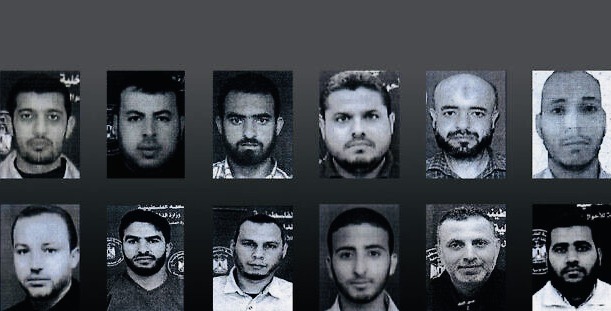

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency is clearly an organization under sharp scrutiny after Israel presented donor nations with evidence that twelve of its employees participated in Hamas’ deadly attacks against Israel on October 7, and that ten percent of its staff, or 1,200 individuals, are members of Hamas or Islamic Jihad.

As a result of this extremely serious accusation, nine employees have been fired (two have since died and one is being investigated), and more than a dozen countries have temporarily suspended funding to UNRWA pending an investigation by the United Nations’ auditing body, the Office of Internal Oversight Services, which is expected to release a report later this month or in March.

Founded in 1948 after Israel’s birth and the dispossession of 700,000 Palestinians from their homes in what is now Israel, UNRWA initially provided a wide range of social, medical, nutritional and educational services to both Palestinian refugees and Jewish immigrants in Israel.

Israel assumed sole responsibility for Jewish newcomers after 1952, leaving UNRWA with the task of caring for several million displaced Palestinians in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Today, 80 percent of Palestinians in Gaza are reliant on foreign aid, which is distributed by UNRWA.

Seventy five years after its creation, the United States, Japan and Germany are its biggest donors. In 2022, the United States funded UNRWA to the tune of $344 million. Countries like Canada, Britain, France and Australia provided additional financial support.

From almost the very beginning, UNRWA has been accused of deliberately perpetuating the Palestinian refugee problem, which lies at the heart of Israel’s protracted conflict with the Palestinians.

In the wake of the first Arab-Israeli war, Israel refused to allow Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, fearing they would be disloyal and pose a security threat to the state. Nonetheless, Palestinians called for a “right of return,” a demand endorsed by Arab and Muslim states.

The majority of Palestinian refugees and their descendants never accepted Israel’s existence and legitimacy and continued to languish in refugee camps throughout the Middle East, embittered by their displacement and the refusal of host nations, namely Lebanon and Syria, to give them citizenship.

Arab states ranging from Egypt to Iraq encouraged Palestinian grievances against Israel and its Western allies, made no real attempt to integrate them into their societies, and fought wars with Israel on behalf of the Palestinians.

UNRWA schools hewed to the Palestinian narrative that Israel was an illegitimate colonial settler state responsible for the nakba, the disaster that befell the Palestinians in 1948.

The 160,000 Palestinian Arabs who remained in Israel were granted citizenship and civic rights, though most of their lands were appropriated. Until 1966, they lived under military rule as second-class citizens.

Not surprisingly, Israel has had a rocky relationship with UNRWA, regarding it as an enabler of Palestinian rejectionism and terrorism and arguing that it should be dismantled.

Last week, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu alluded to these concerns when he said, “The time has come for the international community and the United Nations itself to understand that UNRWA’s mission must be ended. UNRWA is perpetuating itself. It seeks to preserve the issue of Palestinian refugees.”

According to the dossier Israel handed to UNRWA donor states, seven of its employees who assisted Hamas on October 7 were teachers, two others worked in schools in other jobs, and the rest were said to be a clerk, a storeroom manager and a social worker.

The United Nations has condemned UNRWA workers who were complicit in Hamas’ massacre almost four months ago. But as Martin Griffiths, the UN’s top humanitarian official, told the UN Security Council, the “alleged actions of a few individuals” should neither tarnish the reputation of an organization with 13,000 employees in Gaza nor leave it open to insolvency.

Philippe Lazzarini, UNRWA’s commissioner-general, wrote in a tweet, “Our humanitarian operation, on which two million people depend as a lifeline in Gaza, is collapsing. I am shocked such decisions are taken based on alleged behavior of a few individuals and as the war continues, needs are deepening and famine looms. Palestinians in Gaza did not need this additional collective punishment. This stains all of us.”

And in a joint statement, UNICEF, the World Health Organization and the World Food Program warned that a pause in finding UNRWA would have “catastrophic consequences” on Gaza’s 2.3 million Palestinians.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has implored major donors to reconsider their suspension of contributions to UNRWA.

It seems clear that donors like the United States, which cut off funds to UNRW during Donald Trump’s presidency, consider the current pause as temporary.

As Linda Thomas-Greenfield, the U.S. ambassador to the UN, said the other day, “We know that this agency provides lifesaving services under incredibly challenging circumstances in Gaza and it contributes to regional stability and security. For this reason, and for the sake of millions of Palestinian civilians who depend on UNRWA’s services, it is vital that the UN take quick and decisive action to hold accountable anyone guilty of heinous actions and to strengthen oversight of UNRWA’s operations and begin to restore donor confidence.”

It remains to be seen whether UNRWA can be sufficiently reformed, but in the meantime it provides urgent humanitarian services in Gaza.

Absent UNRWA, the Israeli army would be legally and morally responsible for distributing aid to Palestinians, a task that would hamper its current ground offensive in Gaza.

The Israeli government believes that other UN agencies, principally the High Commissioner for Refugees, could supplant UNRWA, but that is a debatable claim.

In the meantime, 85 percent of Gazans depend on UNRWA for sheer survival.