Israel and Turkey, two of the most important powers in the Middle East, appear to be moving closer to a rapprochement that could end five years of mutual recrimination, bitterness and estrangement.

But is it another false start?

Nearly two years ago, after Israeli negotiator David Meidan appeared to have reached a breakthough reconciliation agreement with his Turkish counterpart, Hakan Fidan, newspapers reported that Israel and Turkey were on the cusp of resolving their differences.

In the latest chapter of this on-again, off-again diplomatic dance, Israel and Turkey resumed high-level talks in Zurich last month, reaching a preliminary accord that may yet hopefully lay the foundation for a new era in Israeli-Turkish relations.

The negotiators at the talks this time were Feridun Sinirliogu, the undersecretary of the Turkish foreign ministry and Turkey’s former ambassador to Israel; Dore Gold, the director of Israel’s foreign ministry; Joseph Ciechanover, one of his predecessors, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s national security advisor, Yossi Cohen, who has since been appointed director of the Mossad.

The understanding both sides reached touched on an array of key issues.

Israel and Turkey would resume normal diplomatic relations and exchange ambassadors. Israel would pay $20 million in reparations to the families of the Turks killed aboard the Mavi Marmara during an Israeli naval raid six years ago come May. Turkey would cease legal proceedings against the Israeli commandos who stormed the ship. Turkey would expel a Hamas operative in Istanbul. Israel and Turkey would launch negotiations on the export of Israeli natural gas to Turkey via a pipeline.

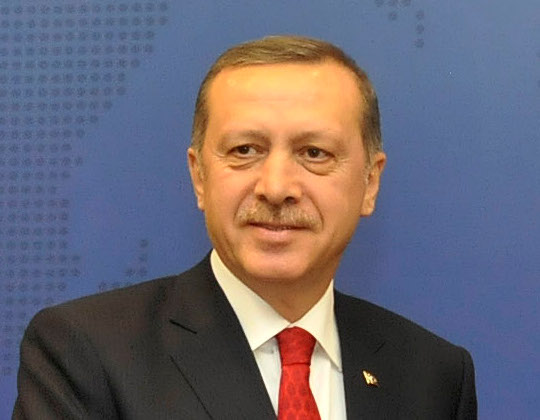

Alluding to this agreement, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan — a sharp and constant critic of Israel — said it “would be good for us, Israel, Palestine and the entire region.” On January 2, Erdogan reiterated his belief in normalization. “Israel is in need of a country like Turkey,” he said. “And we too must accept that we need Israel. This is a reality in the region.”

A reconciliation accord, however, still lies on the horizon. “There is progress,” Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu said. “But there is still no deal.” Netanyahu concurred: “We’re not there yet.”

The two major sticking points are Israel’s naval blockade of the Gaza Strip and the presence of a Hamas command center in Turkey.

Turkey, an ardent supporter of Hamas, wants Israel to lift the embargo, or, at the very least, allow Turkish products and humanitarian aid to flow into Gaza without restrictions, Turkish Customs and Trade Minister Bulent Tufenkci said recently.

Netanyahu has dismissed Turkey’s demand for the blockade to be lifted, but has not indicated whether Israel will give Turkish exports and aid preferential access to Gaza, which has been ruled by Hamas since the summer of 2007.

A year ago, Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Yaalon lashed out at Turkey, saying that Hamas has two command centers — one in Gaza and the other in Turkey. Yaalon also charged that Hamas cells in the West Bank were planning terrorist attacks under the guidance of Saleh al-Arouri, who was deported to Turkey from the West Bank in 2010. In effect, he accused Turkey of turning a blind eye to Arouri.

Under the terms of the agreement reached in Switzerland, the Turkish government would expel Arouri, who was based in Istanbul, and rein in Hamas operatives in Turkey. Netanyahu has confirmed that Arouri has been expelled, but expressed disappointment that his command center is still functioning. “Arouri’s expulsion isn’t good enough for us,” Netanyahu said. “We want to be sure there are no terror activities against Israel from Turkey.”

While the aforementioned issues are still in the discussion stage, Israel and Turkey appear to have resolved two other nagging problems.

In accordance with one of Erdogan’s demands, Israel has apologized for the Mavi Marmara incident. In 2013, Netanyahu phoned Erdogan at the urging of U.S. President Barack Obama and issued an apology which Erdogan accepted.

On May 31, 2010, an Israeli patrol boat intercepted the Mavi Marmara, a Turkish ship in the vanguard of a flotilla trying to break Israel’s siege of Gaza. When Israeli commandos boarded the Mavi Marmara, some of its passengers attacked them with clubs and knives, causing several injuries. The soldiers fired on the assailants, killing eight Turkish nationals and one ethnic Turk holding U.S,. citizenship. In response, Turkey withdrew its ambassador in Tel Aviv and cancelled a military cooperation accord with Israel. Subsequently, Israel recalled its ambassador in Ankara.

Turkey, which had been Israel’s best friend in the Muslim world, scornfully turned on Israel and demanded that Israel issue a formal apology, pay compensation to the families of the Turks who had been killed and end its siege of Gaza.

Israel refused, plunging Israeli-Turkish relations to a nadir.

Israeli and Turkish diplomats tried to defuse the tension, but to no avail. In the meantime, Erdogan — an Islamist who heads the Justice and Development Party and whose constituents fervently support the Palestinian cause — stepped up the tempo of his anti-Israel rhetoric.

Erdogan had been friendly to Israel, having played a pivotal role in mediating indirect peace talks between Israel and Syria in 2007 and having visited the Jewish state in 2005, when the then Israeli prime minister, Ariel Sharon, announced that Israel intended to pull out of Gaza unilaterally. But in the wake Israel’s invasion of Gaza in January 2009, a month after Erdogan welcomed Israel’s prime minister, Ehud Olmert, on an official visit to Turkey, he accused Israel of “state terrorism.” During the 2014 war in Gaza, Erdogan again levelled that accusation at Israel, while accusing it of “barbarism that surpasses Hitler.”

Israel’s foreign minister, Avigdor Liberman, hit back, claiming he saw no need for Israel to accede to Turkey’s three demands.

During this period of tension, Erdogan petulantly returned a Profile of Courage award the American Jewish Congress had conferred on him in 2004 for working for a peaceful resolution of the Arab-Israeli dispute and for his commitment to the Jewish community in Turkey. In an open letter to Erdogan, the then president of the American Jewish Congress, Jack Rosen, described him as “arguably the most virulent anti-Israel leader in the world.”

Last January, in the latest installment of the war of words between Israel and Turkey, Davutoglu likened Netanyahu to the Arab terrorists who attacked the headquarters of Charlie Hebdo and a kosher supermarket in Paris, claiming they were equally guilty of “crimes against humanity.”

A month later, Davutoglu said Turkey would not succumb to the “Jewish lobby” supposedly working against Turkey.

In December 2014, Hamas leader Khaled Mashaal paid an official visit to Ankara to solidify relations with Turkey. In a speech to supporters and officials of the Justice and Development Party, he declared, “Inshallah we will liberate Palestine and Jerusalem in the future.”

The comment irked the Israeli government and was symptomatic of Turkey’s dalliance with Hamas, one of Israel’s mortal enemies.

Yet even as Israel’s political ties with Turkey deteriorated, a sense of pragmatism prevailed in both capitals, with the volume of Israeli-Turkish trade increasing substantially and reaching $5.6 billion in 2014, a 50 percent increase since 2009.

Despite the problematic state of their bilateral relations, Israel and Turkey share mutual interests and threats.

Although they’re painfully at odds over the Palestinian question, with Turkey demanding a full Israeli withdrawal from the occupied areas and insisting on Palestinian statehood, they have a common enemy in the guise of Islamic extremism. Israel and Turkey recognize the threat posed by Islamic State, which seeks to establish a caliphate in the Middle East.

They also fear the specter of a resurgent Iran, which has meddled in the affairs of Syria, Lebanon and Yemen.

Israel and Turkey, too, are wary of the Russian military buildup in Syria, which has been embroiled in a civil war for more than four years now. Since Turkey’s downing a Russian jet over Turkish air space last autumn, Erdogan’s attitude to Russia’s involvement in Syria has hardened. Certainly, Israel and Turkey are concerned by the prospect of an Islamic State takeover in Syria as well as in Iraq.

With Russia having curtailed political and economic ties with Turkey in retaliation for the shooting down of the Russian aircraft, the Turkish government needs to reduce its dependence on Russia as a reliable supplier of natural gas. This is where Israel fits in. Israel’s natural gas reserves in the Mediterranean Sea could be as high as 900 billion cubic meters, which far exceed its own requirements. It’s not inconceivable that Turkey could become one of Israel’s chief customers of natural gas.

This was a prime consideration for Turkey long before its robust relationship with Russia soured. With this scenario probably in mind, Erdogan deigned to shake hands with Yosef Levi Sfari, Israel’s charge d’affaires in Ankara, in August 2014. It was the first time in six years Erdogan had taken the trouble of shaking hands with an Israeli diplomat stationed in Turkey.

Last June, in Rome, Israeli and Turkish diplomats met yet again to thrash out the issues that divide them to this day. “Its quite normal for the two countries to talk about normalization,” said Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu. “How can reconciliation be achieved without holding any meetings?”

Which is precisely the point.

Israeli and Turkish representatives will presumably keep on talking until they reach a final agreement to normalize relations. It’s an urgent matter that should not be left to fester.