A year ago, on Nov. 14, Israel launched Operation Pillar of Defence, an eight-day offensive designed to restore a measure of peace along its volatile border with the Gaza Strip.

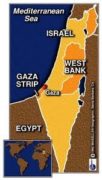

Israel and the Palestinians promised to observe a ceasefire in the wake of the fighting, and although there has been a significant drop in the number of reported incidents since then, tensions continue to flare periodically, and Gaza is still Israel’s hottest border.

The truce crumbled shortly after it was signed, but lately, it has been subjected to further stress and strain.

On Oct. 27, two mortar shells fired from Gaza landed in the western Negev, causing no injuries or damage.

A week earlier, the Israeli army discovered and destroyed a tunnel running into Israel. The Palestinians use these tunnels to launch attacks inside Israel. In 2006, they used a similar tunnel to attack an Israeli border post, killing two troops and kidnapping the soldier Gilad Shalit, who spent five years in captivity before being released in a prisoner exchange in 2011.

On Oct. 28, two rockets were fired into Israel’s southern coastal region, setting off warning sirens in Ashkelon and surrounding areas.

These incidents led the Israeli Air Force to bomb rocket launchers in Gaza and prompted Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations, Ron Prosor, to lodge a complaint against Hamas, which has governed Gaza since winning its parliamentary election in 2006.

On Nov. 1, fighting resumed when Israel destroyed part of another tunnel. During the raid, five Israeli soldiers were injured in a clash with Hamas’ armed wing, Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, four of whose members were killed in the encounter.

Israel hoped to curb such incidents in launching Operation Pillar of Defence, its biggest military campaign in three years. It came on the heels of Operation Cast Lead, which unfolded over a three-week period from December 2008 to January 2009. During Cast Lead, Israel pummelled Gaza by land, air and sea, leaving parts of Gaza in smouldering ruins.

With Cast Lead, Israel not only won a respite from war, but reestablished its deterrent power. Yet as widely expected, the truce that ended Cast Lead did not endure for long. In 2010, Palestinian factions in Gaza more or less hewed to it, firing few rockets and mortars and attempting even fewer cross-border penetrations.

In 2011 and 2012, however, the Palestinians fired 680 and 790 rockets at Israel, fanning speculation that yet another round of fighting was in the offing.

Israel responded with retaliatory strikes, but they did not deter the Palestinians, who blamed Israel for the escalation in violence. Then, as now, Palestinians demanded an end to Israel’s naval blockade of Gaza and a complete Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank.

Israel unilaterally pulled out of Gaza in 2005, hoping the Palestinians would focus on nation-building. Instead, Hamas concentrated on building its military capabilities, with Iran assisting Hamas.

The Israeli government imposed the siege after Hamas, the Islamic Resistance Movement, seized control of Gaza from the mainstream Fatah faction in the summer of 2007, thereby splintering the Palestinian national movement into two irreconcilable camps. Hamas, unlike Fatah, has never accepted Israel’s existence. Its charter calls for Israel’s destruction and the establishment of an Islamic Palestinian state in its place.

From 2005 to 2008, the situation in the Gaza border region deteriorated as Israel and various Palestinian armed groups traded fire. Occasionally, for tactical reasons, Hamas reined in more radical organizations like Islamic Jihad. But in general, Israel’s border with Gaza burned with intensity.

In October 2012, the Palestinians launched 92 separate attacks on Israel, confirming fears that a war was imminent. Israel’s patience snapped on Nov. 14, a day after 100 rockets fell on Israel within a 24-hour period and just days after an anti-tank missile hit an Israeli army jeep on a routine patrol along the frontier.

Operation Pillar of Defence began with Israel’s assassination of Hamas’ top commander, Ahmed Jabari. In the ensuing days, Israel struck more than 1,000 targets, principally rocket launch pads, weapons depots and Hamas government buildings. One hundred and thirty three Palestinians, including 79 fighters, were killed.

The Palestinians fired 1,500 rockets and mortars at Israel, hitting such cities as Beersheva, Rishon LeZion, Ashdod and Ashkelon and killing six Israelis, including two soldiers. Israel’s Iron Dome defence system intercepted more than 400 Palestinian rockets, a remarkable technological achievement.

For the first time, several long-range Palestinian rockets reached Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Although the rockets landed harmlessly off Tel Aviv’s coast and in Jerusalem’s outskirts, Israeli officials expressed concern over the Palestinians’ ability to develop such missiles.

Last July, Israeli Chief of Staff Benny Gantz elaborated on this point, saying that Hamas has produced locally-manufactured M-75 rockets, which are based on Iranian technology and are capable of reaching Israel’s heartland.

Operation Pillar of Defence ended with a ceasefire, hammered out on Nov. 21 by the then U.S. secretary of state, Hillary Clinton, and the then Egyptian foreign minister, Mohammed Amr.

The Palestinians exacted two minor concessions from Israel. Gaza’s fishing zone was extended from three to six nautical miles, while Gaza farmers were permitted to work lands closer to Israel’s border security fence.

This past September, on the eve of the first anniversary of Operation Pillar of Defence, Israel removed many of the remaining restrictions on the import of building materials into Gaza. Israel banned such imports after Hamas’ takeover of Gaza, rightly fearing they would be used for military purposes.

Egypt has played a leading role in trying to stabilize the border region, having closed some 500 smuggling tunnels in recent months. By the same token, Hamas has increased its capacity to build weapons like rockets and mortars.

Since the advent of Operation Pillar of Defence, Hamas has been weakened by two developments: the ouster of Egypt’s president, Mohamed Morsi, who was a keen supporter, and the cooling of bilateral relations with Iran. The Iranians slashed their annual subsidy to Hamas after it vacated its headquarters in Syria, Iran’s ally.

Yet Hamas remains remarkably resilient and utterly committed to the armed struggle against Israel, its arch enemy. Israel’s border with Gaza will likely continue to be a flashpoint in the months and years ahead.