On his last visit to Israel earlier this month, John Bolton, U.S. President Donald Trump’s national security advisor, allotted a few hours of his time for a special tour. Weather permitting, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu would show him the Golan Heights, which Israel has occupied since the Six Day War and which it annexed in 1981.

“The Golan is tremendously important for our security,” he told Bolton. “When you’re there, you’ll be able to understand perfectly why we’ll never leave the Golan and why it’s important that all countries recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan.”

“I’ve discussed this with the president,” he added in a reference to Trump.

Given the inclement weather during his trip, it’s unclear whether Bolton’s tour went ahead as scheduled. And it’s far from clear what his personal or professional opinion is of Israel’s quest to gain international recognition of its claim to this 1,800 square kilometre plateau, which overlooks the Sea of Galilee, or Lake Tiberias.

Washington’s view notwithstanding, Israel is determined to keep the Golan, which lies some 50 kilometres from the Syrian capital of Damascus. Israel’s argument is that the Golan is a strategic military asset it cannot afford to relinquish, particularly when Syria is engulfed in a civil war that has resulted in the breakdown of law and order. The war, which broke out in 2011, has claimed the lives of about 400,000 combatants and civilians and has wreaked widespread devastation.

The Trump administration has not taken a public position on this issue, fearing that its endorsement of Israel’s objective would set a precedent and perhaps encourage Israel to annex parts of the West Bank and thereby destroy the chances of a two-state solution with the Palestinians.

Last November, however, Washington sided with Israel to vote against a United Nations resolution calling for Israel’s withdrawal from the Golan, which was held by Syria until the 1967 war. Passed by an overwhelming 151-2 margin, it was opposed by only Israel and the United States. Until then, the United States had usually abstained on this resolution.

Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Danny Danon, thanked the United States “for standing with us” and declared that Israel will not “retreat” from the Golan.

Last summer, the issue was examined by Ron De Santis, the Republican chairman of a national security sub-committee in the House of Representatives who has since been elected governor of Florida. During the hearing, he argued that U.S. recognition of Israel’s annexation “would recognize the reality that the Golan is part of Israel and is vital to its national security.”

Democrats on the sub-committee opposed Israel’s annexation but recognized its presence there.

Israel conquered the Golan in the final hours of the Six Day War. Before it was captured, Israel and Syria had been embroiled in an acrimonious dispute about demilitarized zones bordering the Golan. Periodically, Syria shelled Israeli kibbutzim and moshavim in the valley below, prompting Israeli retaliatory strikes.

With the Syrians having been ejected from the Golan, Israeli settlers enjoyed a period of relative calm, which was punctuated by occasional clashes between Israeli and Syrian forces. During the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Syria temporarily captured chunks of the Golan.

In May 1974, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger was instrumental in persuading Israel and Syria to sign a disengagement agreement that left all but a small enclave of the Golan in Israel’s hands. On December 14, 1981, during Menachem Begin’s tenure as prime minister, Israel formally annexed the Golan, which is rich in water resources.

Although the Golan has remained mostly quiet since then, it has not attracted many Jewish settlers. Upwards of 25,000 Jews live in 32 settlements, the largest one of which is the town of Katzrin, population 7,000. The Golan is also inhabited by about 30,000 Druze, most of whom have retained their Syrian citizenship, but a few of whom have accepted Israeli citizenship.

The Golan is militarily important because it enables Israel to monitor Syrian army movements from afar. Since the eruption of the civil war in Syria, Israel has put the Russian-backed regime of President Bashar al-Assad on notice that it will not tolerate the entrenchment of Iranian, foreign Shi’a and Hezbollah forces on the Syrian side of the Golan.

In line with this policy, Israel bombed Iranian military targets in Syria on January 20 after the Quds Force — the foreign operations arm of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps — fired a missile at the Golan from Damascus. The Iranian missile was intercepted by the Iron Dome air defence system.

Russia, Syria’s weapons supplier and protector, has promised to keep Iranian and Iranian-supported forces a distance of at least 85 kilometres from Israel’s border. Russia has also indicated it will not recognize Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said three months ago.

Last October, for the first time in four years, the Syrian government reopened the Quneitra border crossing, signalling its victory over rebel forces in southern Syria and Israel’s de facto acceptance of Assad’s return to the area.

In general, Israel has adopted a position of neutrality toward the civil war. But until quite recently, as outgoing Israeli chief of staff General Gadi Eisenkot disclosed on January 14, Israel supplied light weapons to mainstream secular Syrian rebels operating in the vicinity of Israel’s border with Syria. As well, Israel provided humanitarian and medical aid to rebels and civilians.

Israel’s intention to keep the Golan has gone hand in hand with its willingness to trade it in exchange for peace with Syria. Virtually every Israeli prime minister, including Netanyahu, has conducted peace talks talks with Syria since the early 1990s.

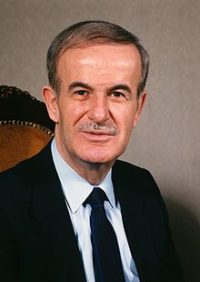

Yitzhak Rabin assured the then U.S. secretary of state, Warren Christopher, that Israel would withdraw from the Golan if its security demands were met. Assad’s late father, Hafez, was not prepared to make such commitments before a full Israeli withdrawal. Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres, tried to reach an agreement with Syria, but negotiations broke down. Netanyahu, Israel’s next prime minister, delegated his friend, the American Jewish community leader Ronald Lauder, to negotiate with the Syrians in secrecy. These talks failed.

Ehud Barak, who followed Netanyahu as prime minister in 1999, made a serious effort to break the deadlock. The talks faltered for basically two reasons. Barak refused to withdraw from the northeast corner of the Sea of Galilee, which Syria held before the Six Day War and continues to claim. Assad did not want to proceed with confidence-building measures unless he received an iron-clad guarantee that Israel would return to the pre-1967 borders. Instead, Barak offered a withdrawal to the 1923 international border.

Ariel Sharon, who succeeded Barak in 2001, did not negotiate with the Syrians. His successor, Ehud Olmert, conducted indirect negotiations with Syria through Turkey. These talks collapsed after Israel went to war with Hamas in the Gaza Strip at the end of 2008.

Following his reelection in 2009, Netanyahu conducted two rounds of secret talks with the Syrians brokered by the United States, according to Netanyahu’s former advisor, Uzi Arad. The first round, in 2009, failed, as did the second round a year later. The U.S. diplomats Dennis Ross and Frederic Hof were involved in these discussions. Since then, there have been no negotiations, direct or indirect, between Israel and Syria.

The Prime Minister’s Office denies that such talks ever took place. “Our commitment has been — and still is — keeping the Golan, a spokesman said. “We won’t give up the Golan.”

Of late, emboldened by Trump’s pro-Israel policies, Netanyahu has adopted a hard-line position toward the Golan.

In 2017, on the 50th anniversary of the Six Day War, he vowed to “forever” maintain control of it. Last October, he said, “Israel on the Golan is a fact that the international community must recognize, and as long as it depends on me the Golan will always remain under Israeli sovereignty because otherwise we would have Iran and Hezbollah on the shores of the Kinneret (the Sea of Galilee).”

Netanyahu’s comments notwithstanding, Syria is bent on recovering the Golan. Addressing the United Nations General Assembly last September, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Muallem said, “Just as we liberated southern Syria from terrorists, we are determined to fully liberate the occupied Syrian Golan to the lines of June 4, 1967.”