peace talks from the 1990s onward, but these efforts bore no fruit.

Syria, a Russian client state, formed an alliance with Iran — Israel’s deadliest enemy — in the early 1980s. Syria also cultivated close ties with Hezbollah, an Iranian proxy hostile to Israel.

From 2013 until last year, Israel periodically bombed Iranian bases in Syria, hit Hezbollah arms convoys en route to Lebanon, and struck Syrian anti-aircraft systems.

Syria’s authoritarian ruler, Bashar al-Assad, who inherited his position from his father in 2000, was deposed last December by Syrian rebels spearheaded by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), an Islamist force led by Shara and headquartered in the northwestern Syrian province of Idlib.

Shara, who had been an Islamic State and Al Qaeda fighter in Iraq, moved to Syria to fight the Assad regime in the civil war, which broke out in 2011. Shara assumed the Syrian presidency shortly after Assad’s fall and flight to Russia.

From the outset, Israeli leaders from Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu on down viewed Shara and his transitional government with a high degree of suspicion.

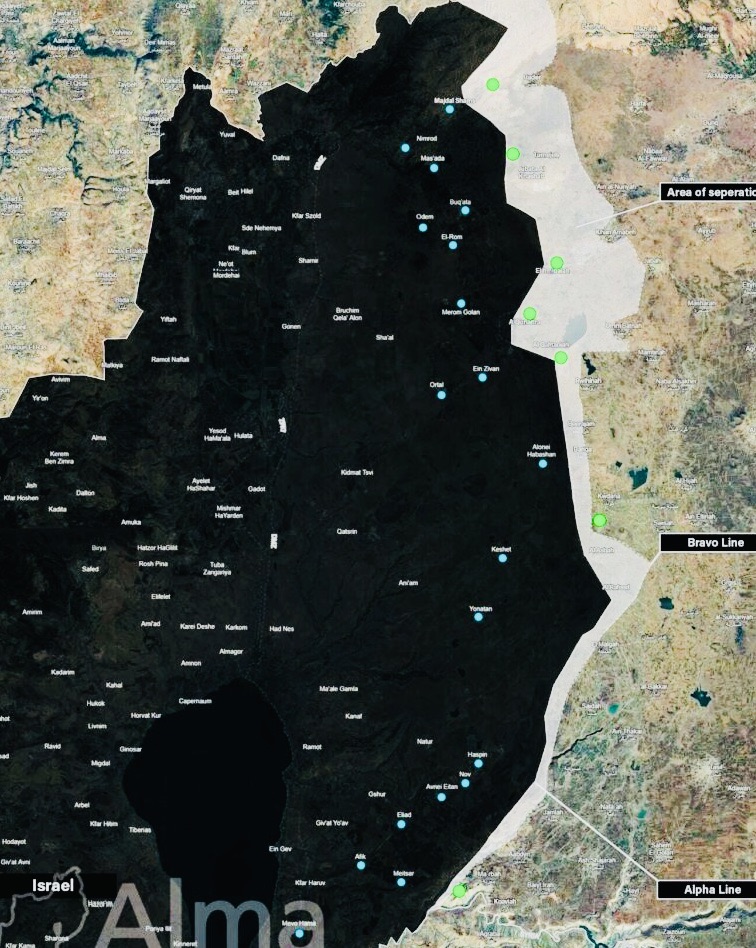

Netanyahu, having been influenced by the trauma of October 7, announced that Israel would establish a buffer zone in southern Syria to ensure the security of Israelis living near the border.

Starting last December, the Israeli army seized a United Nations demilitarized zone inside Syria established in 1974, set up nine military positions there, and took control of the Syrian side of Mount Hermon.

“Israel is in Syria due to October 7,” says Sarit Zehavi, the president of the Alma Research and Education Center, which studies Israeli northern border issues. “Israel understood that we can no longer let radical elements build military capabilities on the other side of our border. We can’t let the monster grow. We have to cut it down while it’s small. That’s the basic idea.”

Hewing to this doctrine, Israel bombed Syrian military sites, destroying airplanes, armor and a wide range of weaponry, so that they would not fall into the hands of anti-Israel forces.

Israel, too, pledged to support the Syrian Kurds and protect the Druze in Syria by military means, if necessary.

Israeli Foreign Minister Gideon Sa’ar justified these moves due to his suspicion of Syria’s post-Assad political order. “The new government in Syria is an Islamic jihadist terrorist group from Idlib that seized Damascus by force,” he said last February. “We are all happy about Assad’s departure, but we must be realistic about Shara.”

Israel Katz, the Israeli defence minister, also used harsh language to describe Shara.

Syria denounced Israel’s maneuvers, but the United States quietly supported Israel. Nader al-Khalil, a Syrian researcher, believes that Israel’s freedom of movement in Syria has been dependent on U.S. backing and hinged on the weakness of the Syrian state in the post-Assad era.

The Israeli government has pursued a confrontational policy in Syria, despite comments by Shara that he seeks no conflicts with Israel.

Israel’s aggressive position has elicited criticism from even its friends.

Shira Efron, the research director of the Israel Policy Forum, co-authored an essay in Foreign Affairs recently in which she suggested that Israel is engaged in “dangerous overreach” in Syria that could create new enemies.

Her co-author, Danny Citronowicz, a fellow at Tel Aviv University’s Institute for National Security Studies, believes that the new Syrian government should be judged on its merits, and that Israel has been presented with a golden opportunity to convert Syria into a peaceful neighbor.

His colleagues, Nir Boms, Carmit Valensi and Mzahem Alsaloum, recently published a probing piece on Israel-Syria relations in which they advise the Israeli government to tread carefully.

“Israel’s approach to Syria since the fall of Assad has been shaped by security concerns …” they write. “(It) has been driven by a desire to prevent another security vacuum while maintaining its freedom of action to neutralize emerging threats.”

Israel’s military operations, aimed at eliminating potential threats, may have instead “fueled growing resistance and increased the likelihood of future clashes — ironically, the very scenario it aimed to prevent by intervening in the first place.”

These operations have begun to erode “the legitimacy of Syria’s new government, which is increasingly seen as incapable of asserting control or exercising sovereignty in the face of Israeli actions,” they add. “Although Israel expresses little trust in the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham-affiliated government due to its Islamist background, this perception of weakness could inadvertently strengthen the extremist elements that Israel seeks to contain. Meanwhile, international criticism of Israel’s actions in Syria is increasing, with Israel being accused of violating Syrian sovereignty without clear justification.”

While Israel’s policy of supporting the Kurds and the Druze may seem like a prudent strategy in the short term, they note, it could prove “counter-productive in the long term” if treated as the primary framework for engagement with Syria.

“By encouraging the de facto fragmentation of Syria into ethnic and sectarian enclaves, Israel risks undermining efforts to stabilize the region. This policy, although seemingly aligned with Israel’s security interests, could inadvertently foster a cycle of sectarianism that would ultimately benefit Israel’s rivals — including Iran.”

Israel’s moves in southern Syria have provided Iran with a “convenient pretext” to call for the revival of its “resistance” against Israel from Syrian territory, they warn.

Iran’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei, has declared that “brave Syrian youth” will expel “Zionists” from Syria. The commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps, Hossein Salami, has stated that the situation in which “Zionists” can “look into the homes of Damascus is intolerable.” Ali Akbar Ahmadian, the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, has said that Israel’s occupation of Syrian lands will foster “resistance.”

Boms, Valensi and Alsaloum point out that Syria’s new rulers have broken with the policies of the past. They have kept their distance of Hamas leaders, expelled the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, arrested two senior members of Islamic Jihad, and countered Hezbollah’s attempts to smuggle weapons across Syria’s border with Lebanon.

Israel’s policy in Syria, they go on to say, “heightens the risk of further deterioration in Israeli–Turkish relations.”

Turkey, an ally of HTS, seeks to establish military bases in Syria, a prospect that concerns Israel. Boms, Valensi and Alsaloum advise Israel to display moderation: “While Turkey’s policies have historically been hostile toward Israel, it plays a different strategic role than Iran. Despite its opposition to Israeli policies in some areas, Turkey is unlikely to become a full-fledged enemy of Israel due to its opportunistic approach, its membership in NATO, its relationship with the United States, and its strategic interests in the region.”

In closing, they argue that Israel’s “continued emphasis on military presence, airstrikes, and protecting minorities in Syria might contribute to fragmenting the country, weakening the central government in Damascus,” and, ironically, furthering Iran’s interests, since Iran benefits from Syria’s “lack of central authority.”

In addition to Iran’s “malign activity,” a fractured Syria would provide “fertile ground for other radical elements to flourish,” such as Islamic State or Al-Qaeda, all of which the new Syrian regime is currently suppressing.

“One could also argue that Israel’s current policy contradicts a core principle shared by both Israel and the United States: the need to strengthen central governments in fragile Arab states so they can better confront non-state actors, which Iran could exploit to expand its influence, primarily in Lebanon (via Hezbollah) and Iraq (via pro-Iranian Shiite militias).”

Consequently, a paradox may be emerging.

“While Israel advocates for bolstering Lebanon’s central government to weaken Hezbollah, and while the United States works to integrate Shiite militias into Iraq’s official security forces to reduce their autonomy and curb Iran’s influence in Syria, it is Israel itself that is actively working to undermine the central authority. While Israel might enjoy greater freedom of action in a fragmented state lacking a strong government, it would also face a proliferation of threats, requiring even greater investment of resources and attention, and could entangle itself in yet another arena.”

In their view, Israel should pursue an alternative path to better serve its long-term interests.

“Rather than focusing on fragmentation, Israel could capitalize on its recent military successes against Iran, Hezbollah, and Hamas and pursue a more constructive strategy. With its military strength recently on display, Israel has an opportunity to shift its approach and engage in a different dialogue with the new Syrian government.

“Although Syria’s future remains uncertain, Israel should take proactive steps to reduce the risk of escalation by pursuing a series of understandings and agreements with the Syrian administration, starting with border security arrangements and potentially expanding to broader areas of cooperation.

“As for Turkey, Damascus, long seen as a key axis of conflict, could become a potential venue for Israeli–Turkish cooperation. Given that both countries face shared security concerns regarding Iran’s influence, if the two countries can overcome their current dispute and establish a joint framework of understanding, it could evolve beyond a simple deconfliction mechanism. For instance, it might include limitations on the deployment of Turkish air defence systems in Syria, which could pose a threat to Israel. This could open the door for dialogue and joint efforts aimed at stabilizing the country and combating radical elements, an interest of both Israel and Syria.”

It would appear that Israel recognizes these realities and has begun to adjust its policy with respect to Syria.

On May 12, at a press conference in Jerusalem, Sa’ar said, “We want good relations with the Syrian government … but we naturally have security concerns.”

On May 16, Channel 12, Israel’s leading television station, reported that Israel and Syria held secret talks in Azerbaijan mediated by the United Arab Emirates. They took place a day after Trump invited Shara to join the Abraham Accords.

Shara confirmed that these talks had taken place.

Wael Alwan, a Syrian researcher, believes that certain issues will need to be discussed before Syria can enter the Abraham Accords. The most notable of these would be Israel’s withdrawal from Syrian territories occupied since last December.

It remains to be seen whether Israel is prepared to do this. Certainly, Israel has no intention of withdrawing from the Golan, which was annexed by Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s government in 1981.

The months ahead will determine whether Israel and Syria can break with the past and usher in a promising and mutually beneficial era of cooperation and, perhaps, even friendship.