As Syrians slaughter each other in an increasingly vicious civil war whose death toll now exceeds 150,000 and whose outcome is still uncertain, Israel is straining to remain aloof from that conflict.

Israel’s policy of neutrality was succinctly summed up by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu last June: “Israel is not interested in intervening, as long as fire is not directed at us.”

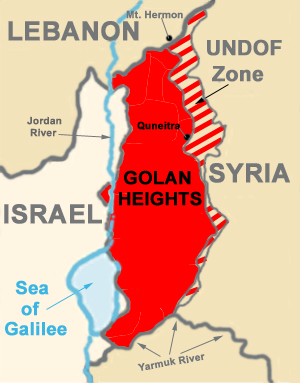

The Syrian war, however, has spilled into the Golan Heights, captured by Israeli forces in the 1967 Six Day War and annexed by Israel in 1981.

Israel has thus been sucked into the maelstrom, forced to respond militarily to acts of aggression carried out by terrorists from Syria.

Israel has also become enmeshed in the war, much to Syria’s anger, by virtue of its decision to offer medical treatment to hundreds of wounded Syrians who have been brought across the border to Israeli field hospitals on the Golan and regular hospitals in Safed and Nahariya.

And in a covert campaign to staunch the flow of sophisticated weapons from Syria to Hezbollah — which fought a three-week war with the Israeli army in the summer of 2006 — Israel has launched a series of air strikes in Syria and Lebanon to target arms convoys and warehouses.

These developments have turned the Golan, once an oasis of peace, into something of a war zone.

Israel conquered the Golan during the tail end of the Six Day War. Syria had used the rocky plateau as a base from which to shell Israel periodically. Shortly after seizing the Golan, Israel proceeded to build settlements there. The vast majority of Druze inhabitants who had lived on the Golan prior t0 hostilities elected to remain in their villages, but declined the offer of Israeli citizenship.

From 1967 to 1973, Israel and Syria clashed in periodic skirmishes. During the Yom Kippur War, which broke out in October 1973, Syria attacked Israeli positions on the Golan by land and by air, inflicting severe casualties on Israel. The Israelis turned the tide, driving the Syrians away.

Henry Kissinger, the then U.S. secretary of state, hammered out a disengagement pact after a month of indefatigable shuttle diplomacy. Israel returned Quneitra, a town near the frontier, to Syria. And a United Nations peace keeping force, the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF), was established to keep the peace along a 70-kilometre armistice line running from Mount Hermon to the Yarmuk River.

From 1974 onwards, the Golan was remarkably quiet, notwithstanding occasional flareups between Israel and Syria. With the passage of time, Israel consolidated its hold on the Golan, which supplies a good deal of its water.

Under the auspices of the United States, Israel and Syria engaged in several rounds of peace talks from the early 1990s, but they failed.

In 2011, a popular uprising erupted in Syria, with dissidents challenging the autocratic Baathist regime headed by Bashar Assad, who succeeded his father, Hafez, as president in 2000.

At first, Israel was unaffected by the fighting, but eventually, the battles spread southward and errant artillery shells and mortars began landing on the Golan, alarming Israel. More often than not, these stray projectiles caused neither property damage nor casualties.

In the meantime, the uprising has morphed into a sectarian war broadly pitting Assad’s minority Alawite/Shiite regime against a coalition of Sunni rebels. Iran, Russia, China and Hezbollah have thrown their support behind Assad. The rebels are backed by regional Sunni powers ranging from Saudi Arabia to Turkey and by Western countries like the United States, Canada, Britain and France.

As the rebels have wrested more territory from the Syrian government in the last year, the security situation on the Golan has deteriorated and Israel has beefed up its forces under the direction of Gen. Benny Gantz, the chief of staff of the armed forces.

By one estimate, more than 20 rebel groups, both secular and Islamist, currently control about two-thirds of the Syrian sector of the Golan. According to Israeli reports, only two areas, Quneitra in the center and Khader in the north, are still controlled by Assad.

Hezbollah, which has committed fighters to Syria, maintains a presence on the Golan as well.

Last June, Assad disclosed that he had made a “serious decision” to open a front with Israel along the Golan, saying he would no longer be content with only a “random firing of mortars.”

Since then, the incidents have piled up.

Shortly after Assad issued his declaration of war, several UNDOF peacekeepers were injured by unidentified gunmen. As a result, Japan, Croatia and Austria withdrew their respective contingents from UNDOF, and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon warned that the attacks threatened “to jeopardize” the durable ceasefire between Israel and Syria.

Tensions flared up with a vengeance in March.

On March 5, Israeli troops fired at two infiltrators, believed to be members of Hezbollah, planting a bomb on the Syrian side of the border fence. A few days later, a large explosive device damaged an Israeli army jeep, wounding four soldiers patrolling the adjacent border with Lebanon. On March 19, Israel pounded Syrian army positions, openly acknowledging responsibility for the first time since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war .

On March 28, in one of the most serious incidents, Israeli soldiers killed two men who had crossed into the Golan from Syria.

Blaming Assad for the attack, Israeli Defence Minister Moshe Yaalon issued a warning. “We won’t tolerate any breach of our sovereignty or attacks against our soldiers and civilians,” he declared. “We will react with might and resolve against anyone who acts against us, no matter where and when.”

Since then, the Golan has been quiet, but tensions could flare at a moment’s notice.

In accordance with its concerns regarding Hezbollah, Israel is paying close attention to its attempts to smuggle weapons and munitions from Syria into Lebanon. On Feb. 24, in the last such raid of its kind, Israeli jets hit a Hezbollah convoy near Syria’s border with Lebanon.

Usually, Israel neither confirms nor denies its role in bombing Hezbollah convoys. But in this instance, Netanyahu was determined to send a strong message to Syria and Hezbollah, saying that Israel would always interdict “the transfer of weapons by sea, air and land.”

Meanwhile, Israel is continuing to provide much-needed medical treatment to Syrians willing or able to cross the border. Recently, Yaalon said that Israel “cannot remain indifferent” to the plight of such Syrians, adding that Israel has also provided food and winter clothing to Syrian villages close to the border.

Israel’s assistance recently prompted Assad’s advisor, Bouthaina Shaaban, to accuse Israel of helping “armed gangs.”

In all likelihood, Israel will continue to treat wounded Syrians, respond to guerrilla attacks, and bomb convoys carrying weapons bound for Hezbollah.

But Israel has no intention of becoming directly embroiled in the civil war tearing Syria asunder.

Not surprisingly, the Israeli government paid no heed to a recent proposal by Syrian dissident Kamal al-Labwani — a founding member of the Syrian National Council — that Israel should establish a no-fly zone over southern Syria in exchange for keeping the Golan.

Labwani’s scheme was blasted by the rebels.

Israel has nothing to gain by aligning itself with this or that faction in the Syrian opposition. Israel’s only interest, for now at least, is the maintenance of the status quo. The civil war greatly weakens Syria, Israel’s bitter enemy, and this is to Israel’s benefit.

Yet the war is also strengthening and empowering radical Islamists fighting to overthrow Assad. They have hijacked the Syrian rebellion and, if they ever take over Syria, Israel will face immense problems.