Three decades on, Israel’s historic peace treaty with Jordan remains fundamentally intact, though it has been buffeted and damaged by a series of events from almost the outset.

Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan formally entered into a state of peace on October 26, 1994 in a ceremony in the southern Negev Desert brimming with pomp and circumstance. Signed about a year after the launch of Israel’s Oslo peace process with the Palestinians, it was Israel’s second peace treaty with an Arab country, following its path-breaking agreement with Egypt in 1979.

Israel’s treaty with Jordan has endured a succession of crises and still stands despite being maligned and condemned by Islamists, nationalists and ethnic Palestinians.

Last November, in a tangible and typical sign of its differences with Israel, Jordan recalled its ambassador in Tel Aviv in protest over the “humanitarian catastrophe” in the Gaza Strip. This was a reference to the high Palestinian death toll in the Israel-Hamas war, which was ignited last October 7 after Hamas terrorists killed roughly 1,200 civilians and soldiers and kidnapped 251 Israelis and foreign nationals in southern Israel.

After withdrawing its envoy, Jordan let it be known that normal diplomatic relations with Israel would not be resumed until the war winds down.

This past August, following Israel’s assassination of Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh in Tehran, Jordanian Foreign Minister Ayman Safadi, a persistent critic of Israel, lambasted Israel as a “rogue” state.

But for all its disagreements with its Jewish neighbor, Jordan and Israel have close security relations. Last April, Jordan played an active role in Israel’s defence when it downed a barrage of drones and rockets over its territory fired by Iran toward Israel. The Jordanian government, acutely aware of the anti-Israel demonstrations that have taken place in front of the Israeli embassy in Amman since the outbreak of the war, described its military reaction as an act of self-defence.

Jordan’s response to Iran’s ballistic missile attack against Israel on October 1 unfolded in exactly the same manner, underscoring the shared interests it shares with Israel in spite of its sharp critique of Israel’s policy toward the Palestinians in the West Bank.

Over Jordan’s objections, Israel rejects a two-state solution to resolve the Palestinian problem and continues to expand its burgeoning network of settlements in the West Bank.

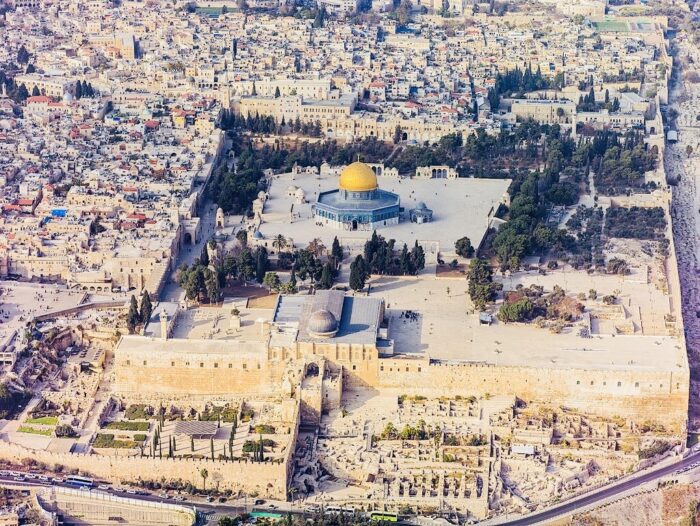

Apart from these key issues, Jordan has accused Israel of tampering with the status quo at the Temple Mount complex in eastern Jerusalem, the third holiest site in Islam and the holiest site in Judaism. Since the 1967 Six Day War, Jordan has been the custodian of the Temple Mount, known as the Haram al-Sharif in Arabic, while Israel has been in charge of overall security.

Jews are officially allowed to visit the Temple Mount, but are forbidden to pray there. Right-wing Israeli nationalists generally regard this formula as an affront, and this has triggered periods of tension between Jews and Palestinians, on the one hand, and Israel and Jordan, on the other hand.

The volatility of this issue is such that, in 2021, Jordan denied Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu permission to fly over Jordanian air space en route to the United Arab Emirates in retaliation for Israel’s refusal to permit Jordan’s crown prince to pray at the Al-Aqsa Mosque on the Temple Mount.

This incident illustrates the mercurial nature of Israel’s relationship with Jordan, which geographically was once part of Palestine. Britain created Trans-Jordan in the 1920s to suit its imperial interests in the Middle East. Eventually, Trans-Jordan changed its name to Jordan.

Opposed to a Jewish state, Jordan joined the Arab war against Israel in 1948, conquering the West Bank and East Jerusalem. In 1963, King Hussein established a secret channel of communication with Israel. But just four years later, Israel captured the West Bank after Jordan shelled Israel’s capital in western Jerusalem.

By 1970, the Palestine Liberation Organization had created a state-within-a-state in Jordan, from whose territory the Palestinians attacked Israel. These raids and bombardments exposed Jordan to Israeli reprisals. In a showdown, King Hussein drove the PLO out of Jordan, stabilizing Jordan’s borders with Israel. At the behest of the United States, Israel propped up Jordan by repelling an invasion from Syria.

On the eve of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, King Hussein personally warned Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir that Egypt and Syria intended to wage war to recapture the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Yet, in solidarity with the Arab world, Jordan sent an armored force to the Golan to fight alongside Syria.

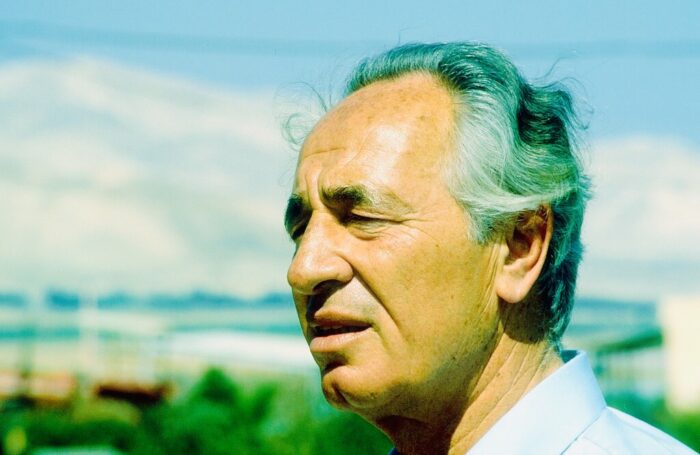

During the postwar period, King Hussein tried vain to settle Jordan’s dispute with Israel over the future of the West Bank and Gaza. In 1987, he and Shimon Peres, the then Israeli foreign minister, signed an accord calling for a Middle East peace conference, but it was scuttled by Israel’s hardline prime minister, Yitzhak Shamir. Shortly afterward, Jordan abandoned its claim to the West Bank.

With Israel and the PLO having forged a rapprochement in 1993 under the first Oslo peace accord, King Hussein was finally prepared to recognize Israel. Many of his Palestinian subjects, the descendants of refugees who had fled or were driven out of Israel, were bitterly against his plan.

Although they comprise about two-thirds of Jordan’s population, the king was undeterred by their opposition. He wanted to avoid another war with Israel, which shares its longest border with Jordan. And he sought to bury the “Jordan-is-Palestine” slogan, which was backed by right-wingers in Israel who did not wish to see the emergence of a sovereign Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza.

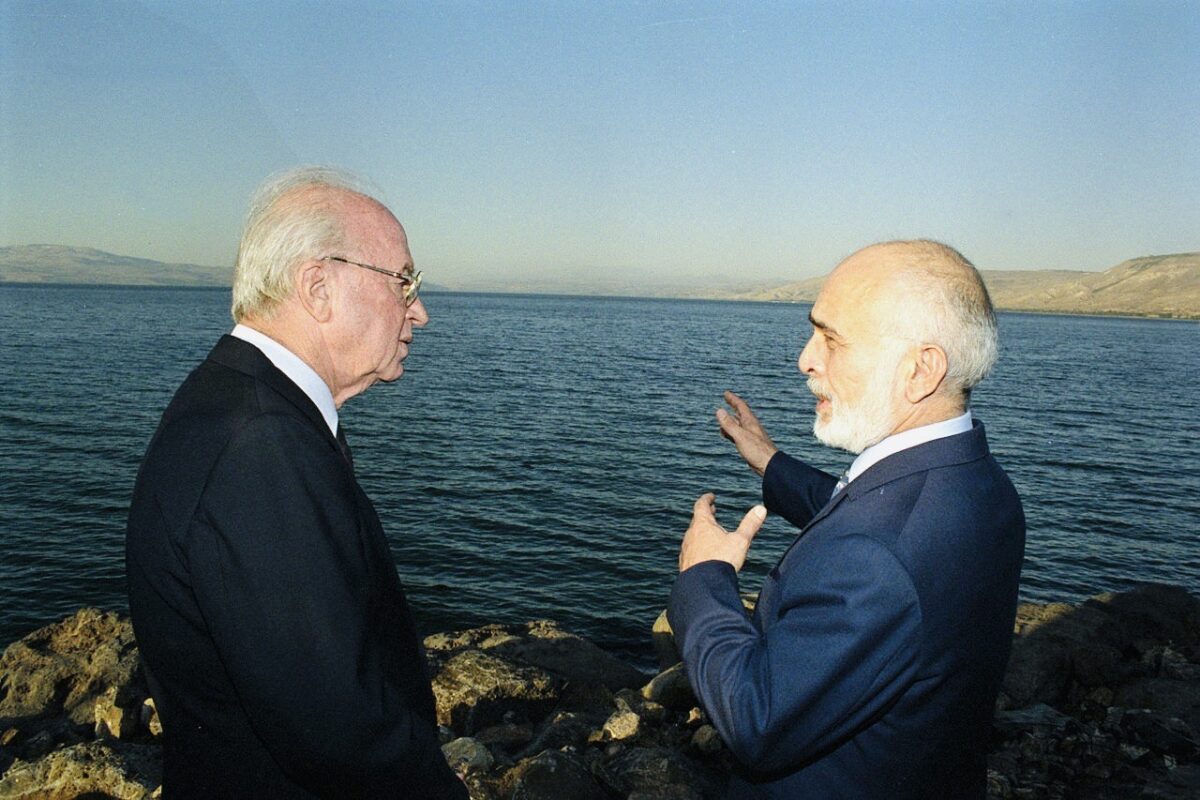

By then, King Hussein and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin had formed warm personal relations.

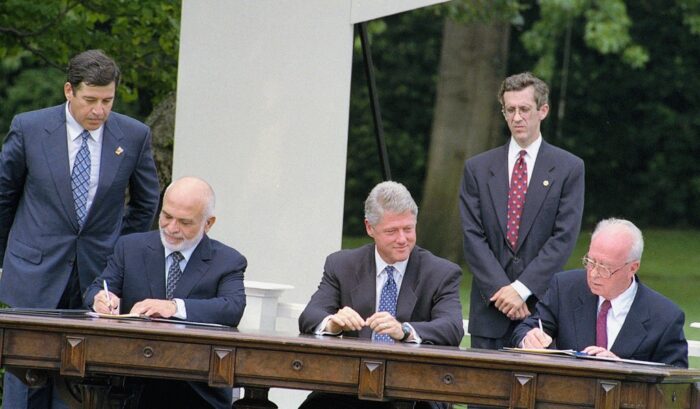

On July 25, 1994 Israel and Jordan signed the Washington Declaration, a non-belligerency pact. Three months later, at a border crossing near the Israeli port of Eilat, Israel and Jordan signed and sealed a peace treaty, which was fleshed out by 15 bilateral agreements.

“This is a peace with dignity,” King Hussein said of the treaty. “This is a peace with commitment. It will not be simply a piece of paper.”

As stipulated in the treaty, Israel ceded about 300 square kilometers of disputed land, mostly in the Arava desert, to Jordan. As well, Israel promised to deliver 50 million cubic meters of potable water to Jordan every year and accepted Jordan’s role as the guardian of Islamic and Christian holy places in Jerusalem. Both countries also reached an understanding to jointly combat terrorism.

The United States forgave Jordan’s $700-million debt and was instrumental in the formation of the Qualified Industrial Zones in Jordan, where goods are manufactured with Israeli components and exported to the U.S. free of tariffs and quotas. QIZs have generated 20,000 jobs, bolstered exports and, in the eyes of some Jordanians, have validated the treaty.

Rabin’s assassination in 1995 was an enormous blow to King Hussein, who considered him a real partner. At his funeral in Jerusalem, he called him a “brother” and a “friend.”

King Hussein’s relationships with Rabin’s successors, Peres and Netanyahu, were problematic. He accused Peres of using disproportionate force and killing civilians in Operation Grapes of Wrath, a 16-day military campaign in Lebanon in 1996 designed to weaken Hezbollah.

And he was miffed that Netanyahu had not consulted him before ordering the opening of an archeological tunnel near the Temple Mount, an event that caused widespread rioting and bloodshed. King Hussein, too, was angered by Netanyahu’s announcement, in 1997, that he intended to build a residential district in Har Homa in East Jerusalem.

For King Hussein, the last straw was the Khaled Mashaal affair in the same year. Mossad agents, carrying Canadian passports, attempted to assassinate Mashaal, a senior Hamas official, in Amman. This caused a diplomatic crisis that almost drove Jordan to sever ties and security cooperation with Israel.

Due to intense Jordanian pressure, Israel was compelled to provide the antidote to save Mashaal’s life and to agree to release Hamas’ founder, Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, from an Israeli prison in exchange for Jordan’s release of the captured Mossad operatives.

Tensions rose again when a Jordanian soldier killed a group of Israeli students visiting the Island of Peace, land leased by Jordan to Israel near the Sea of Galilee under the terms of the treaty. In a stunning gesture of remorse, King Hussein knelt before the victims’ families in Israel.

Despite his act of atonement, anti-Israel sentiment was building in Jordan, underscoring the perception that the treaty is widely unpopular and is essentially a government-to-government project.

An anti-normalization campaign, spearheaded by Islamists, professionals and leftists who oppose all ties with Israel, has sprung up in Jordan. Some of these Jordanians have urged the government to abrogate the treaty altogether.

With the death of King Hussein in 1999 and the ascension of his son, Abdullah II, as his successor, Israel’s ties with Jordan were subjected to further turbulence. King Abdullah, who is married to a Palestinian, is not as favorably disposed toward Israel as his late father, and has visited Israel only once. In his 2011 autobiography, he claims that “Israeli policies are mainly to blame for (the current) gloomy reality.”

Tensions soared yet again with the eruption of the second Palestinian uprising in September 2000. Israel’s crackdown on Palestinian terrorism, combined with its decision to build a separation barrier along and inside the West Bank, elicited a strong Jordanian response. Jordan recalled its ambassador. Diplomatic relations were not fully restored until 2005, when the revolt petered out.

Jordan once again withdrew its ambassador following the outbreak of the second cross-border Gaza war in 2014.

In spite of these setbacks, Israel-Jordan relations have flourished in certain areas.

Israel, an innovator in desalination technology, has doubled its water allocation to Jordan. Three years ago, Israel and Jordan agreed to a water-for-energy deal in which Israel will provide Jordan with 200 million cubic meters of water in exchange for solar energy.

And after discovering natural gas off its coast in 2014, Israel agreed to export $500 million worth of gas to Jordan.

However, Israel’s strained ties with Jordan derailed a water conveyance project linking the Red Sea to the Dead Sea, which was projected to supply electricity and desalinated water to both sides.

Jordan did not take kindly to U.S. and Israeli policies during Donald Trump’s presidency. Jordan warned the United States that moving its embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem would be a “red line” that would have a “catastrophic” impact. Jordan blasted Israel after Netanyahu said he was prepared to annex the Jordan Valley in the West Bank.

Israel tried to improve bilateral relations with Jordan after Netanyahu temporarily left office in 2021.

His successor, Naftali Bennett, who claimed that Netanyahu had “destroyed” Israel’s relations with Jordan, visited Amman and declared that his government was “fixing the relationship.”

The then Israeli foreign minister and prime minister-to-be, Yair Lapid, described Jordan as “an important strategic ally for Israel” and pledged to “strengthen the relationship between our two countries.”

In a phone call with King Abdullah, Israeli President Isaac Herzog underlined the importance of working toward a “just and comprehensive” peace on the basis of a two-state solution.

Israel’s relations with Jordan improved during the Bennett/Lapid interregnum, but Jordanian rhetoric toward Israel remained fairly harsh.

Jordan reacted cooly to the 2020 Abraham Accords, during which four Arab states — Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco and Sudan — pledged to normalize relations with Israel. Indeed, Jordan declined to send a diplomatic representative to the White House ceremony marking the Abraham Accords.

Jordan’s attitude was summed up by Safadi: “If Israel considers the (Abraham Accords) as a means to end the occupation and meet the Palestinians’ rights to freedom and the creation of a viable independent state with East Jerusalem as its capital on the pre-1967 borders, the region will move ahead towards realizing peace. Otherwise, Israel will deepen the conflict, which will jeopardize the entire region’s security.”

Jordan, in 2022, boycotted the Negev Summit, a diplomatic venue held in Israel to formalize Israel’s collaboration with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco and Egypt across a range of fields. Jordan’s explanation for boycotting this forum was the absence of Palestinian participation. According to reports, King Abdullah did not want to be seen as an Israeli “collaborator.”

After 30 years, Israel’s peace treaty with Jordan remains in place, a pillar of regional stability, despite trials and tribulations. Much like the Israel-Egypt peace treaty, it is bereft of warmth and popular support. But its strategic importance to both Israel and Jordan should not be underestimated.