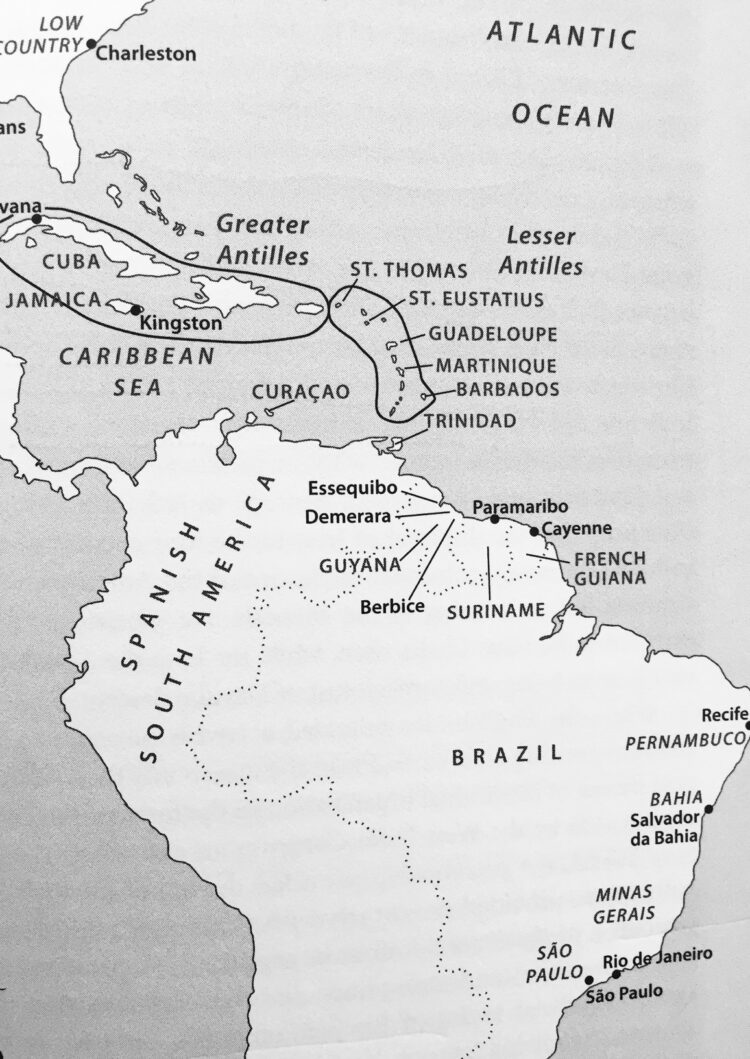

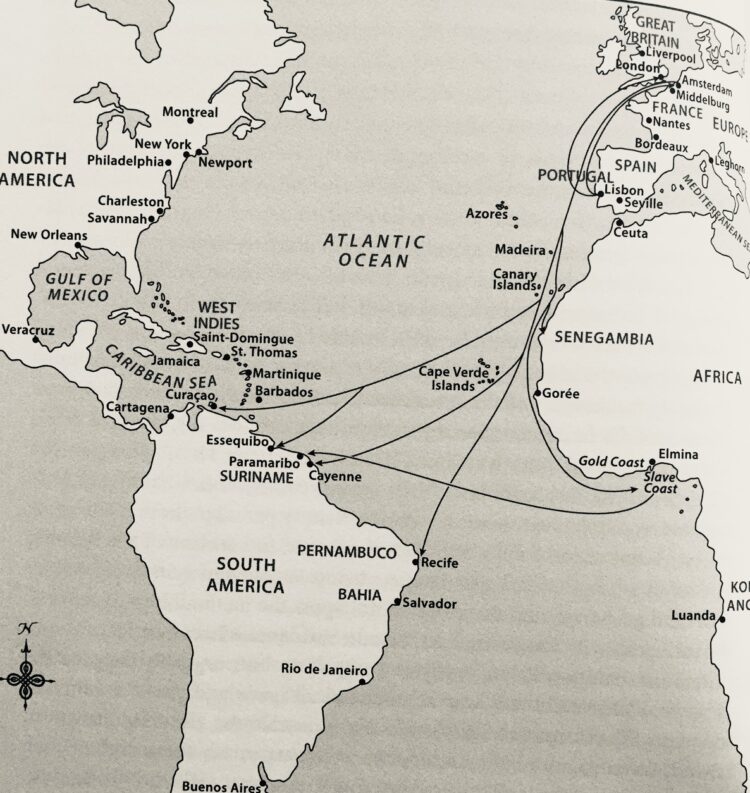

Suriname, a Dutch colony from 1667 to 1975, borders the Atlantic Ocean to the north and is bounded by French Guiana to the east, English-speaking Guyana to the west and Brazil to the south. The size of the U.S. state of Georgia, this fertile tropical outpost produced sugar, coffee, cacao, cotton and hardwood lumber during the colonial period. These crops were planted, cultivated, harvested and processed by African slaves, who were forcibly transported to the Americas from what is today Ghana, Benin, Togo, Nigeria, Angola and Cameroon.

Ninety percent of Suriname’s population consisted of Africans. Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews comprised up to two-thirds of its white residents, some of whom were planters and slave owners.

In Jewish Autonomy In A Slave Society: Suriname in the Atlantic World, 1651-1825 (University of Pennsylvania Press), the historian Aviva Ben-Ur comprehensively examines the status of Jews in this remote South American colony, much of which is covered by dense jungles and bisected by mighty rivers.

The numerically largest group of Jews to settle in Suriname were Portuguese, many of whom hailed from New Christian families that had been compelled to convert to Roman Catholicism. These settlers embraced their Jewish roots after sojourns in Amsterdam and London.

They were followed to Suriname by Ashkenazim, who began arriving in the late 17th century. The majority were petty traders and merchants who resided in the capital, Paramaribo.

By the late 18th century, Suriname was home to some 1,400 Jews. As whites, they were privy to privileges denied to Jews in Europe. “Eager to retain and increase the white population, colonial authorities extended to Jews a territorial and communal autonomy unparalleled in the Jewish Diaspora of the time,” writes Ben-Ur, a professor of Judaic and Near Eastern Studies at the University of Massachusetts. “The confidence and insistence with which Jews continually and largely successfully negotiated the safeguarding and expansion of the favors and exceptions they enjoyed … speak to the central role of Jews in the colony both as whites and planters.”

According to Ben-Ur, the Jews of Suriname were civically better off than their coreligionists in Holland, where they were collectively excluded from guilds, industry, agriculture, shipping and the military.

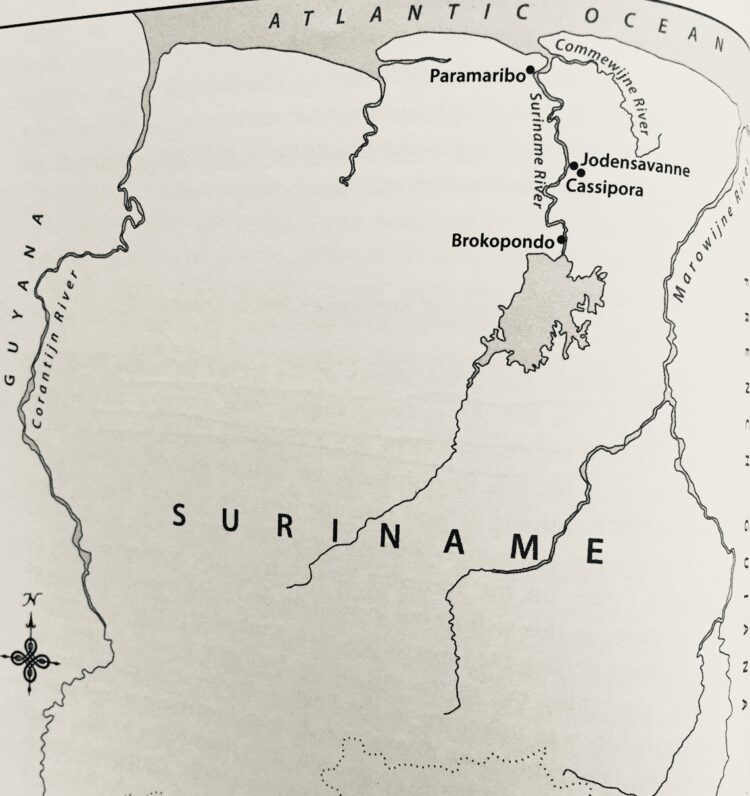

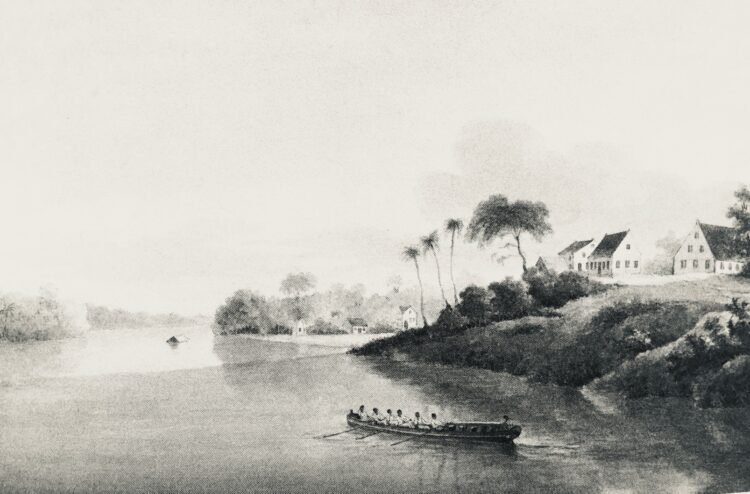

Wielding a remarkable degree of self-rule, Jews were the founders of Jodensavanne, a hillside village on the banks of the Suriname River that adjoined a vast rainforest. Founded in 1685, it was established on land donated by the son of one of Suriname’s first Jewish settlers, David Cohen Nassi, who was born in Portugal as a New Christian but who returned to Judaism in Holland. Extremely wealthy, he earned his fortune in the slave trade. Only the governor of Suriname owned more slaves than him.

As Ben-Ur observes, Jodensavanne — a stronghold of Portuguese-Jewish culture and self-determination — clung to a precarious existence, fending off attacks by Indigenous people, rebellious slaves and outlaw Maroons, enslaved Africans who had escaped into the jungle.

And as Ben-Ur adds, most of the permanent inhabitants of Jodensavanne were poor, eking out a bare living as estate servants, low-ranking army functionaries, boat drivers, peddlers, bakers and laundry washers. More often than not, they survived on charitable contributions, donations from relatives, and subsidies from affluent Jews in Paramaribo.

By the 19th century, mixed-race Jews, or mulattoes or coloreds, constituted half of Suriname’s Jewish population, which suffered from a dearth of women.

“The sharp growth of the African population vis-a-vis whites dramatically increased sexual contact between white men (including Jews) and enslaved women,” writes Ben-Ur. “In the early period of colonial rule, rich Jews collectively owned proportionally more slaves than their Christian counterparts. By 1684, 232 Jewish households, comprising 28.6 percent of Suriname’s European-origin population, owned 30.3 percent of the colony’s enslaved Africans. Sexual relationships between European-origin Jews and enslaved women of African origin must have been especially common on Jewish plantations.”

Some of these women converted to Judaism, with the conversion process being regulated by what Ben-Ur describes as rabbinical leaders.

“The tendency of many Surinamese Jewish masters to convert their slaves to Judaism and recognize them as heirs partly resulted from the paucity of white women in the community, infertility among some biologically related white couples, and the predominance of males … Another factor was the non-racial rabbinical approach to conversion …”

The frequency of such unions prompted an American rabbi visiting Suriname in 1954 to write, “A glance at some of these descendants of the early Jewish settlers is enough to make one realize that there has been a good deal of intermarriage with the native population.”

Interestingly enough, as Ben-Ur points out, conversion to Christianity and intermarriage with white Christians remained rare in Suriname. As a result, Surinamese Jews “continued to constitute a community apart from white Christians.”

Ben-Ur’s book, a portrait of a unique Jewish community in the Diaspora, is both substantive and intriguing.