Benjamin Netanyahu’s visit to Oman on October 26 caught the Middle East by surprise, but it should not have been a surprising event, even though it was the first such trip by an Israeli prime minister in 22 years.

For the past several years, Netanyahu has been saying that Israel has unofficial relations and cooperation with Arab Gulf states.

In the Knesset recently, he boasted that “Israel and other Arab countries are closer than they ever were before.” A few months ago, in Berlin, he told German Chancellor Angela Merkel that Israel is cultivating ties with Arab Sunni states against a common enemy — Iran, the preeminent Shia’a power in the region.

As he put at a press conference, “We have changes in the region that are taking place, and I think they’re very promising. We have contacts with Arab states that are developing. They developed, obviously, because of our common concern with Iran and its aggressive designs. But I think they go well beyond that.”

Netanyahu said that Israel’s Arab neighbors are aware of its technological prowess and may be interested in tapping into it. “Many Arab states recognize that Israel can contribute technologically to the development of their societies,” he said.

Israel has been trying to build relations with its Arab neighbors since its creation 70 years ago.

The first real breakthrough occurred in 1979, when Israel signed a peace treaty with Egypt. Having fought five wars with Israel since 1948, Egypt sought to disengage militarily from the Arab-Israeli dispute so as to develop its economy and improve relations with the United States.

Israel’s peace treaty with Egypt endured despite a series of crises, from the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 to the eruption of the first Palestinian uprising in 1987.

Israel signed its second peace treaty with Jordan in 1994. King Hussein of Jordan took the risk because Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization had made peace by signing the 1993 Oslo accord. Jordan was reasonably certain that the agreement would last and that the Palestinian problem would eventually be resolved.

Absent the Oslo accord, Israel definitely could not have developed relations with other Arab countries, particularly the Gulf states.

Thanks to Oslo, Israel was able to establish low-level bilateral relations with Morocco, Tunisia and Qatar. These relationships soured with the eruption of the second Palestinian intifada in September 2000.

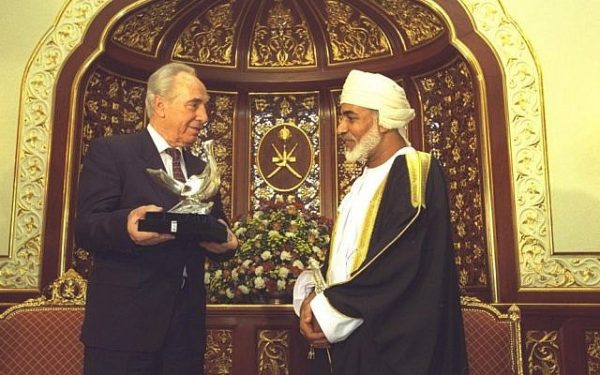

Oman participated in this post-Oslo process. Shortly after Oslo was ratified by Israel and the PLO, Oman invited the then Israeli prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, to the Omani capital, Muscat. After Rabin’s assassination in 1995, Oman’s foreign minister, Yusuf bin Alawi, arrived in Jerusalem for his state funeral. A year later, Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres, turned up in Muscat for a visit. Israel established a trade office in Muscat, but was forced to close it following the outbreak of the second Palestinian rebellion.

Oman supported the Arab League’s 2002 peace initiative, which offered Israel normalization with Arab states if it withdrew from territories captured in the Six Day War, including the West Bank, endorsed Palestinian statehood, and agreed to a just and mutually satisfactory resolution of the Palestinian refugee problem.

Israel rejected these conditions.

Netanyahu went to Oman last month at the invitation of its longtime ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said. It took both sides four months to arrange his visit. Netanyahu’s office described it in effusive language, calling it “a significant step in implementing the policy outlined by Prime Minister Netanyahu on deepening relations with the states of the region while leveraging Israel’s advantages in security, technology and economic matters.”

Following Netanyahu’s departure from Muscat, Omani Foreign Minister Yussef bin Alawi bin Abdullah expressed support for diplomatic efforts to resolve Israel’s conflict with the Palestinians and, in a telling comment, called upon Arab states to recognize Israel. As he said, “Israel is a state present in the region, and we all understand this. The world is also aware of this fact and maybe it is time for Israel to be treated the same and also bear the same obligations.”

Not surprisingly, Palestinian officials complained about Oman’s friendly treatment of and “normalization” of relations with Israel. As a result, Oman dispatched its foreign minister to Ramallah, where he met the president of the Palestinian Authority, Mahmoud Abbas, and delivered a letter to him from the sultan.

Shortly after Netanyahyu’s trip to Oman, Israel’s sports and culture minister, Miri Regev, visited the United Arab Emirates to attend the Abu Dhabi Grand Slam, an international judoka competition. Two Israeli athletes won gold medals at the tournament. At the awards ceremony, Israel’s national anthem, Hatikva, was played, moving Regev to tears. In 2017, Hatikva was banned, as was the Israeli flag, the Magen David.

And in another sign that Israel and the United Arab Emirates might succeed in forging a rapprochement, Regev, wearing a long Arab robe and a scarf on her head, visited Abu Dhabi’s Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque. Photographs of her at the mosque delighted Israelis but enraged Arabs.

“We condemn any form of normalization with Israel,” said the leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah. “The current normalization puts an end to the ِArab hypocrisy and brings down the masks of the deceitful and hypocrites.”

As Nasrallah issued this condemnation, the Israeli minister of transportation and intelligence, Israel Katz, attended a transportation conference in Muscat. It was the first time an Israeli cabinet minister had been formally invited to Oman.