I had the privilege of knowing Joseph Baruch (J.B.) Salsberg, who was already a legendary figure when I met him in the autumn of 1974.

I was a reporter on The Canadian Jewish News and he was one of its freelance columnists. Salsberg, tall, irrepressible, witty and always nattily dressed, would usually arrive at the office before noon and submit his weekly column to the editor, Ralph Hyman, a former Globe and Mail reporter.

After conversing with Hyman, whom he had known for decades, he would pop into the editorial room and chat with the staff. Salsberg loved to reminisce, and I always listened attentively. Once, I invited him to my home for dinner and, as usual, he regaled everyone with his fount of knowledge and special brand of Yiddish-inflected humour.

He sure was a talker.

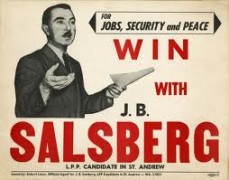

A politician in his heyday, Salsberg was more than just a schmoozer. He was a man of ideas and an activist whose loftiest ambition was to improve society. A trade unionist and a high-ranking functionary of the Communist party in Canada until he fell out with communism, he was also a Toronto city alderman for Ward 4 and a member of parliament for the St. Andrew riding in the Ontario legislature.

Gerald Tulchinsky, a distinguished historian, never had the pleasure of meeting him, but he has nonetheless written a first-class biography of Salsberg.

Joe Salsberg: A Life of Commitment, published by the University of Toronto Press, is a cogent work of impressive scholarship, all the more so because he did not personally know or interview him. In Tulchinsky, Salsberg is blessed to have a biographer who writes more like a journalist than an academic.

Salsberg, whose district encompassed the old Jewish quarter from College to Dundas Streets, would talk to constituents as he leisurely walked down both sides of Spadina Avenue, often making a detour into the Kensington Market. The stroll took him anywhere from three to five hours, but it was a distance that could easily be covered in less than 30 minutes.

“He exuded empathy, told stories and jokes, and extended twinkly-eyed warmth and understanding to people in distress,” Tulchinsky writes. “He was instantly recognizable; a man of above-average height, with auburn hair and moustache, presenting a jovial smile and open face, and an expansive manner, greeting in Yiddish, the language of the immigrant Jews who predominated in the area …”

People reached out to Salsberg, realizing he would try to help anyone in need. Born in a shtetl, he became a cutter in a cap and hat factory at the age of 14 after having dropped out of school. Salsberg was a mensch, a kind and decent human being who believed that the solution to the “Jewish problem” lay in the benefits promised by the advancement of democratic socialism through world revolution.

As Tulchinsky points out, he was mainly interested in the nuts-and-bolts issues of labor mobilization and human welfare legislation, and not necessarily so much in communist ideology.

In Tulchinsky’s judgment, Salsberg was one of the most important Communist labor figures of his generation, and his work as a parliamentarian in promoting progressive labor and human rights legislation was “nothing short of monumental.”

Tulchinsky adds, “He led a life of total commitment to the advancement of the welfare of working people.”

He was born in 1902 in Lagow, a town in Russian-ruled Congress Poland whose Jewish inhabitants were murdered by the Nazis in Treblinka in 1942. He was the first child of Abraham, a baker, and Sarah-Gitel, who came from a family of prosperous horse traders. Abraham, a religious Jew, went to Toronto in 1910, but soon left. Returning to Canada, he worked as a junk collector. His family joined him in Toronto in 1913, when an estimated 11,624 Jews immigrated to Canada.

Quitting school to help his struggling parents, Salsberg landed a job in a leather goods factory, where he became a cutter. Stung by the deplorable conditions in the industry, he joined a union. According to Tulchinsky, he had a penchant for protest and reform and a talent for organization.

Of course, his father was none too pleased by his rejection of Torah Judaism and his drift into left-wing politics. Salsberg, who had flirted with Zionism, joined the Communist party in 1926, saying he sought answers to “disturbing problems” at home and abroad. He was inspired by the new order in the Soviet Union.

Unlike some other Jews drawn to communism, Salsberg never abandoned his Jewish identity. A Jewish cultural nationalist and Yiddishist, he regarded the party as a vehicle for celebrating secular Judaism.

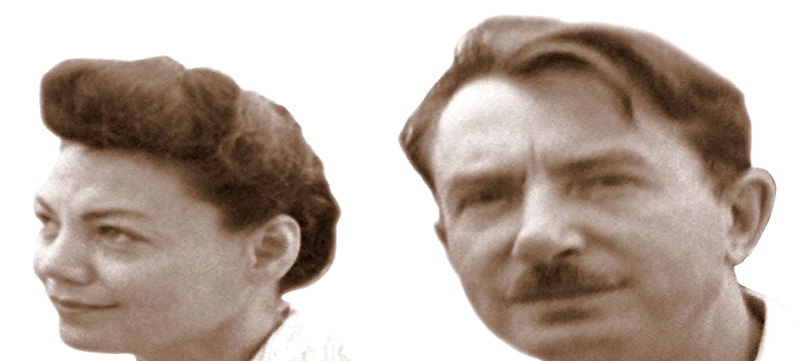

In 1927, he married Dora Wilensky, a university student of Russian descent who would be a powerful influence on him and who would enjoy a successful career in social work in the Jewish Family and Child Services. They were an adoring couple, but their attempts to have children ended in disappointment and tragedy.

A year after his marriage, he was appointed national organizer of the Industrial Union of Needle Trades Workers. The garment industry was highly volatile, with strikes breaking out regularly. Salsberg launched an aggressive campaign to organize cloak makers and dressmakers, first in Montreal and then in Toronto and Winnipeg.

And while he revelled in this activity, his eye was already on local politics. From 1934 to 1937, he attempted in vain to win a seat in Ward 4. He was finally elected to city council in 1938, and was reelected again in the early 1940s.

One of his predecessors, Max Factor, then an MP for Spadina in the House of Commons, campaigned against him, warning voters that his belief in the “subversive doctrine of communism” would not be in their interest. The Toronto Zionist Council lambasted Salsberg, too, saying that the Communist party was “an avowed enemy of our great aspirations in Palestine…”

In succeeding campaigns, the Canadian Jewish Congress and B`nai Brith came out against Salsberg as well. Elected to the Ontario legislature in 1943, Salsberg held the seat until 1955, when he was defeated by Conservative Alan Grossman.

As Tulchinsky points out, Salsberg won in St. Andrew only five days before Fred Rose, a fellow Communist, triumphed in the Montreal federal riding of Cartier.

Focusing on labor and human rights issues, he was particularly interested in cases of discrimination against minorities, who faced bigotry in finding jobs and housing. Salsberg played a key role in pushing through legislation ensuring fair accommodation and employment practices, and he was instrumental in the passage of minimum wage laws. In addition, he fought for the concept of equal pay for equal work for female employees, low-cost housing and day nurseries, and he supported the arts.

Leslie Frost, the premier of Ontario from 1949 to 1961, liked and respected Salsberg and his colleague, Alex MacLeod, and was once heard to say that “those two honorable gentlemen … have more brains than my entire backbench put together.”

Under pressure from the Communist party, Salsberg stood up in the legislature and praised Joseph Stalin, who had just died, as “one of the greatest personalities of our time.”

By this juncture, Salsberg had already voiced serious concerns about the Soviet Union’s attitude toward its Jewish minority. His disillusionment with Soviet-style communism actually emerged in the 1930s, when the party’s Jewish section, Yevsektsiya, was abruptly closed and Jewish cultural life was suppressed.

“So a lot of us began to wonder, what the heck is going on,” Tulchinsky quotes Salsberg as saying.

Unable to raise his misgivings in the Canadian party’s national executive committee, he went to Moscow in the summer of 1939 to seek out an explanation. “He got nothing from his trip, except the opportunity of seeing his family in Poland on his way back to Canada,” writes Tulchinsky.

Safely back in Toronto, Salsberg was excoriated for having had the temerity to address the “Jewish question.” Being a loyal party member, he did not openly criticize Moscow’s non-aggression pact with Berlin in August 1939. And in the late 1940s, he sealed his lips when the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was disbanded and Jewish writers, actors, intellectuals, diplomats and generals were arrested and even executed.

He remained loyal to the party, not wishing to give anti-communists ammunition. In private, though, he lashed out at the Soviet Union’s failings. To many of his fellow communists, Salsberg was regarded as a “right-wing deviationist” who espoused Jewish “nationalist sentiments.”

In 1955, at a meeting of the national executive committee, he accused the Soviet leadership of overt antisemitism. He based his comments, in part, on a disheartening conversation he had had with two of the country’s leaders, Nikita Khrushchev and Mikhail Suslov, two years before. Incredibly enough, they had denied that antisemitism existed in the Soviet Union. Salsberg, having been expelled from the party and then reinstated, was ousted from its national executive committee in 1956.

“It is not entirely clear whether Salsberg jumped or was pushed,” Tulchinsky writes. “The Jewish question had broken Salsberg’s faith.”

On May 16, 1957, less than a year after he had supported Israel’s invasion of the Sinai Peninsula in the Suez War, he resigned his party membership, explaining that “historic changes in the world and in Canada demand new thinking and new alignments for progress and for a democratic socialist future.”

Speculating why Salsberg remained loyal to the party for so long, Tulchinsky says, “He was not stupid, naive, blind or uninformed. He was, like many prominent historical figures, a flawed man… Salsberg, like so many others in the movement, was prepared to accept the imperfections, even evidence of the Stalinist atrocities, because he believed in the achievability of the ultimate goal of social justice through communism and saw no viable alternative.”

After his break with the party, Salsberg sold insurance and earned a decent living doing so. He did not remarry after his beloved wife’s death in 1959. Along with a few dozen of his former comrades, he formed the New Fraternal Jewish Association and accepted an invitation to write for The Canadian Jewish News. In some of his columns, he slammed the antisemitic and anti-Israel policies of the Soviet Union and its satellite states in eastern Europe.

On the 70th anniversary of the Bolshevik revolution, he wrote that it had been a “tragic and lamentable failure.” In a reference to Stalin, he noted that the revolution had led not to democratic socialism but to the “dictatorship of one person.”

Although he had turned his back on communism, some Jews in Toronto never forgave him his “sins,” especially his support of Stalinism, Tulchinsky observes.

Salsberg died on Feb. 8, 1998 and was buried next to his wife. At his funeral, the Canadian historian Irving Abella said, “Joe’s legacy is profound. It is us. It is a vigorous, committed, confident Jewish community. It is the open, tolerant, humane, decent Canadian society for which Joe and his companions struggled so fearlessly.”

So true.