Twenty years ago today, Israel withdrew unilaterally from its self-declared security zone in southern Lebanon, ending a lengthy occupation that the then Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, described as a “tragedy.”

Under cover of darkness, Israeli armored personnel carriers, trucks, jeeps and tanks rolled into Israel, accompanied by several thousand troops from the South Lebanon Army, a Lebanese militia financed and supported by the Israeli government.

The vacuum was filled by the Lebanese army and Hezbollah, a pro-Iranian Lebanese Shi’a organization which fought a guerrilla war with Israel following its invasion of Lebanon in June 1982.

The majority of Israelis backed the pullout, fed up with a grinding conflict that claimed the lives of 256 Israeli soldiers from 1985 until 2000.

Two decades on, Hezbollah, under the leadership of Hassan Nasrallah, has morphed into Israel’s deadliest enemy after Iran. Hezbollah has locked horns with Israel in a succession of skirmishes and in one war in 2006.

Hezbollah, in violation of a United Nations ceasefire that ended that month-long war, operates along the Lebanese border. In 2018, the Israeli army detected and destroyed several tunnels that Hezbollah intended to use during an offensive in the event of another war with Israel.

Hezbollah has also established itself in southern Syria, close to the Golan Heights, which Israel captured from the Syrians in the 1967 Six Day War and annexed in 1981, when Menachem Begin was prime minister. Last year, the United States formally recognized Israel’s sovereignty over the Golan.

In recent years, the Israeli Air Force has bombed Hezbollah weapons convoys en route from Syria to Lebanon, while Israel has warned the Lebanese government that attempts by Hezbollah and Iran to build precision-guided missile factories on Lebanese soil will be regarded as a strategic threat to its security and will not be tolerated.

Hezbollah, with a battle-hardened army and 130,000 to 150,000 missiles in its arsenal, is an adversary that Israel regards with the utmost seriousness. But at this point in time, neither Israel nor Hezbollah desires a war, which would be costly to both sides in terms of casualties and property damage.

Israel’s military adventure in Lebanon — a nation of feuding Muslim and Christian sects which won its independence from France — began shortly after the Six Day War.

Palestinian guerrilla forces controlled by the Palestine Liberation Organization established a presence in southern Lebanon, a development that the weak central government was powerless to stop. Starting in 1968, the Israeli armed forces launched the first of numerous retaliatory raids into Lebanon in response to Palestinian incursions into Israel.

In December of that year, in retaliation for a Palestinian attack on an El Al airliner in Athens, an Israeli commando force struck Beirut’s international airport, blowing up 14 passenger and cargo planes on the tarmac belonging to Lebanese and Middle Eastern airlines.

The raid did not have a lasting effect. Lebanon, which had been Israel’s least hostile Arab neighbor, turned into a battleground as Israeli and Palestinian forces repeatedly clashed.

In 1977, two years after the civil war in Lebanon broke out, the Israeli government established a Good Fence policy, allowing Lebanese civilians to cross the border and work and shop in Israel.

Reacting to the coastal road massacre, a Palestinian terrorist attack in March 1978 which resulted in the deaths of 38 Israelis, Israel launched Operation Litani, its biggest thrust into Lebanon since the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. Israeli troops, welcomed in some Shi’a villages as saviors who would purge their land of Palestinian guerrillas, battered PLO bases and pushed as far north as the Litani River.

The fighting was a brought to a halt by United Nations Security Council Resolution 425, which, among other things, created the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon, a peacekeeping force composed of several thousand soldiers from different nations. UNIFIL, however, was unsuccessful in bottling up the PLO, which continued attacking northern Israel.

On June 6, 1982, following a year of escalating border tension, Israel invaded Lebanon and advanced as far as the capital, Beirut. Israel succeeded in driving the PLO out of Lebanon, but the void was gradually filled by two new Shi’a militias, Amal and Hezbollah, which was supported by Iran and Syria.

In short order, Israel created a security zone in the far south, a 400 square mile enclave comprising about 10 percent of Lebanon’s land mass and inhabited by 150,000 Lebanese in more than 60 villages and towns. Israel’s surrogate there, the South Lebanon Army, was commanded by Saad Haddad, who had been a major in the Lebanese army. After Haddad’s death, Antoine Lahad, another veteran of Lebanon’s army, stepped into his shoes.

From that point forward, the Israeli army and the South Lebanon Army cooperated in fighting Hezbollah, a resourceful and determined enemy whose roadside bombings, ambushes and suicide attacks exacted mounting casualties.

Israel inflicted pain on Hezbollah. In 1992, an Israeli helicopter gunship fired a missile at a car carrying Hezbollah’s leader, Abbas Musawi, killing him and his family. Hezbollah responded harshly, bombing the Israeli embassy in Buenos Aires and accelerating its campaign of hit-and-run attacks in southern Lebanon. In one of these assaults, Hezbollah killed an Israeli general.

On average, 20 to 25 Israeli soldiers were killed in Lebanon every year, though the death toll fell to 11 in 1999.

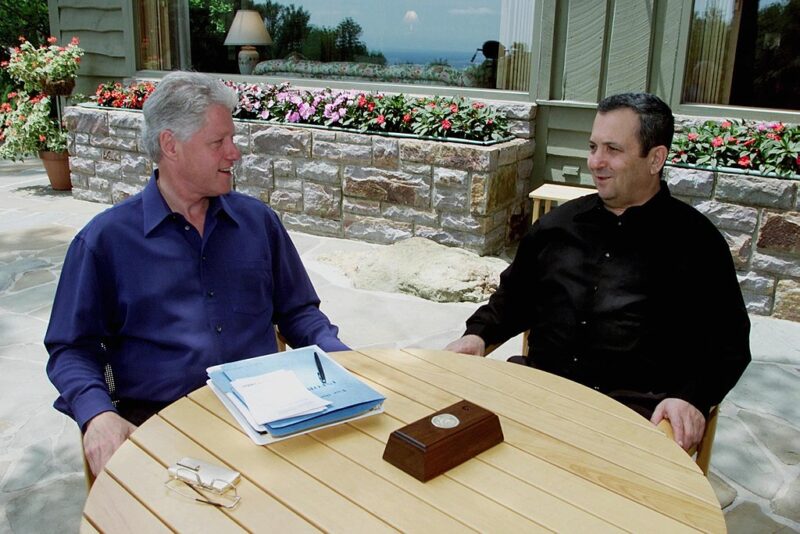

Israel’s new prime minister, Ehud Barak, announced he would withdraw from Lebanon, preferably as part of a peace treaty with Syria. Israel and Syria had been conducting direct talks, but they failed, and Barak decided that Israel’s best option would be a unilateral withdrawal from Lebanon.

Israel’s pullout emboldened the Palestinians and was a contributory cause of the second Palestinian uprising, which erupted in September 2000.

Within months of Israel’s withdrawal, Hezbollah abducted three Israeli soldiers patrolling the border with Lebanon, killing all of them. For the next few years, tensions rose and subsided.

In the summer of 2006, Hezbollah kidnapped two Israeli soldiers on a patrol road adjacent to the border. Israel responded with a reprisal raid, after which the Israeli prime minister, Ehud Olmert, ordered an invasion of Lebanon. During the course of the war, Hezbollah fired 4,000 rockets at Israel, damaged an Israeli naval vessel, killed 165 Israeli soldiers and civilians and all but paralyzed the Galilee. Israel wreaked devastation on Lebanon, but the war ended inconclusively.

Fourteen years on, Hezbollah is stronger than ever militarily and continues to ignore United Nations resolution 1701, which calls for the disarmament of all non-governmental militias.

Two decades ago, Israel made the correct decision to withdraw from Lebanon, which had degenerated into a quagmire for the Israeli army. But Israel’s problems with Lebanon, and particularly with Hezbollah, are very far from resolved.

No one will be surprised if Israel and Hezbollah are drawn into another war.