Hamas, the governing authority in the Gaza Strip for the past 16 years, has escalated its bitter conflict with Israel beyond Gaza’s borders.

This is a provocative and potentially dangerous development that bodes well neither for Israel nor Hamas.

Since last May’s cross-border war in and around Gaza, the fourth in 13 years, Hamas has aggressively threatened to bombard Israel with rockets and thereby ignite a fresh round of warfare if the Israeli government “violates” the Temple Mount complex and East Jerusalem.

Hamas, which is supported by Iran, has issued these threats despite the loss of lives and property destruction that the last war in Gaza caused.

Although Israel is by far militarily superior to Hamas in every conceivable respect, the Israeli government has not ignored or dismissed Hamas’ bluster.

In recent weeks, Israel has taken certain steps to tamp down the possibility of a new wave of violence on the Temple Mount or the prospect of another Gaza war. In effect, Hamas has established a new form of deterrence against Israel. Whether it endures is open to debate.

Last month, in tacit conformity with Hamas demands, Israeli police prevented a group of right-wing Jewish extremists from provocatively entering the Old City of Jerusalem through the Damascus Gate, which leads to the Al-Aqsa mosque at the Temple Mount, or, as the Palestinians call it, the Haram al-Sharif.

And in a second precautionary move motivated by its desire to nip trouble in the bud, Israel closed the courtyards of the mosque to Jews from April 22 until the end of Ramadan in early May.

Hamas, an Islamic fundamentalist organization that rejects Israel’s very existence, has inserted itself in the perennially volatile Temple Mount issue so as to extend its influence in the West Bank and to weaken its secular rival, the Palestinian Authority, which is headquartered in Ramallah and which cooperates with Israel in containing terrorism.

Hamas has confronted Israel over the Temple Mount at a moment when its rocket launchings from Gaza have diminished significantly and the border region is fairly quiet.

Hamas’ assertive position toward the Temple Mount comes at a time when record numbers of Palestinian day workers are crossing into Israel and the Arab state of Qatar is pouring substantial sums of money into Gaza so that civil servants can be paid and reconstruction projects can proceed or continue.

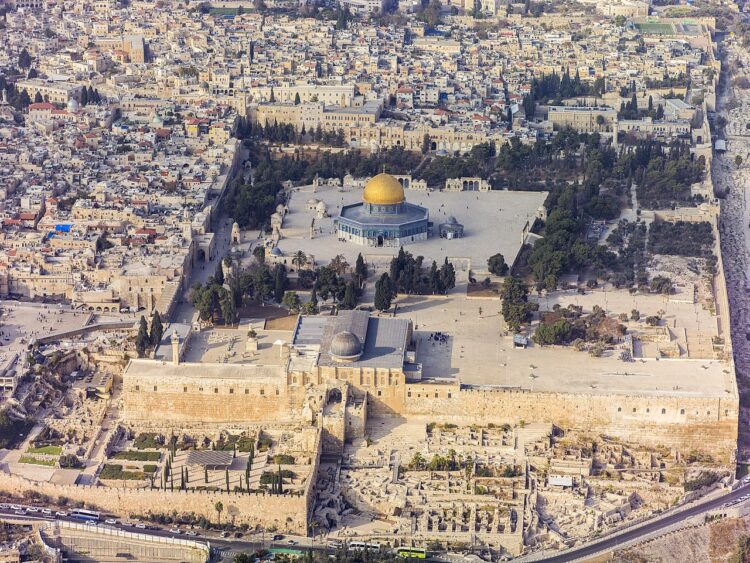

The Temple Mount, regarded as sacred ground by Jews and Muslims alike, is the holiest site in Judaism and the third holiest in Islam. It has been a constant flashpoint in Israel’s tortured relations with the Palestinians since its capture by the Israeli army during the Six Day War in 1967.

Jordan, its official custodian, administers the Temple Mount, but Israel is in charge of day-to-day security. Under a status quo agreement worked out in the wake of the Six Day War, Israel permits only Muslims to worship at the Temple Mount, but Jews and Christians are allowed to visit at specific times.

Israel annexed eastern Jerusalem in 1967, amalgamating it with the western half, and proceeded to declare the entire city as its indivisible and eternal capital. Several counties, including the United States, have recognized Israel’s annexation, but Palestinians regard East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza.

The bitter conflict over Jerusalem’s final status, one of the thorniest in Israel’s dispute with the Palestinians, periodically erupts into violence at the Temple Mount.

As Muslims in Jerusalem marked Ramadan in April, clashes pitting Palestinians against Israeli police broke out at the Temple Mount. Palestinian rioters threw stones at police, who responded with tear gas, rubber bullets and sound grenades, resulting in injuries on both sides.

A similar pattern of rioting erupted at the Temple Mount last year. The violence then was ignited by Israel’s planned eviction of Palestinian families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in eastern Jerusalem.

These incendiary incidents prompted Hamas — the Islamic Resistance Movement — to fire rockets at Jerusalem. In quick succession, Israeli aircraft bombed Hamas military bases and weapons workshops in Gaza. Hamas retaliated, precipitating an 11-day war dubbed by Hamas as The Sword of Jerusalem.

Until that turning point, Hamas’ interactions with Israel were strictly confined to Gaza, from which Israel withdrew unilaterally in 2005 and which has been subjected to an Israeli land, sea and air blockade since 2007.

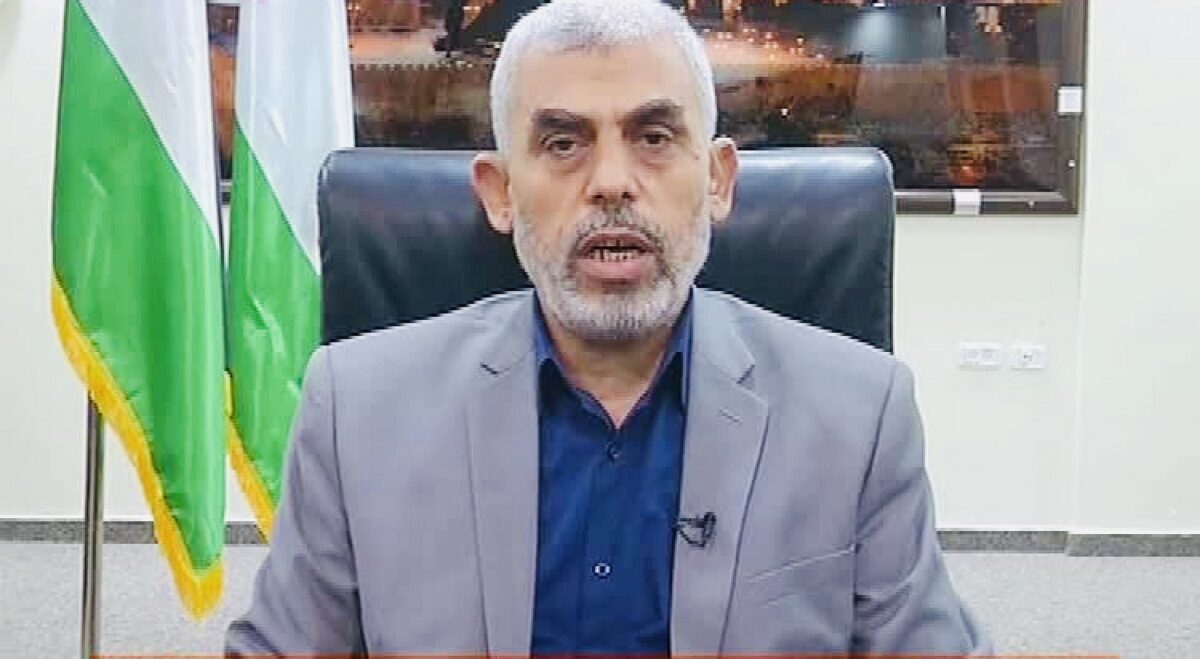

With tensions rising in Jerusalem once again, Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, a former Israeli prisoner, warned Israel that a “regional, religious war” would break out if Israel “violated” the Temple Mount. Sinwar has accused Israel of seeking to partition the Temple Mount, destroy the Al Aqsa mosque, and build the third temple in its place. “Al Aqsa is in danger,” he said recently.

Sinwar, too, claims that Israel has violated Hamas “red lines” by announcing closures in the West Bank and by imposing collective punishments and a variety of security measures designed to deter terrorists.

As tensions on the Temple Mount flared last month, Israel was struck by a series of terrorist attacks in Beersheba, Hadera, Tel Aviv, Elad and outside the gates of Ariel, a Jewish settlement deep inside the West Bank. These attacks have claimed the lives of 19 Israelis since March 22. The perpetrators were both Arab citizens of Israel and Palestinian Arabs from the Jenin region of the West Bank.

The two Palestinian terrorists who killed three ultra-Orthodox Jews in Elad a few days ago, Assad Yousef al-Rifai and Subhi Emad Subhi Abu Shqeir, were lauded as heroes by Hamas. It’s unclear whether they are Hamas members, but in all probability, they were inspired by Hamas rhetoric.

Much to Israel’s anger, Sinwar has praised these terrorist incidents and urged Palestinians to murder Israelis. “Let everyone who has a rifle ready it,” he declared. “If you don’t have a rifle, ready your cleaver, an axe or a knife.”

Although Sinwar has not taken credit for most of the latest attacks, Hamas claimed responsibility for the murder of Vyacheslav Golev, an Ariel security guard, on April 29. “This operation comes within a series of responses to the defiling of our Al Aqsa and aggression against it,” said Hamas’ armed wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassem Brigades, in a statement on May 2.

Israeli officials have since warned Sinwar that he and other Hamas leaders may be singled out for assassination because they have encouraged terrorism.

Two days ago, in reaction to Israel’s threat to resurrect its policy of targeted killings, Hamas warned Israel that it can resume its campaign of suicide bombings and launch rockets at its major cities.

Israel would prefer to avoid a new round of fighting, but a fifth Gaza war may well be inevitable.