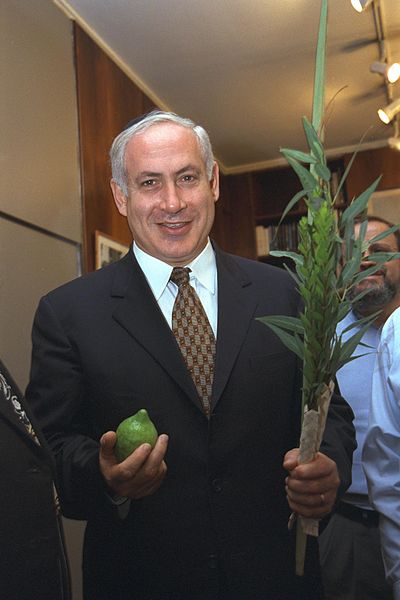

Benjamin Netanyahu is a big proponent of “economic peace” with the Palestinians.

In 2009, shortly after becoming Israel’s prime minister for the second time, he talked about the need to develop the Palestinian economy in the West Bank, claiming that job creation would benefit both parties.

He formed a special committee to improve the Palestinians’ quality of life, regarding economics as a means by which to defuse the Arab-Israeli conflict and maintain the status quo.

The committee, chaired by a senior cabinet minister, was charged with the task of creating 25 economic projects in the West Bank ranging from the establishment of industrial zones in Bethlehem and Jenin to the building of more shopping centers in major West Bank towns.

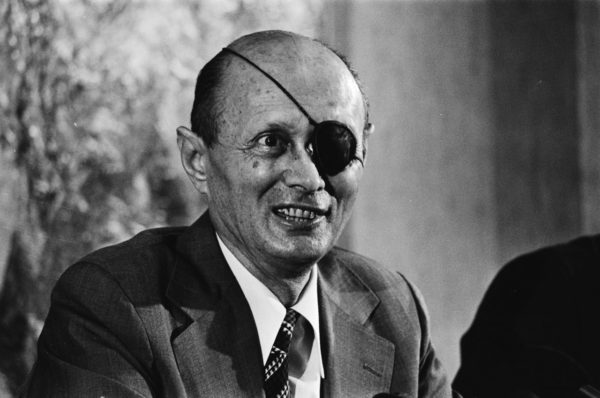

It was hardly a novel idea.

In the wake of the 1967 Six Day War, Moshe Dayan, the defence minister, unveiled the Open Bridges policy, designed to satisfy the economic needs and aspirations of the Palestinians under Israel’s rule.

Dayan, a pragmatist, believed that open borders between the occupied territories, Israel and Jordan would provide Israel with a captive market in the Palestinian areas, produce prosperity and deflect the Palestinians’ attention away from achieving sovereignty within the framework of an independent Palestinian state.

Netanyahu’s vision of economic peace falls well within these parameters.

In 2014, Netanyahu invested nine months in an effort to reach a political accord with Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. Since the utter failure of these negotiations, Israel’s relations with the PA have soured and a new wave of Palestinian violence has erupted in the West Bank, East Jerusalem and parts of Israel.

This mini uprising, which has waxed and waned since last autumn, has claimed the lives of 29 Israelis and more than 200 Palestinians and prompted Netanyahu to focus yet again on using economics to tighten Israel’s grip on the West Bank.

The West Bank’s economy is in dire straits, with the unemployment rate having reached incendiary proportions. One-third of Palestinian youths are jobless, a prescription for instability. Meanwhile, the price of basic food stuffs keeps rising, squeezing yet more of its 2.6 million Muslim and Christian inhabitants.

Corruption and mismanagement are partly to blame for the economic malaise that affects the West Bank. But Israel is also part of the problem. The security measures imposed by the Israeli army, from road closings to closures that seal off the West Bank from Israel, have curtailed freedom of movement and thereby constricted the Palestinian economy, which is already overly reliant on international assistance.

Cognizant that such measures have spawned yet more bitterness, Netanyahu recently instructed Finance Minister Moshe Kahlon to reach out to his Palestinian counterpart, Shukri Bishara, in a bid to minimize the hardships that afflict many Palestinians. In line with Netanyahu’s instructions, Kahlon has met Bishara several times in the past few months.

After their first meeting in January, Kahlon adopted a cautious tone. As he told reporters, “I will not be the one to bring peace, and I am not dealing with the diplomatic process. On the other hand, I think it is possible to advance economic issues and help change the lives of the Palestinians. This is not some lofty goal. It’s entirely possible. There can be much better, more effective economic ties between us and them, and this, in turn, may help break the deadlock, increase trust and change the overall mood.”

Thanks to their meetings, Israel agreed to transfer about $127 million in withheld customs taxes to the PA. (Under the 1994 Paris accord, a component of the 1993 Oslo agreement, Israel is obliged to hand over taxes to the PA it collects on behalf of the Palestinians. In a few instances, Israel has delayed the transfer of such funds).

Israel’s top soldier, General Gadi Eisenkot, has played a role in attempts to improve economic prospects in the West Bank. Recently, he told the Israeli cabinet that greater numbers of Palestinians should be allowed to work in Israel, where salaries are much higher. Heeding his advice, the Israeli government offered the PA 30,000 new work permits, bringing to 88,000 the number of Palestinians legally entitled to work in Israel.

These initiatives to upgrade Palestinian living standards are premised on the assumption that Palestinians with full stomachs will be more politically moderate and less prone to vent their frustrations through violence and uprisings.

But as Hillary Clinton correctly pointed out during her tenure as U.S. secretary of state, economic initiatives without a political horizon have no chance of success.

In the absence of tangible moves toward a two-state solution, the PA leadership is staunchly opposed to Netanyahu’s notion of economic peace. The Palestinians do not want to be co-opted by self-serving Israeli measures intended to deepen and prolong the occupation.

Almost 50 years have elapsed since Israel occupied the West Bank and started building a network of settlements, roads and military camps there.

At present, Israel retains full control over Area C, which comprises about 60 percent of the West Bank, and partial control over the rest of it, namely Areas A and B.

Unless Israel withdraws from the West Bank and agrees to Palestinian statehood, Israel’s plan to butter up the Palestinians with promises of prosperity will fizzle.