With Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu having paid a landmark visit to Israel, Turkey and Israel have begun the arduous and lengthy process of patching up their often contentions bilateral relations.

Cavusoglu, the first high-ranking Turkish official to set foot in Israel in more than a decade, arrived at Ben-Gurion Airport on May 24, about two months after Israeli President Isaac Herzog visited Turkey and laid the groundwork for Cavusoglu’s constructive two-day trip.

On the eve of his departure, Cavusoglu said that Turkey — the first Muslin nation to recognize Israel — sought a “sustainable relationship” with Israel after years of mutual acrimony.

Close allies in the 1990s, when the Oslo peace process was in full swing, Israel and Turkey drifted drastically apart in recent years.

The second Palestinian uprising, which erupted in 2000, caused bitterness, as did Israel’s cross-border wars with Hamas, a Turkish ally, from 2008 onward.

The most disruptive source of animosity was the 2010 Mavi Marmara incident, during which Israeli commandos killed nine Turks aboard a Turkish vessel attempting to break Israel’s naval siege of the Gaza Strip.

Following the Mavi Marmara incident, Turkey recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv, ordered the Israeli envoy to leave, and downgraded its relations with Israel across the board.

Six years elapsed before normal diplomatic relations were restored.

“Since 1949, our relations have had its ups and downs,” acknowledged Cavusoglu last month in a reference to Turkey’s decision to establish relations with the new state of Israel.

He claimed the turbulence was caused by Israeli “violations of Palestinian rights.” As he put it, “We expect the Israeli side to respect international law on the Palestinian issue for a sustainable relationship.”

“There is a new momentum in our relations at this moment,” he added, pointing to the potential for cooperation in fields ranging from trade, energy and investment to science, technology and agriculture.

Striking a similar sanguine tone, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, a harsh critic of Israel, said, “It is clear that the way to effectively defend the Palestinian cause is to have a reasonable, consistent and balanced relationship with Israel.”

And in a letter to Herzog ahead of Israel’s Independence Day, Erdogan wrote, “I sincerely believe that the cooperation between our countries will develop in a way that serves our mutual national interests, as well as regional peace and stability.”

Tellingly enough, Erdogan condemned the Palestinian terrorist attacks that have claimed the lives of 17 Israelis and two foreign workers since March 22.

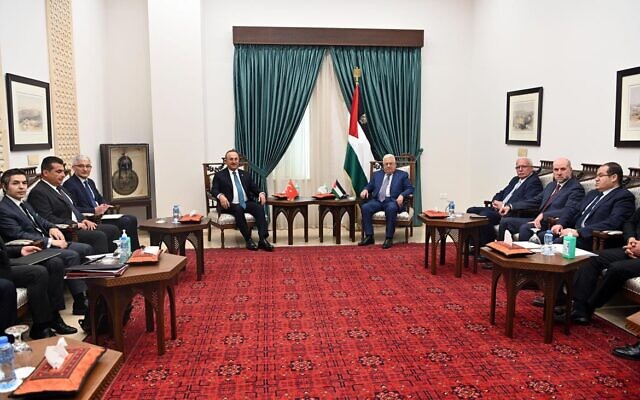

In accordance with Turkey’s sympathetic stance toward the Palestinians and its support for a two-state solution, Cavusoglu went directly to Ramallah — the seat of the Palestinian Authority — after arriving in Israel.

He met PA President Mahmoud Abbas and the PA’s foreign minister, Riyad Maliki. Later, he was given private tours of the Old City of Jerusalem and the Temple Mount, the third holiest site in Islam.

Cavusoglu told reporters that Turkey’s improved ties with Israel would not come at the expense of its relations with the Palestinians. “Our support for the Palestinian cause is completely independent of the course of our relations with Israel,” he said.

But in a nod to Israel, he said, “We believe that normalization of our ties will also have a positive impact on the peaceful resolution of the (Arab-Israeli) conflict.”

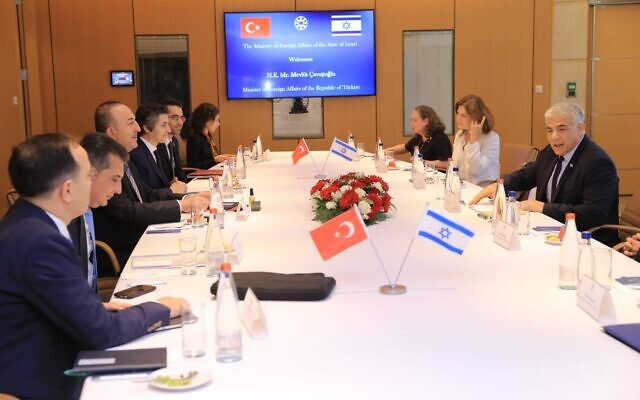

At a press joint conference, Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid said he and Cavusolglu had agreed to launch a Joint Economic Commission to expand commercial relations and to work on a new civil aviation agreement that will enable Israeli airlines to fly to Turkey, a popular destination for Israeli tourists.

After visiting the Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial and research center, Cavusoglu condemned antisemitism and Islamophobia and thanked Lapid for their “frank and candid” meetings. “We agreed that, despite our differences, the continuation of a sustainable dialogue will be beneficial, and this will be based on mutual respect to one another’s sensitivities,” he said.

Cavusoglu and Lapid discussed the issue of a mutual return of ambassadors, but it was not resolved. Turkey withdrew its ambassador in Tel Aviv in 2018 after a series of deadly clashes along the Gaza border between Israeli troops and Palestinians.

It would appear that the full restoration of relations will be a gradual process dependent on two major issues.

In all probability, Israel will not exchange ambassadors unless the Turkish government curbs the activities of Hamas operatives in Turkey. The Turkish leadership has warm relations with Hamas, but Israel has accused Hamas of planning attacks on Israelis from Turkish soil.

Turkey seeks to diversify its energy sources and looks to Israel — which is rich in natural gas thanks to fairly recent discoveries in the Mediterranean Sea — to supply its needs. Turkey, too, wants to join a consortium of nations, consisting of Israel, Greece and Cyprus, planning to build a gas pipeline from the Mediterranean to Europe.

Interestingly enough, Cavusolglu did not meet Prime Minister Naftali Bennett during his whirlwind visit, a sign that Israel’s diplomatic thaw with Turkey is far from complete. Nonetheless, Cavusolglu’s visit was a step in the right direction to improve Turkish-Israeli relations.