When it comes to its foreign policy towards Russia and Ukraine, Israel walks a diplomatic tightrope.

The Jewish state must take into consideration all kinds of factors: its relationship with both countries, one of them a great power; its alliance with the United States, which strongly backs Kiev in its struggle with Moscow; and the effect of its policies on the situation of the still substantial Jewish communities in both of the former Soviet states.

This has led to some uncomfortable situations.

A Defense Ministry-approved deal to sell drones to Ukraine was vetoed by a Foreign Ministry special panel amid fears Russia would disapprove, Israel’s Channel 2 reported on Sept. 15. Jerusalem was concerned a drone sale to Ukraine would anger Moscow.

When Russia annexed the Crimea in March, Jews in the region were divided in their attitudes. Most Crimean Jews, Russian speaking, supported the move, while those in Ukraine were opposed. Jews in Russia on the whole supported the move.

The 193-member UN General Assembly on March 27 passed Resolution 68/262 by a vote of 100 to 11 to denounce the Crimean referendum that paved the way for the absorption of the peninsula into Russia. Another 58 countries abstained, while the remaining 24 did not vote.

Israel did not take part in the vote, using a strike by staff at its Foreign Ministry as a pretext for the abstention.

“Our basic position is that we hope Russia and Ukraine will find a way as quickly as possible to normalize relations, and find a way to talks, and to solve all the problems peacefully,” remarked Israel’s Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman at a Jerusalem news conference in April.

The United States was not happy with Israel. “We were surprised Israel did not join the vast majority of countries that vowed to support Ukraine’s territorial integrity in the UN,” U.S. State Department spokesperson Jen Psaki said at a briefing after the UN vote.

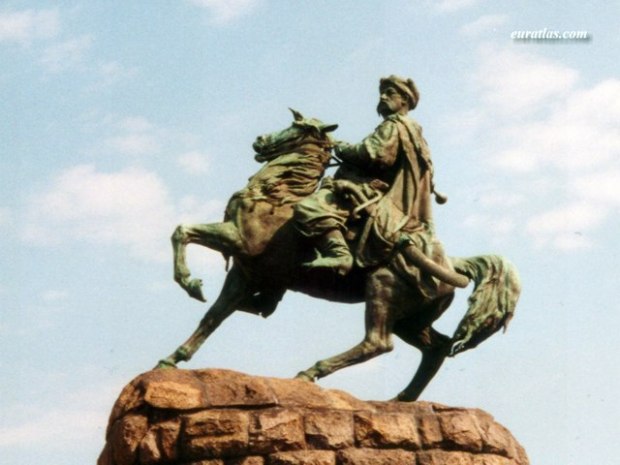

Historically, Jews have less than fond memories of Ukraine, traditionally a hotbed of antisemitism. In 1648-1649 the Cossack Hetman Bogdan Chmielnicki led a peasant uprising against Polish rule in the Ukraine which resulted in the destruction of hundreds of Jewish communities and the deaths of at least 100,000 Jews.

After World War I, Symon Petliura’s Ukrainian nationalists, fighting the newly-formed Soviet armies, were involved in pogroms that killed about 50,000 Jews. And during the Holocaust, Nazi death squads, and their Ukrainian collaborators, murdered 900,000 Jews.

The radical elements of Ukraine’s far-right nationalist politics, which rose to the fore during Ukraine’s overthrow of President Viktor Yanukovych in February, are also working in Russia’s favor.

Russian antisemitism was less virulent. As well, those Israelis with long memories recall the Soviet Union’s role during the struggle to establish the state.

Moscow voted for UN General Assembly Resolution 181 in November 1947 to partition Palestine into Arab and Jewish states, recognized Israel de jure almost immediately in May 1948, and allowed its allies to provide arms to the new country.

As well, the Soviets in December 1948 voted against UN General Assembly Resolution 194 on the so-called “right of return” of Palestinian refugees to their homes.

Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, a hawk, is himself Soviet-born. He comes from Chisinau (Kishinev), in Moldova, and is the founder and leader of the Yisrael Beiteinu party, whose electoral base consists of immigrants from the former USSR.

Lieberman, who immigrated to Israel in 1978, lives in the West Bank settlement of Nokdim. He admires Russian President Vladimir Putin, and in December 2011 appeared with him just days after a contested legislative election in Russia. In turn, the Russian leader visited Israel in June 2012.

“We are very happy that people from the Soviet Union build such a brilliant political career,” said Putin in 2009, when Lieberman was first appointed to the position by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Speaking to a group of rabbis from Israel and Europe in July, during the latest Gaza war, Putin said, “I support Israel’s struggle, which is intended to protect its citizens.” (After all, Putin has his own terrorists to worry about, in Chechnya, Dagestan, Ingushetia, and elsewhere.)

Of course America remains Israel’s lifeline, its main economic, ideological, and political ally. Still, in the final analysis, Israel, as a beleaguered state now surrounded on virtually all sides by chaos and violence in neighboring countries, must hedge its bets.

In a Middle East that is exploding, Israel can’t depend on just one great power ally. The recent Gaza war, and the different approaches to Iran’s nuclear ambitions, has exposed rifts between Netanyahu and U.S. President Barack Obama.

Meanwhile, on Sept. 16 Ukraine’s parliament passed legislation to grant special status to the rebellious east as part of a peace deal, hopefully a war with Russian-backed separatists that has killed more than 3,000 people.

It grants three years of self-rule, including the election of local councils, in parts of the war-torn east and calls for local elections in November. It also allows for local oversight on court and prosecutor appointments and local control of police forces. And it gives the region the right to use Russian as an official language.

Israeli diplomats may now have less to worry about.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.