For a relatively brief moment after World War II, the Zionist movement and the newly-formed state of Israel enjoyed the unanimous support of the Soviet Union, its East European allies and the United States.

This short-lived interregnum was a unique period when, as Jeffrey Herf observes in his superb book, Israel’s Moment: International Support for and Opposition to Establishing the Jewish State, 1945-1949 (Cambridge University Press), “the antifascist passions (of the war) had not completely given way to and overlapped with the … contrary priorities of the Cold War.”

Much to the indignation of the Arab Higher Committee — the representative body of the Palestinians — and of the Arab League — the organization representing the Arab world — the United States and the Soviet Union each supported United Nations Resolution 181, the partition plan of November 29, 1947, which allotted space in Palestine for a Jewish and an Arab state.

As Herf correctly points out, their endorsement of Zionism turned out to be “the last political expression of what remained of the anti-Nazi coalition” of the war.

It is often forgotten today that, while the United States was the first nation to offer Israel de facto recognition, the Soviet Union was the first country to recognize Israel on a de jure basis.

Harry Truman, the president of the United States, was morally and politically committed to Jewish statehood, but the State Department, the Defence Department, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Central Intelligence Agency regarded the formation of a Jewish state as contrary to American security interests in the Middle East. They believed that a pro-Zionist stance would benefit the Soviet Union, undermine America’s containment-of- communism policy, and block Western access to Arab oil and markets.

As Herf writes, “The view that the Zionist project opened a dangerous opportunity for Soviet expansion in the Middle East became widespread among diplomats, military officials and intelligence analysts” not only in the United States but in Britain, which held the League of Mandate in Palestine from 1922 to 1948.

Anti-Zionist “Arabists” in the U.S. and Britain failed to squelch the movement toward Jewish statehood, but they attempted to replace the partition scheme with a trusteeship. They also convinced Truman to impose an arms embargo against Israel during its War if Independence, and succeeded in keeping the U.S. connection to Israel cool and distanced until the early and mid-1960s, when the occupants of the White House were John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Baines Johnson.

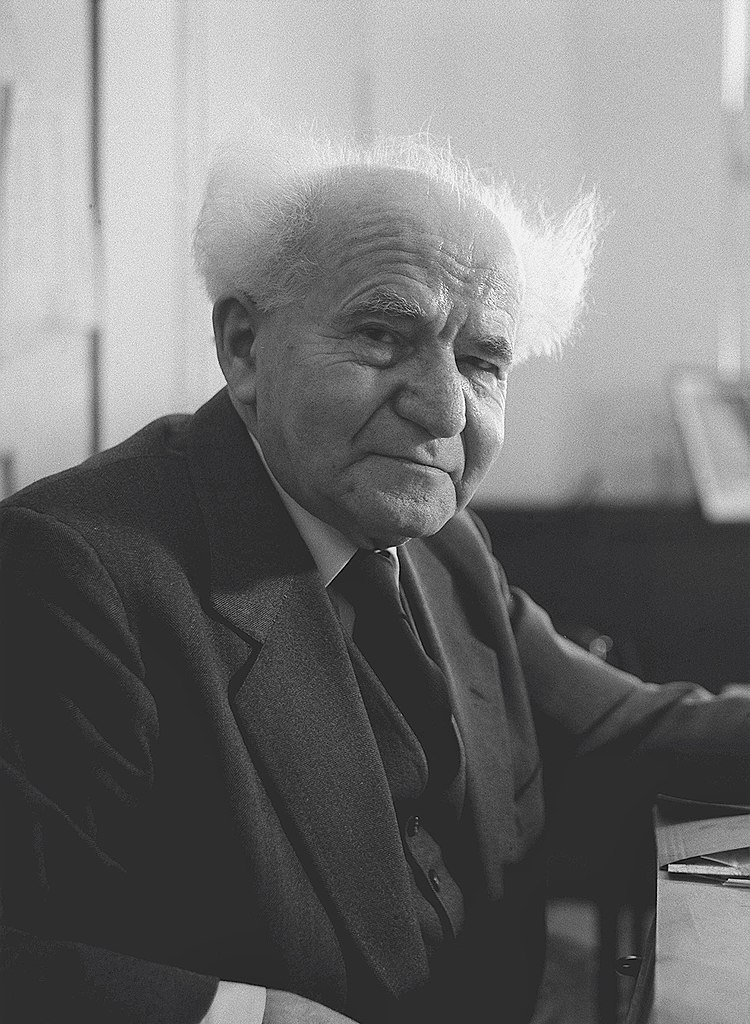

The first Israeli prime minister, David Ben-Gurion, realized that U.S. policy operated on two diametrical tracks. In 1949, he told the U.S. ambassador to Israel, James McDonald, that if Israel had been dependent on the United States for survival, it would have been defeated by the Arabs.

The Soviet Union, which had been anti-Zionist until then, switched course and viewed the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine as an instrument to reduce or eliminate British and American power in the region. During this period, communist Czechoslovakia, with Joseph Stalin’s blessing, was the only country willing to sell weapons to the Jewish Agency, the preeminent body in Palestine’s Jewish community.

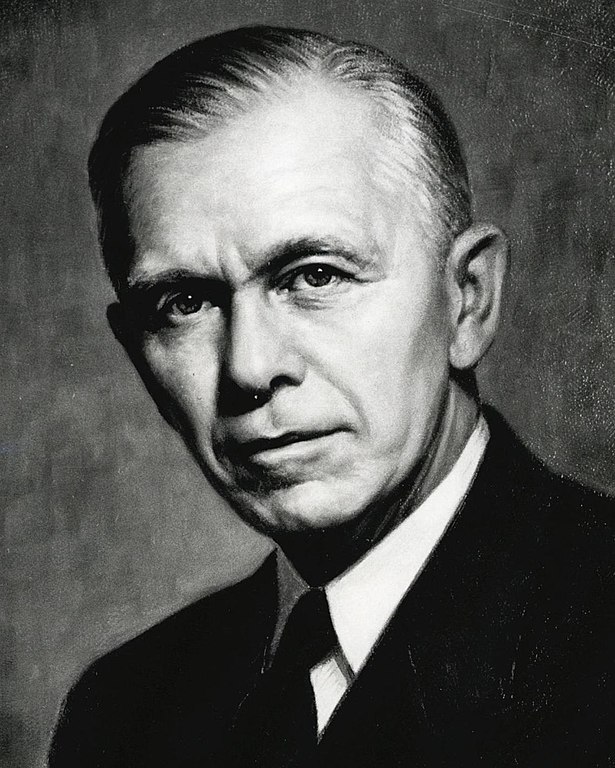

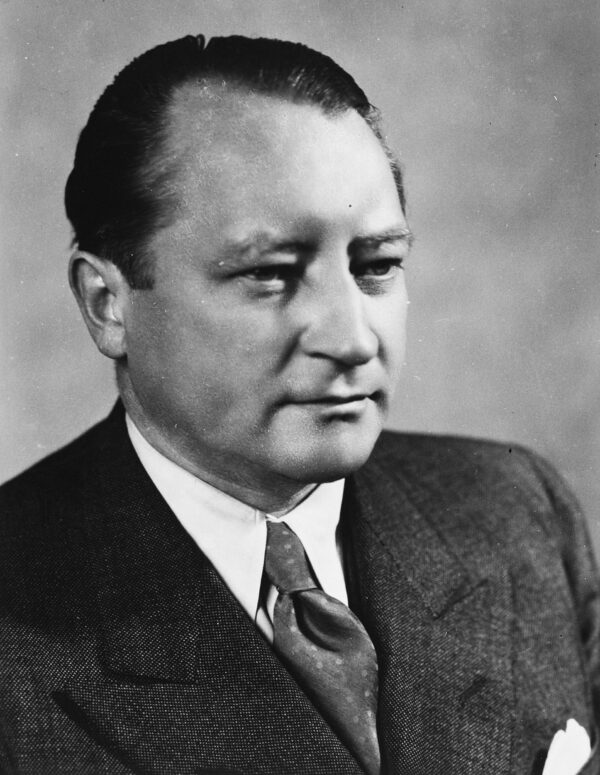

The Czech-Israel connection reinforced the jaundiced opinion of U.S. decision-makers, such as Secretary of State George Marshall and Secretary of Defence James Forrestal, that Israel’s ties to the Soviet bloc were suspicious. Much to their probable surprise, Israel’s relations with the Soviet Union soon deteriorated, with France becoming Israel’s closest ally from 1949 until 1967.

Herf, a professor of modern history at the University of Maryland, reminds a reader that liberals and leftists rallied around the Zionist cause during Israel’s “moment” in the mid-and late 1940s. Among the pro-Zionist voices were the journalists I.F. Stone and Freda Kirchwey, both of whom wrote for The Nation. For them, Israeli statehood was “a logical culmination” of anti-Nazi and anti-fascist wartime passions.

Pro-Zionist sentiment in the United States ran deep. The election platforms of both the Democratic and Republican parties in 1944 called for an end to British immigration restrictions in Palestine. In Congress, Senator Robert Wagner and Congressman Emanuel Celler, both of New York State, were among the most vocal advocates of Jewish statehood.

The State Department, however, diverged from this position. Its policy planning division, led by George Kennan, the architect of Soviet containment as enunciated in his 1946 Long Telegram, articulated a policy opposed to partition in Palestine and in favor of an arms embargo with respect to Israel and the Arab states.

Loy Henderson, the director of the State Department’s division in charge of Middle Eastern affairs, argued that U.S. support for partition would undermine its relations with Arabs and Muslims. His colleague, William Eddy, a former president of Dartmouth College and the ambassador to Saudi Arabia from 1944 to 1946, objected to a “theocratic, racial Zionist state.” Herf speculates that Eddy may have been the first Western diplomat to equate Zionism with racism.

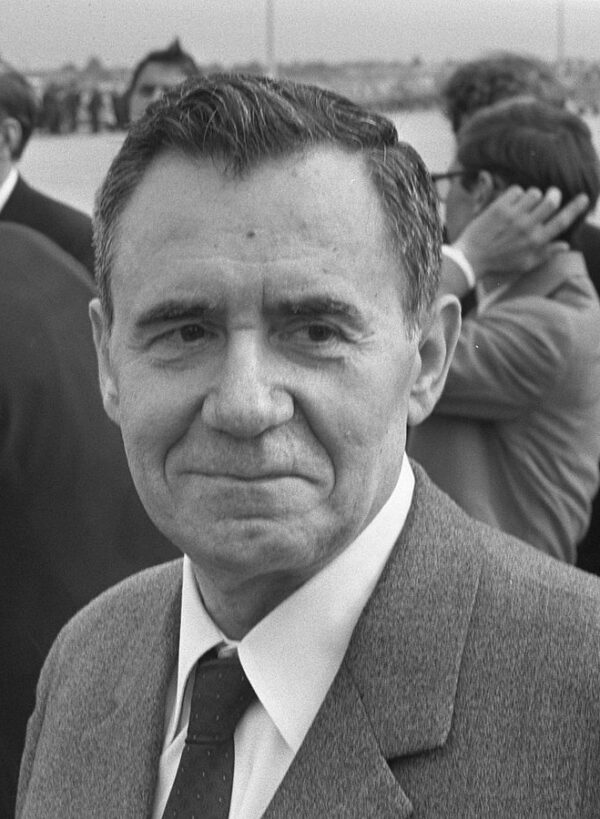

Dean Rusk, the director of the State Department’s Office of United Nations Affairs and a future secretary of state, rejected partition and favored a trusteeship under the auspices of the United States.

Sumner Welles, who had been under secretary of state from 1937 to 1943, was one of the few Americans in the U.S. national security apparatus who backed Jewish statehood.

Another pro-Zionist official, Clark Clifford, was Truman’s special assistant. Clifford advised Truman that a succession of presidents since Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge had endorsed the establishment of a Jewish state, and predicted that the new state would be strongly oriented toward the United States. He urged Truman to lift the arms embargo and to stop impounding the passports of Americans who had served in a Jewish military force in Palestine.

Clifford’s influence on U.S. policy was mixed, suggests Herf. While he persuaded Truman that partition was a desirable outcome, the Truman administration rejected “excessive Israeli claims to further territory within Palestine,” and urged Israel to offer “territorial compensation” for lands it had captured beyond the boundaries of the 1947 United Nations resolution.

As well, the United States supported a United Nations plan, advanced by Count Folke Bernadotte of Sweden, that would have given the Negev to Transjordan, converted Haifa into a “free” port and internationalized Jerusalem.

The Soviet Union was Israel’s strongest supporter during this fraught era. On May 14, 1947, the Soviet ambassador to the United Nations, Andrei Gromyko, stunned the United States and Britain by announcing that Moscow would support the partitioning of Palestine into separate Jewish and Arab states if Jews and Arabs could not agree on a binational state. And the Soviet Union rejected the Bernadotte plan as an imperialist plot.

“Gromyko’s reference to the Jews as ‘a people,’ with rights of national self-determination and a historical link to the territory of Palestine, went much further than the U.S. delegation did in support of Zionist goals,” writes Herf.

Poland, a Soviet ally, was one of the most passionate supporters of Jewish statehood. On the eve of the passage of United Nations Resolution 181, Oskar Lange, the Polish ambassador, explained that Poland’s position was based on three factors. The major role that Polish Jews had performed in the development of the Yishuv, the Jewish community of Palestine. The extermination of three million Polish Jews during the Holocaust, which established a bond of suffering between Poles and Jews. The affinity of Poland with the national aspirations of the Jewish people.

Czechoslovakia was extremely important in Israel’s survival, having sold the Yishuv $28 million worth of arms and munitions, a sum equivalent to $300 million today. The package included tens of thousands of rounds of bullets, vast quantities of bombs, 24,500 rifles, 5,000 machine-guns, 12 tanks, 25 Messerschmidt fighter planes and 59 Spitfire aircraft.

Ben-Gurion, in 1968, told an Israeli journalist that Czech arms deliveries “saved” Israel during the first months of the War of Independence. But the Czechs who made this possible, including foreign minister Vladimir Clementis, paid dearly for their pro-Zionism. In 1952, during the notorious Slansky show trial, he was arrested, having been accused of being a member of a “Titoist, Trotskyist, Zionist conspiracy.” He was hanged, along with ten others.

The Czechs, of course, took their anti-Zionist cue from the Soviet Union, which turned against Israel in 1949 as Stalin launched his anti-cosmopolitan/antisemitic purges. “In doing so, the Kremlin did all it could do to suppress the public memory of the important era of Soviet bloc support for Zionist aspirations,” says Herf.

Over the next few decades, the Soviet Union presented itself as the champion of the Arab/Palestinian cause and tarred Israel as a tool of Western imperialism in the Middle East.

The Labour Party in Britain, upon assuming office in 1945, reversed its pro-Zionist policy, with Prime Minister Clement Attlee and Foreign Minister Ernest Bevin determined to preserve British influence in the Middle East. As a result, Britain abstained on the 1947 partition resolution.

In France, meanwhile, a broad range of Gaullists, communists, socialists and radicals came out in support of Zionist objectives in Palestine. The Foreign Ministry, focusing on the Soviet threat and French interests in the Arab world, opposed Jewish statehood. Yet France was among 33 countries that voted for the 1947 partition plan, which was opposed by 13 nations, including Cuba, Greece, India and Turkey. And in the intervening years, France was Israel’s most important military ally, as Herf reminds a reader.