Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett is preparing for a crucial conversation with U.S. President Joe Biden in Washington, D.C. It will probably take place in August, after the newly-elected president of Iran, Ebrahim Raisi, assumes office.

Late last month, Biden said he hopes to meet Bennett at the White House “very soon.” His press secretary, Jen Psaki, disclosed that both sides are working to nail down an exact date.

Their first order of business will likely be the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement, which Israel opposed and from which Biden’s predecessor, Donald Trump, unilaterally withdrew three years ago in May. The Trump administration then imposed a raft of economic sanctions on the Iranian regime within the framework of its “maximum pressure” campaign against Tehran.

In reaction, Iran gradually disengaged from the agreement, enriching its stocks of uranium beyond permissible levels. On July 14, Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s outgoing president, warned it could enrich uranium to weapons-grade levels of 90 percent if it so desires.

The previous Israeli government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu not only supported Trump’s moves, but denounced Biden’s decision to return to the agreement, provided Iran complied with all its terms. As Netanyahu said, “Israel believes that going back to the old agreement will pave Iran’s path to a nuclear arsenal.”

At the very least, Netanyahu expected the United States to negotiate a much longer and stronger agreement under which Iran would be prevented from acquiring a nuclear capability for decades and would be required to curb its political and military support of Hezbollah and Hamas, both of which have fought skirmishes and wars with Israel.

Since April, Iran and the United States, plus the other signatories of the agreement — Russia, China, France, Britain and Germany — have been meeting in Vienna to discuss the possibility of reviving it. After the sixth and most recent round, Iranian Deputy Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said that progress has been made but that difficult issues have yet to be resolved.

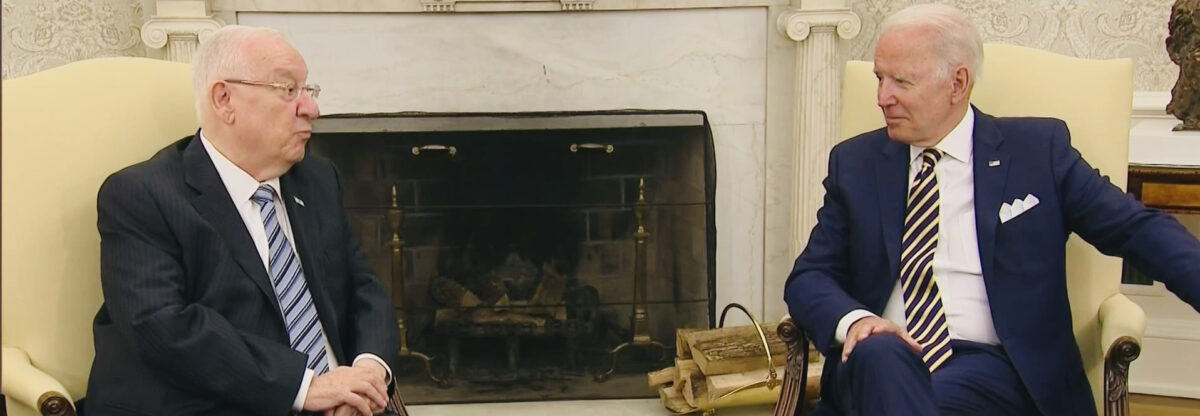

Israel and the United States agree on the basics. As Biden said recently, after hosting outgoing Israeli President Reuven Rivlin at the White House, “What I can say to you is that Iran will never get a nuclear weapon on my watch.” In response, Rivlin said he was “very much satisfied” with Biden’s position.

Bennett, in his first cabinet meeting in June, said he would hew to Netanyahu’s policy of opposing Iran’s efforts to join the nuclear club.

This is less than surprising because Bennett, a former minister of defence, is a hawk when it comes to Iran. In the past, he urged the Israeli government to openly bomb Iranian targets in retaliation for attacks carried out against Israel by Iranian proxies such as Hezbollah.

Most recently, Bennett lambasted Iran’s incoming president, who has been accused of gross human rights violations. “A regime of brutal hangmen must never be allowed to have weapons of mass destruction that will enable it … to kill … millions,” he said.

Recognizing that the United States is determined to return to the agreement, which obliged Iran to freeze its nuclear program for about 15 years in exchange for sanctions relief, Bennett hopes to convince Biden to leave the Trump-era sanctions in place.

Bennett’s rationale is that their removal would be counter-productive. He argues the United States would lose its leverage on Iran to stop or scale down its ballistic missile program and cease its destabilizing activities in the Middle East, two of the defining features of a longer and stronger updated agreement.

Of late, a procession of high-ranking Israeli officials have appeared in Washington to state Israel’s case. They include the minister of defence, Benny Gantz; the chief of staff of the armed forces, General Aviv Kohavi; the former director of the Mossad, Yossi Cohen, and Meir Ben-Shabbat, Netanyahu’s national security adviser.

It’s debatable what they achieved, but according to reports, the concerns they raised will not change the Biden administration’s plan to rejoin the agreement.

Although Israel and the United States are not on the same page with respect to various details of the Iran file, Bennett, Gantz and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid agree that Israel must avoid a public clash with the Biden administration at all costs and should express its concerns behind closed doors.

“Up to now, Israel screamed that the agreement was no good,” said Lapid last month. “The Americans screamed back that there is no better alternative and moved quickly ahead. Now, Israel will try to explain, demonstrate and prove its case to the Americans through intimate clandestine contacts. After all, we do agree on the fundamental principle that Iran must not be allowed to achieve military nuclear capabilities. We believe this way is effective, correct and serves Israel’s national security better than the previous way.”

When Netanyahu was at the helm, tensions continually flared.

During the presidency of Barack Obama, Netanyahu compared the agreement to Nazi Germany’s 1938 Munich pact with European powers and voiced his disapproval of the U.S. approach.

Several months before the agreement was signed and sealed in July of 2015, Netanyahu addressed a joint session of Congress to lambaste it. His combative style alienated the Obama administration, which proceeded sign the agreement, leaving Israel in the lurch.

This time around, Israel wants to ensure that its views are taken into serious consideration by the United States.