As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu prepares to visit Africa next week, it’s a good time to recall the ups and downs of the Jewish state’s almost seven decades long relationship with the vast continent it borders to its southwest.

His trip to four East African countries, the first to the continent by an Israeli leader in more than two decades, will begin with a ceremony in Entebbe, Uganda, marking the 40th anniversary of the hostage rescue in which his brother, Yonatan, died. He will then travel to Kenya, Rwanda and Ethiopia.

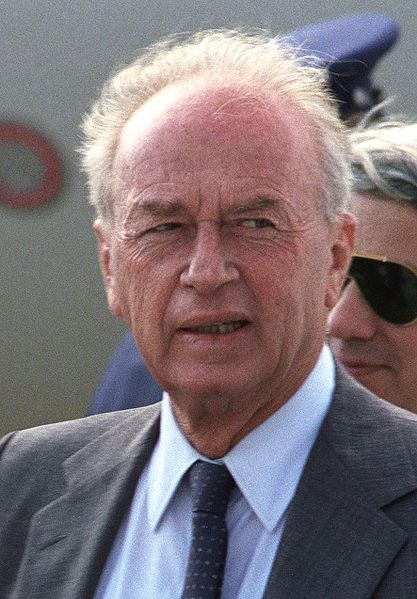

The last Israeli prime minister to visit an African country was Yitzhak Rabin, who went to Morocco in 1994.

Operation Entebbe was a daring operation on July 4, 1976 to liberate Israeli hostages held in Uganda’s main airport by Palestinian terrorists. They were passengers aboard an Air France plane, en route from Tel Aviv to Paris, which had been hijacked by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

Uganda was at the time ruled by the murderous tyrant Idi Amin, who was a supporter of the Palestinian cause.

Natanyahu’s trip is part of a growing alignment between Israel and sub-Saharan African states. Jerusalem is searching for new allies as its traditionally close ties with Europe cool, and both it and African states face a common threat from radical Islamist groups. Not coincidentally, all four of these African states are Christian-majority countries.

He also needs their cooperation to curtail illegal migration of Africans into Israel.

Uhuru Kenyatta, Kenyan president, was in Israel in February, the first visit by a Kenyan leader since 1994. Ghana’s foreign minister, Hanna Tetteh, was in the country a month later and discussed deepening economic and security co-operation, “especially the fight against Islamist terrorism.” During her visit, Netanyahu also expressed “Israel’s expectation of continued change in voting patterns at the UN in light of anti-Israel decisions in international bodies.”

Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf travelled to Israel in June to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of Haifa for her work in promoting women’s equality and other human rights issues.

Israel and Africa’s “rediscovery should have happened a long time ago,” Netanyahu remarked at a meeting in the Israeli Knesset with Israeli MPs and 13 African ambassadors in February. “Israel is coming back to Africa; Africa is coming back to Israel.”

Israel is willing to help Africa defeat Islamic terrorism, he vowed. “It threatens every land in Africa,” he told them. “Its nexus is in the Middle East, but it is rapidly spreading. It can be defeated. It can only be defeated if the nations that are attacked by it, make a common cause.”

During Kenyatta’s visit, the prime minister noted that the two countries are allies in the war against terrorism.

The East African country has suffered a number of attacks by al-Shaabab Somali militants, including the attack on Sept. 21, 2013 on the Westgate Mall in Nairobi that left 67 people dead. A private Israeli firm is now in charge of security at the shopping mall.

Israeli officials speak of building a “wall of friendly countries” along a band of Africa that stretches from the Ivory Coast, Togo and Cameroon in the west to Rwanda and Kenya in the east.

African countries want Israeli know-how in cyber security and homeland security at a time when the threat of Islamic extremism has left governments in search of advanced defence technology. Israel’s intelligence and military expertise could help African states dealing with groups such as Boko Haram, al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda.

The Foreign Ministry’s deputy director general for Africa, Yoram Elron, noted that “Africa, which has today one of the highest growth rates in the world, presents many business opportunities in areas Israel has extensive expertise, such as agriculture, telecommunications, alternative energy and infrastructure.”

A press release prior to Netanyahu’s departure detailed several steps geared at expanding economic ties. The first point calls for Israel and African nations to establish “unprecedented cooperation” with the World Bank aimed at encouraging development projects in Africa.

The plan also proposes the establishment by Israel of four centers for excellence in Uganda, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Rwanda, with the goal of increasing Israeli exports to these countries.

It also seeks to establish a mechanism to make it cheaper for Israeli companies to do business in Africa, as well as steps to improve cooperation in the fields of health and science.

At the launch of a new Israel-Africa caucus in the Israeli parliament last February, Knesset speaker Yuli Edelstein mentioned that ties with the continent have long been an Israeli priority.

In the first two decades of Israel’s independence, the nation worked assiduously at establishing a presence in newly sovereign African countries. After all, the Jewish state had itself emerged from colonial control in 1948.

The first Israeli embassy in Africa was opened in Accra, Ghana, when that country attained independence. Not long afterwards, then foreign minister Golda Meir made a five-week trip to Africa and had the first high-level discussions with African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, William Tubman, and Felix Houphouet-Boigny.

She believed that Israel had experience in nation-building that could be a model for the Africans. “Like them, we had shaken off foreign rule. Like them, we had to learn for ourselves how to reclaim the land, how to increase the yields of our crops, how to irrigate, how to raise poultry, how to live together, and how to defend ourselves,” she wrote in her autobiography My Life.

Israel could be a role model because it “had been forced to find solutions to the kinds of problems that large, wealthy, powerful states had never encountered.”

Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion told the Knesset in 1960, “Our aid to the new countries” is not a matter of philanthropy. We are no less in need of the fraternity of friendship of the new nations than they are of our assistance.”

In the late 1950s and 1960s, Israel helped establish agricultural cooperatives, youth training programs, medical infrastructure and joint industrial enterprises in a number of sub-Saharan countries. In 1962, Newsweek called the Israeli program “one of the strangest unofficial alliances in the world.”

But all that began to change as the Israeli-Arab conflict drove a wedge between African countries and the Jewish state in the 1960s. Pressure from Arab nations, accentuated by the 1967 and 1973 wars between Israel and its neighbors, led most African states to cut their relations with Jerusalem.

Between June 12, 1967, and November 13, 1973, 29 African states broke relations with Israel. Many also gave the Palestine Liberation Organization diplomatic status. After the Yom Kippur War, only Malawi, Lesotho and Swaziland maintained full diplomatic relations with Israel.

But since the 1980s, diplomatic relations with Sub-Saharan countries have been gradually renewed. By the late 1990s, official ties had been re-established with forty countries south of the Sahara, including a number of Muslim-majority states.

The Palestinians are not happy about Netanyahu’s trip, their media reminding Africans that the Uganda-Kenya region when under British colonial rule was one of the territories that the Zionist movement considered as a site for Jewish colonization in 1903, so the Ugandan and Kenyan people today could have been “as oppressed” as the Palestinian people are today.

They also chided Israel for using a “brethren of suffering” approach to Rwanda by drawing parallels between the Holocaust and the 1994 genocide in that country.

Ironically, Israel’s relations with South Africa, the continent’s second-largest economy and home to its largest Jewish community, remain strained.

The ruling African National Congress has strong ties with the Palestinians and compares the Israeli government to the white apartheid regime. The “Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions” movement, modelled on the international anti-apartheid movement, has a strong following there.

Henry Srebrnik is a professor of political science at the University of Prince Edward Island.